A remarkable collection of life-sized animal rock engravings found in the Northern Arabian Desert suggests that this arid area may have been inhabited as far back as 12,000 years ago, challenging earlier assumptions about its uninhabitability. The findings, published in Nature Communications last month, help bridge a significant gap in the archaeological record at the end of the last Ice Age and the onset of the Holocene epoch.

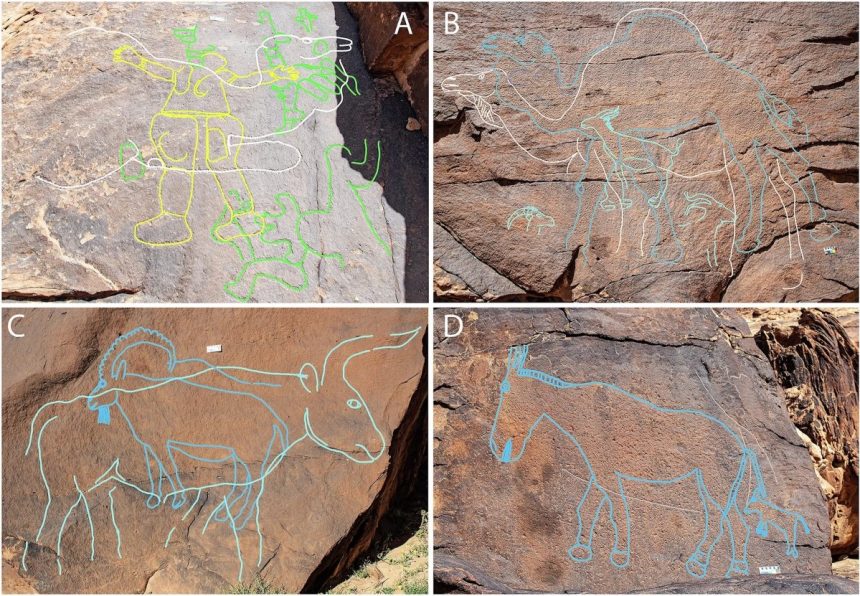

During an exploration of three previously unexamined locations in Saudi Arabia’s Nefud Desert—Jebel Arnaan, Jebel Mleiha, and Jebel Misma—researchers uncovered 176 large petroglyphs etched into sandstone cliffs and boulder faces. These intricate designs, found coated with a thick, dark rock varnish, were chiseled into high ledges at elevations reaching up to 128 feet.

The archaeologists noted that “the challenge of accessing and carving these rock surfaces, combined with their increased visibility from a height, were evidently appealing for the engravers,” who “likely took considerable risks to create this artwork.”

This study, conducted in 2023 by an international team led by archaeologist Maria Guagnin from the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, was financed by the Saudi Heritage Commission. This body was established as part of the Saudi government’s ambitious Vision 2030 initiative, which has faced scrutiny for its potential to obfuscate ongoing human rights violations.

Most of the petroglyphs illustrated animals adapted to desert life, including wild camels, gazelles, ibex, and horse-like mammals, alongside occasional human figures and a depiction of an extinct bovine ancestor. These images were frequently found layered over earlier, “more cartoonish” art, suggesting a stylistic shift over time, the researchers observed.

Scholars speculate that ancient nomadic hunter-gatherer groups may have utilized these engravings as a means of documenting freshwater sources, thereby refuting past assumptions that human activity was absent during that era. During this time, erratic cool weather patterns led to extensive dryness across the Arabian Peninsula, triggering dune migrations and significant population movements away from the area.

The researchers’ hypotheses gained support from sedimentary analyses revealing the existence of seasonal lakes, which would have enabled early inhabitants to thrive in an otherwise parched landscape. The authors highlighted the notable engraving of the bovine, which was an “obligate drinker” and could not survive without access to freshwater.

“These engravings, potentially made over thousands of years, would have served as reminders of ancient beliefs and symbolisms of their community, likely influencing their seasonal lifestyles and enhancing their resilience in these challenging environments,” the authors stated.

Additionally, researchers uncovered 16 bone fragments along with 1,200 stone tools and decorative beads from the three excavation sites. They theorize that these artifacts, many found directly beneath the rock engravings, suggest interactions between early Arabian communities and neighboring populations in the Levant, necessitating long-distance travel along intricate routes.

The researchers concluded that “the enduring nature of these images may have aided the retention of their meaning and symbolism throughout generations of individuals utilizing these sites.”