The impact of redlining on neighborhoods in the 1940s is still being felt today, with residents of redlined areas facing higher mortality rates and shorter life expectancies, according to a recent study by researchers at the University at Buffalo and Texas A&M University. The study, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, highlights how legalized racial discrimination through redlining has had long-lasting effects on communities.

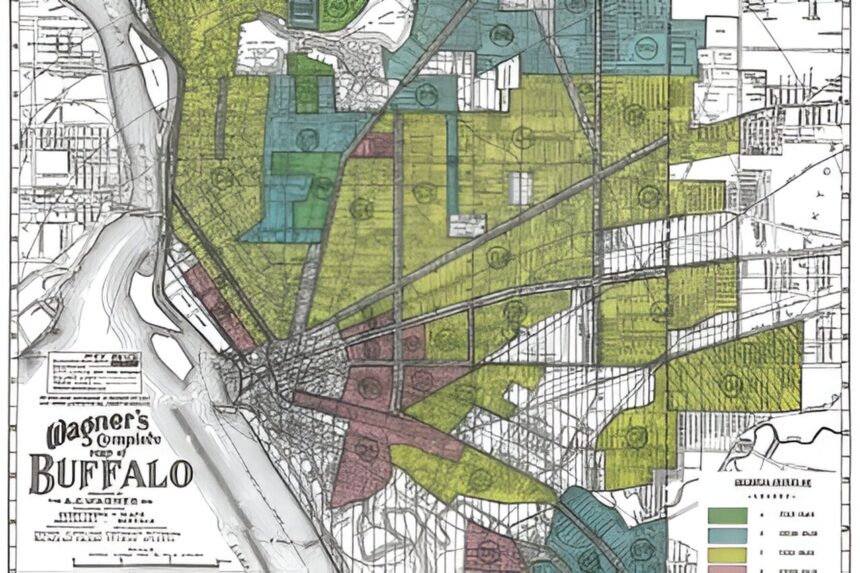

Redlining, a practice initiated by the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933, categorized neighborhoods based on their perceived creditworthiness. Green areas were deemed the most creditworthy, while red areas were considered the worst. These redlined neighborhoods were predominantly home to racial and ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans. The study found that individuals living in redlined neighborhoods had an increased risk of premature death and a shorter life expectancy compared to those in higher-rated areas.

The researchers used data from the Mapping Inequality project to analyze the impact of redlining on mortality rates. They found that each drop in HOLC rating was associated with an 8% increased risk of death later in life, resulting in a decline in life expectancy of nearly half a year. Individuals in redlined neighborhoods had a life expectancy gap of 1.47 years compared to those in the best-rated neighborhoods.

The effects of redlining are still evident today, with neighborhoods that were historically redlined experiencing disparities in health outcomes and mortality rates. In cities like Buffalo, where redlining maps were created, the segregation and discrimination that occurred in the 1940s continue to impact residents’ health and well-being. The study also highlighted how redlining created barriers to wealth-building and capital flow in minority neighborhoods, perpetuating social risk factors and contributing to adverse health outcomes.

Despite the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawing redlining, the study shows that the effects of this discriminatory practice persist. Communities that were redlined in the past continue to face health disparities and reduced access to resources and opportunities. Researchers are now focusing on addressing the impacts of structural racism on health disparities and finding ways to mitigate these effects.

The study underscores the need to acknowledge and address the legacy of redlining in order to promote health equity and social justice in communities across the country. By understanding the historical context of redlining and its lasting effects, policymakers and healthcare providers can work towards creating more equitable and inclusive environments for all residents.