Miko Vergun, one of the plaintiffs in the groundbreaking 2015 federal youth climate lawsuit Juliana v. United States, which challenged the constitutionality of decades of governmental support for fossil fuels, expressed no surprise when President Donald Trump announced three executive orders on the first day of his second term aimed at advancing oil, gas, and coal extraction in the name of energy security. However, she was still “disheartened” to see her government intensify its fossil fuel support despite the evident harms of climate change.

Three months later, Vergun received the disappointing news that the U.S. Supreme Court would not revisit its 2020 dismissal of the Juliana case; after ten years, her legal fight had come to an end. “After Juliana, to be honest, I had lost hope,” she shared with Grist.

The Juliana lawsuit marked the beginning of a wave of legal actions initiated by the nonprofit law firm Our Children’s Trust on behalf of young plaintiffs. In August 2023, they secured a victory against Montana in a case advocating for a “fundamental constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment,” which mandates the state to account for greenhouse gas emissions and their effects during its permitting process. Following that, in 2024, the state of Hawai’i reached a settlement with Our Children’s Trust, agreeing to decarbonize its transportation system and achieve zero emissions by 2045.

This past spring, Our Children’s Trust invited Vergun to be part of another lawsuit, contesting the constitutionality of Trump’s executive orders—“Unleashing American Energy,” “Declaring a National Energy Emergency,” and “Reinvigorating America’s Beautiful Clean Coal Industry.”

Initially, Vergun was hesitant. “It’s easy to fall into a nihilistic mindset during these uncertain times,” she remarked to Grist, “but one day I just thought, ‘Yes, I want to be part of this.’”

In September, following the preliminary court proceedings, Vergun, her attorneys, and 21 other plaintiffs aged 7 to 25 gathered in a Missoula, Montana, courthouse for an evidentiary hearing in their new case, Lighthiser v. Trump. This session resembled a mini-trial, giving both sides the chance to present their case and interrogate witnesses. The testimonies reflected Our Children’s Trust’s approach and illustrated their evolving legal strategy.

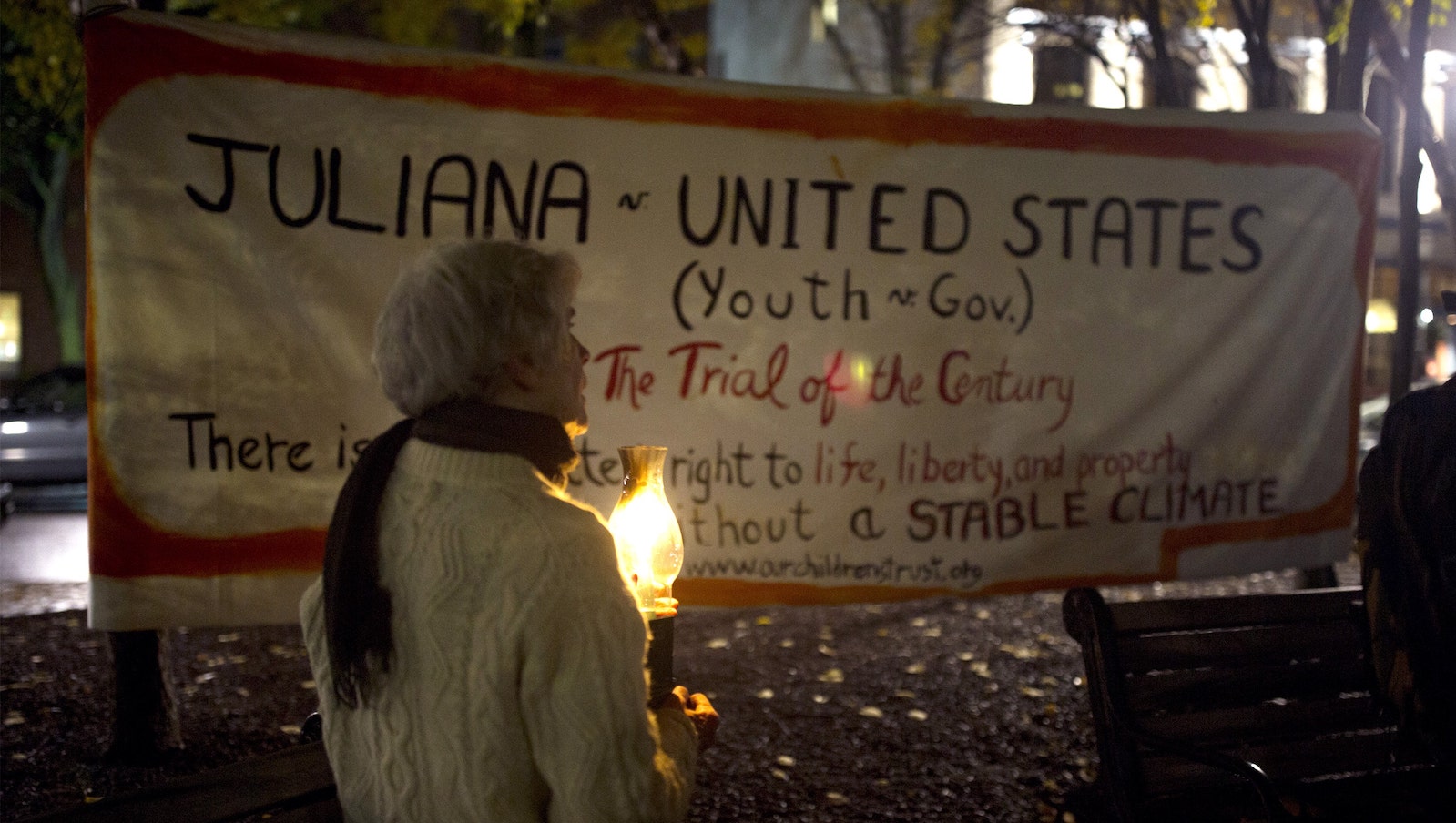

Photo by Alex Wroblewski / AFP via Getty Images

On the hearing’s opening day, gray fog enveloped downtown Missoula, but the youthful plaintiffs exuded enthusiasm as they walked toward the red-brick courthouse, passing a pathway adorned with marigolds. A crowd of about 100 supporters wielding signs cheered as they entered, ascending to the second floor. Once everyone took their seats in the long wooden rows facing the judge’s bench, Julia Olson, lead attorney for the plaintiffs, began her opening statement. “This case poses a fundamental question,” she stated. “Does the United States Constitution protect against abuses of power from executive orders that infringe upon children and youth’s fundamental rights to life and liberty?”

This query, noted Mary Wood, a law professor at the University of Oregon, sets Lighthiser apart from Juliana. While the prior case sought a court order mandating the government to devise and implement a climate change remediation plan, this time the plaintiffs are asking for a more focused remedy—a halt to the enforcement of the three specific executive orders. “It’s a direct appeal to prevent ongoing harm,” Wood explained.

However, government attorneys did not concede this point. “Here we are again, dealing with the same legal claims,” asserted Department of Justice lawyer Michael Sawyer in his opening statement. He maintained that the plaintiffs wished the courts to “intervene and oversee the nation’s energy policy.”

With the defendants opting not to call any witnesses, Our Children’s Trust was allotted two days to present their case, beginning with testimonies from young plaintiffs. The first to take the stand was Joseph Lee, a 19-year-old from Fullerton, California, with glasses and long bangs, dressed in a dark suit on sneakers. He raised his right hand, marking the first instance of a youth testifying in a federal climate case against the U.S.—an achievement Our Children’s Trust had pursued for over a decade. From the witness stand, Lee shared his experiences growing up near an oil refinery and developing asthma, and how heat, humidity, and wildfire smoke made it feel like his lungs were submerged in water, resulting in multiple hospitalizations, including one where he was surgically intubated during a heatwave. “I’m not sure I can continue,” he admitted.

Olson queried him: “Will the cessation of the EOs end climate change?”

“No,” he replied, “but it will prevent it from worsening.”

During cross-examination, DOJ attorney Erik Van de Stouwe points out the absence of air conditioning in Lee’s dorm at UC San Diego and how that exacerbates his asthma. “Yet you didn’t sue the State of California, correct?”

“To reduce my years of suffering to a mere issue of air conditioning is hurtful,” Lee responded.

The second witness, Jorja M., 17, recounted the moment she gathered her stuffed animals during a wildfire that threatened her home in Livingston, Montana. She described a 2022 flood that reached the doors of her family’s veterinary clinic, despite not being on a floodplain. Jorja illustrated how coal dust from passing trains coated her home, irritating her respiratory system. The coal was sourced from the Colstrip plant, which was supposed to close but will remain operational due to Trump’s executive orders.

As government attorney Miranda Jensen approached the stand, Jorja appeared anxious. “You mentioned that you have three horses, correct?” Jensen inquired.

“Yes,” Jorja confirmed.

“Are you aware that raising horses contributes to global warming?”

“I know that, yes,” Jorja responded.

“Are you troubled by the emissions your horses generate?”

Gasps echoed in the courtroom.

“I believe that having three horses generates minimal emissions,” Jorja replied.

After answering further questions, she returned to her seat, exchanging a knowing smile with Avery McRae, the next plaintiff.

Once sworn in, Olson asked McRae, 20, to recount her struggles caring for her horse and other animals amid Oregon’s wildfires and heat waves. She recalled coughing and feeling unwell. After moving to Florida for college, she encountered a different type of climate emergency, evacuating three times for major hurricanes during her first three years. “The entire campus was flooded with seawater,” she detailed, her composure tinted with frustration. She described the costs of her Airbnb, sheltering in a closet during a tornado warning, and having to return home to attend class via Zoom for five weeks.

During cross-examination, the government lawyer sought to clarify which climate events occurred before versus after the executive orders were signed.

Olson redirected the questioning. “Are you pursuing this case to rectify past offenses?”

Avery replied, “No.”

“Are you requesting the court to stop the EOs?”

“Yes.”

With these testimonies, Our Children’s Trust began to construct its fundamental argument— that its clients are experiencing distress due to climate change, and the executive orders will exacerbate these effects, infringing upon their constitutional rights to life and liberty. Their strategy for the rest of the hearing heavily relied on what Wood referred to as “an all-star cast” of factual witnesses.

The afternoon session began with Steve Running, a distinguished witness in a gray suit, humorously acknowledging his senior status. Running, a co-recipient of the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, testified to the established science connecting fossil fuel combustion to greenhouse gas emissions, which warm the planet and harm the plaintiffs. “Every additional ton of CO2 matters globally and critically impacts these plaintiffs,” he asserted. Asked about the anticipated effects of the executive orders on the youth’s injuries, Running confirmed, “Unquestionably.”

The courtroom buzzed with energy as Olson called John Podesta, a prominent figure who advised former President Joe Biden on clean energy and climate issues when Juliana was in pretrial motions. His presence was noteworthy, given that the Biden administration previously felt the arguments in Juliana were too expansive to implement.

Olson inquired of Podesta about the creation and administration of executive orders. She then asked: “Mr. Podesta, if an executive order were to be enjoined, can [government officials] ensure the enforcement of that court-ordered injunction?”

“It would be every federal employee’s duty, having taken an oath of office, to comply with that directive, including the president,” he replied. During cross-examination, Sawyer from the DOJ aimed to underscore the government’s defense, asserting that the plaintiffs were essentially asking the court to intervene in a policy debate. “President Biden also issued executive orders on his first day, correct?” he queried.

Podesta confirmed this, replying, “Yes.”

Sawyer proceeded to lead Podesta through a series of questions about Biden’s executive orders designed to address climate change, highlighting how Trump’s orders revoked those initiatives. The crux of Sawyer’s argument was that it’s standard for presidents to revoke previous administrations’ policies via executive action.

After the day’s proceedings wrapped up, youthful plaintiffs exchanged warm banter with the experts, expressing gratitude for their support. All the experts had offered their testimonies pro bono. The dawn of the second day broke bright, as sunlight spilled over the golden hills surrounding Missoula. The young plaintiffs remained in their wooden bench rows, whispering and laughing as the lawyers prepared to begin again. The witnesses included an energy economist, a pediatrician, and one final young plaintiff.

In her closing arguments, Olson reiterated the distinctions between Lighthiser and Juliana, emphasizing the harm her clients were facing, which she contended was exacerbated by the government’s actions. The judge interjected, “What exactly do you want me to do?”

<p“The remedy is straightforward,” Olson replied. “It involves halting the enforcement of the three executive orders and the specific provisions we’ve claimed are infringing upon the plaintiffs’ rights.” The judge voiced concern that ruling in their favor could lead to a continual judicial oversight of the administration’s actions.

Your Honor, it’s not about choosing policies,” Olson countered. “The Supreme Court has affirmed repeatedly that fundamental rights to life and liberty are not subject to votes. If policymakers could choose to endanger children’s lives, then the Bill of Rights would hold no meaning.”

In the government’s closing remarks, Sawyer concurred that the judge had rightly expressed concerns about intervening in a policy matter that ideally should be resolved by Congress and the executive branch. He cautioned that linking governmental actions to rights harms and elevates “safety-ism.”

Judge Christensen has not yet indicated when he will render a decision on the plaintiffs’ request for a preliminary injunction, which would suspend the executive orders until a formal trial is conducted. The defendants have also submitted a motion to dismiss that awaits the court’s attention.

Mat Dos Santos, co-director of Our Children’s Trust, noted that all youth climate lawsuits, including Lighthiser, aim to enforce constraints on government actions—similar to bumpers in a bowling alley—wherein governments must consider greenhouse gas emissions and the welfare of children in their policy decisions.

The pivotal question confronting the judge, according to Michael Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, is whether there exists a constitutional foundation for the court to intervene. He asserted that invalidating executive orders “is possible in the right circumstances, assuming there is a legal justification for it.”

For her part, Miko Vergun remains optimistic. “I’m just anticipating good news, to be honest,” she expressed.