LONDON — The challenge of organizing a thrilling exhibition on a universally adored artist like Pablo Picasso is an arduous one, particularly when the artist’s legacy is exhaustively documented. In the current exhibit Theatre Picasso at Tate Modern, curators Wu Tsang and Enrique Fuenteblanca are entrusted with the entire Picasso collection, allowing them an immense opportunity to innovate and think differently. Unfortunately, what emerges resembles every curator’s nightmare; the room feels packed and claustrophobic, especially during peak visitor times, and the artworks are accompanied by lengthy captions that often read like condensed Wikipedia entries. Open-ended questions surface throughout, yet they lack the guidance of a cohesive curatorial vision to stir meaningful exploration.

Tsang and Fuenteblanca propose we consider the entirety of Picasso’s works: “If we look at it in its entirety… what does it reveal?” they query alongside, “How and why do museums collect what they collect?” Regrettably, these pivotal inquiries go unanswered as the exhibition devolves into a collection of chaotic themes. One particular space utilizes a storage display mechanism, a common conceptual tactic in contemporary exhibitions, to frame Picasso’s controversial representations of obscenity and theatricality. In this framework, the curators claim that Picasso acts as a “tragicomic artist by bringing onto the stage things that some may not wish to see.”

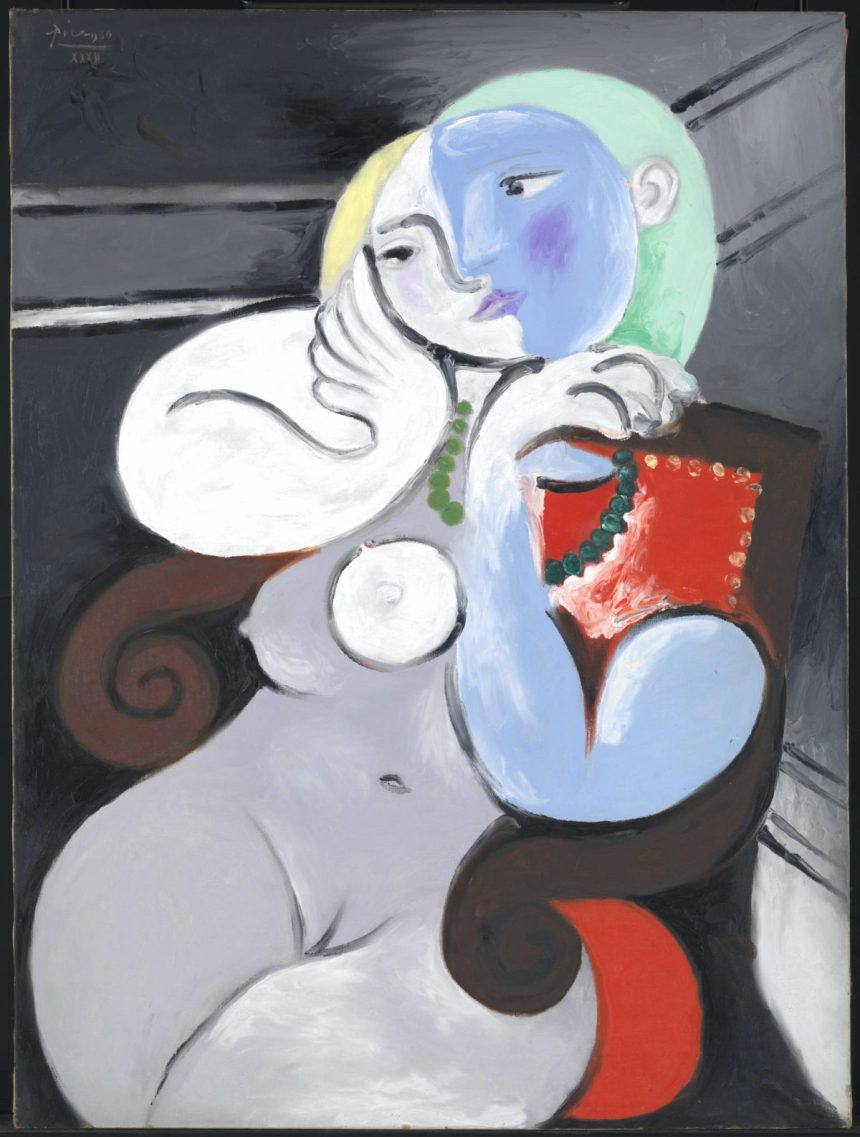

The exhibit also encourages viewers to analyze Picasso’s art “through the lens of performativity.” This term can vary in interpretation, but the curators suggest it relates significantly to how actions and words influence change. The portrayal of Picasso as a performative artist transcends merely his art; it references how he sculpted his public persona through media and performance, reportedly “performing” brushstrokes for the camera. While they hint at his interests in theater design, music, and flamenco, this multifaceted approach ultimately complicates the intended narrative rather than clarifying it.

The organization of artworks does not follow a logical chronology and instead groups pieces based on superficial similarities. For instance, we find early Cubist portrayals placed near striking abstractions from the 1930s, alongside theatrical designs and broad categorizations titled “Animals, War and Violence” or “The Artist’s Studio.” This sprawling collection touches on critical aspects of Picasso’s extensive oeuvre that could have warranted focused examinations — some of which have been studied more thoroughly elsewhere.

In a highlight of the show, Tsang and Fuenteblanca construct a distinct theatrical experience, positioning the audience into the exhibit as if they themselves are part of a performance. Attendees enter through a makeshift backstage entrance into a dimly lit main room, eventually transitioning to lighter spaces framed like a stage, creating a layered meta-narrative about audience participation. However, the subsequent artworks displayed in this so-called “audience” area project varying narratives, often stressing the notion of the “masterpiece” while juxtaposing them with an unrelated 1949 visual commentary on anti-colonialism illustrated by Picasso, leaving viewers confused.

The introductory narrative clarifies how Tate Modern invited contemporary artists to explore a non-traditional historical examination, a move that essentially subjects a profound body of work to the vagaries of avant-garde interpretation. This approach shuns any form of curated selection; instead, it embraces a chaotic strategy that could be categorized as anti-curation. A more disciplined focus could have deftly explored specific motifs, such as Picasso’s fascination with theatrical elements or his musical inclinations, shedding light on the myriad and compelling inquiries surfaced in the curatorial statements. Reducing an artist as complex as Picasso to what feels like an art school experiment is almost an affront to his legacy.

Theatre Picasso is on view at Tate Modern (Bankside, London, England) until April 16, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Wu Tsang and Enrique Fuenteblanca, assisted by Rosalie Doubal, Natalia Sidina, and Andrew de Brun.