The 2015 Paris Agreement, celebrated nearly a decade ago, represented a pivotal moment in global climate action with countries around the world committing to limit the rise in global temperatures to well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels. Central to this treaty is the stipulation that nearly 200 signatory nations are required to submit and periodically update their emission reduction strategies, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). These contributions, which should be reported every five years, were designed not only to reflect national priorities and policy directions but also to demonstrate collective ambition in light of the urgent need to meet critical climate targets.

However, ten years after the historic agreement, global ambition to meet these targets has significantly waned. A vast majority of countries failed to submit updated NDCs by the February deadline, and many are also poised to miss the upcoming September deadline. To date, only about 50 nations have presented their third iterations of NDCs—initial submissions were due in 2015 and updates were expected in 2020. In the recent climate summit held alongside the United Nations General Assembly, around 50 countries announced lofty new emissions targets, yet many have yet to formally submit their updated NDCs.

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Secure · Tax deductible · Takes 45 Seconds

Even the commitments that have been made do not appear to project a substantial impact on global temperature stabilization. A preliminary analysis conducted by the World Resources Institute indicates that current NDC proposals would curb emissions by merely 2 gigatons—equivalent to just 10 percent of the needed reductions to stay on track for the 2-degree Celsius threshold.

Joeri Rogelj, a climate science and environmental policy professor at Imperial College London, has stated that relative to the ambitions required to uphold the goals set forth in the Paris Agreement, these proposals are largely inadequate.

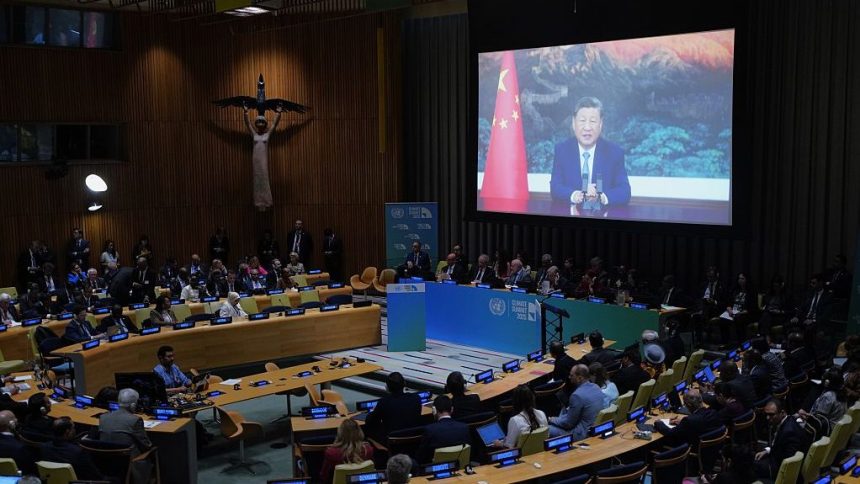

During the recent U.N. summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping declared that China would aim to lessen emissions by 7 to 10 percent by 2035 and intensify its renewable energy deployment by sixfold. As the largest greenhouse gas emitter globally, China’s emissions have recently plateaued. Experts predict this target as one that China can achieve comfortably, given its rapid transition towards renewable energy—though some claim that cutting 30 percent of emissions is both necessary and achievable. However, it is worth noting that China has yet to formally submit an updated NDC.

On another front, historical emitters—the United States and the European Union—arrived at the summit facing questions regarding their climate commitments. The previous administration under President Joe Biden had updated the U.S. NDC, promising significant emission reductions through climate legislation passed with a Democratic majority, aimed at a 66 percent reduction from peak levels by 2035. However, subsequent political shifts have seen the former president, Donald Trump, dismantle much of these commitments, casting doubt on the U.S.’s potential withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and dismissing climate change as a “con job.” During the summit, he advised nations against aligning with what he termed the “green scam,” asserting that their countries would face dire consequences.

Meanwhile, the European Union, long characterized by its ambitious climate goals, has been entangled in its own internal wrangling regarding the level of ambition for its 2035 target, as well as the acceptance of carbon offsets. The EU has made a commitment to submit an updated NDC by COP30—a climate conference scheduled in Belem, Brazil—vowing to aim for somewhere between 66 and 72 percent reduction in emissions by 2035. At the summit, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen also mentioned that efforts are underway to establish a proposed 90 percent emission reduction target by 2040.

Rogelj attributes the EU’s sluggishness in making these commitments to complex negotiations, as the political climate shifts further right within local governance—a trend that often sidesteps environmental priorities. He noted, “As we start to de-carbonize the more manageable sectors, the remaining sectors become increasingly challenging to address. The recent political direction within the EU, with a notable resurgence of right-wing sentiment against environmental initiatives, further complicates negotiations.”

Notably, the EU’s struggle to meet ambitious targets is already influencing global dialogues, as exemplified by the Australian Prime Minister citing the EU’s plans to justify Australia’s own underwhelming climate targets. Cosima Cassel, a program lead at E3G, emphasized that internal disputes concerning the EU’s target undermine its international credibility and stressed the importance of the EU reaffirming its leadership in climate action.

The tepid efforts reflected in current NDC submissions, coupled with the United States’ shifting stance on its climate obligations, have raised valid concerns about the efficacy of the United Nations negotiation process that birthed the Paris Agreement. In the aftermath of the accord, many were optimistic about collective global action, expecting nations to swiftly alter their trajectories amidst mounting climate crises. Yet, numerous factors have intervened—far-right governments gaining ground, pandemic-induced upheaval leading to elevated inflation, and geopolitical strife detracting focus from climate priorities, leaving a trajectory of increasing emissions.

Nonetheless, many experts continue to support the multilateral approach embodied by the United Nations in addressing climate change. Rogelj noted, “While it’s evident that the Paris Agreement and the multilateral framework face significant challenges today, I don’t believe that any alternative would foster greater trust or collaboration among nations.”