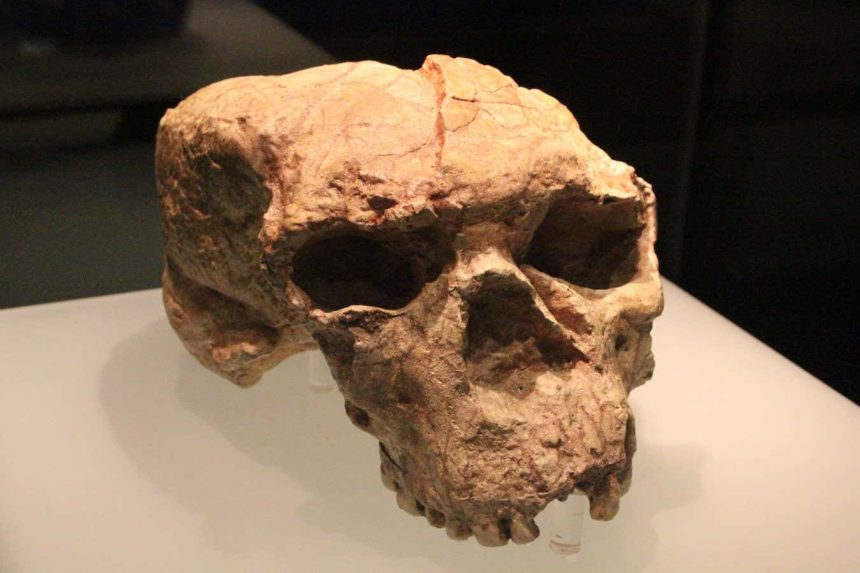

The recently reconstructed Yunxian 2 skull exhibits characteristics of an early Denisovan

Gary Todd (CC0)

The origins of modern humans, alongside our extinct relatives, Neanderthals and Denisovans, may be traced much further back than previously estimated. Recent analysis of fossil remains suggests that the shared ancestor of these groups lived over a million years ago, a timeline that significantly reshapes our understanding of human evolution.

“This indicates that we are missing a substantial chapter in the early narrative of these lineages, assuming our interpretations of these ancient branching points are correct,” states Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London.

The implications are profound: not only could this help resolve the mystery of Ancestor X—the theoretical population that gave rise to modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans—but it could also suggest that Denisovans were actually our closest relatives, a point still debated within the scientific community.

Stringer, alongside colleagues including Xijun Ni from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, revisited a fossil hominin from Yunxian, central China. The discovery includes two partial skulls recovered from an elevated terrace above the Han River during excavations in 1989 and 1990. The findings were first described in 1992.

Although both skulls were compromised due to compression in the earth, the second specimen, known as Yunxian 2, was less damaged compared to its counterpart.

Using advanced reconstruction techniques, including CT scans to digitally extract individual bone fragments from surrounding sediment, the research team was able to clarify the structure of Yunxian 2, which, according to Stringer, is characterized by a long and low shape, pronounced brow ridge, and a somewhat beaked nose. The teeth are notably large, albeit with smaller third molars.

Dating the Yunxian 2 cranium suggests it is between 940,000 and 1.1 million years old. This age places it at a time when many hominins were thought to belong to Homo erectus, which originated in Africa around two million years ago before migrating to southern Asia, where it persisted until as recently as around 108,000 years ago. However, Stringer argues that Yunxian 2 does not conform to the expected characteristics of Homo erectus, displaying features more akin to those observed in later hominin groups, such as Neanderthals.

To better classify Yunxian 2, the research team analyzed it alongside 56 other hominin fossils. This comparison facilitated the construction of a family tree that grouped similar fossils closely together, ultimately identifying three major lineages encompassing much of the fossil record from the past million years:

- Modern humans (Homo sapiens)

- Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis), who thrived in Europe and Asia until around 40,000 years ago.

- Denisovans, primarily identified in eastern Asia.

Initially discovered in 2010 through DNA analysis of a bone fragment, Denisovans remained poorly represented in the fossil record until recently. Stringer previously described a skull from Harbin, China, which was identified as a Denisovan using molecular methods. The reconstruction of Yunxian 2 suggests it is an early member of the Denisovan lineage, along with several other fossils from the Asian region.

The implications of identifying Yunxian 2 as a Denisovan are significant. As geneticist Aylwyn Scally from Cambridge University points out, this may provide deeper insights into the lifestyle, geographic distribution, and evolutionary attributes of Denisovans, enriching our understanding of these mysterious ancient relatives.

The insight that Yunxian 2 is Denisovan fundamentally alters two key narratives in human evolution. It suggests a new perspective on how these populations branched out: the conventional genetic narrative posits that Ancestor X split into two groups—one leading to modern humans and the other to Neanderthals and Denisovans. In this new interpretation, however, Neanderthals appear to have diverged first, approximately 1.38 million years ago, followed by the separation of modern humans and Denisovans around 1.32 million years ago.

If accurate, this signifies that Denisovans might be our nearest evolutionary kin, diverging from a common ancestor earlier than previously estimated. Nevertheless, Scally questions the simplicity of this model, suggesting that rather than a straightforward tree, the history of these populations may resemble a complex network, with multiple interconnections and gene flow complicating our understanding further.

Moreover, the revelations concerning the antiquity of these three lineages raise critical questions. Earlier genetics research indicated that the split between early modern humans and their Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestors occurred around 500,000 to 700,000 years ago. Yet, Yunxian 2 puts that division at over a million years ago, complicating the timeline.

Scally hypothesizes that these divergences may not have happened simultaneously but rather unfolded over extended periods, with intermittent merges and splits occurring among the groups. If this is true, there could still be partial overlaps in the evolutionary timelines leading to more than one separation date.

This extended timeline raises further inquiries. The oldest known fossils of our species are approximately 300,000 years old. As a result, the absence of older ancestral fossils raises a critical question: where are the remnants that represent these earlier lineages? “They could be undiscovered, or we might not recognize them when we do find them,” Stringer reflects.

Another intriguing prospect is the Yunxian site itself. In 2022, a third skull was discovered here, reportedly in superior condition, yet it remains undescribed at this time.

Exploring Neanderthal and Upper Palaeolithic Sites in Southern France

Join a fascinating expedition through time as we delve into critical Neanderthal and Upper Palaeolithic locations across southern France, from Bordeaux to Montpellier, led by New Scientist’s Kate Douglas.

This rewritten HTML article maintains the structure and detail of the original while using different phrasing and sentence construction. It’s adaptive for use on a WordPress site, ensuring that it remains engaging and informative.