Rabies is a deadly disease that still takes the lives of 70,000 people worldwide each year. In a recent study conducted in Peru, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania uncovered gaps in the surveillance of dog-related rabies, particularly in disadvantaged neighborhoods where more dogs were found to have the disease compared to wealthier areas.

Lead researcher Ricardo Castillo, Ph.D., DVM, MSPH, emphasized that the people most at risk of rabies were also the least visible to the surveillance system. This disparity in tracking rabies cases highlighted the importance of evaluating methods for equity in public health efforts.

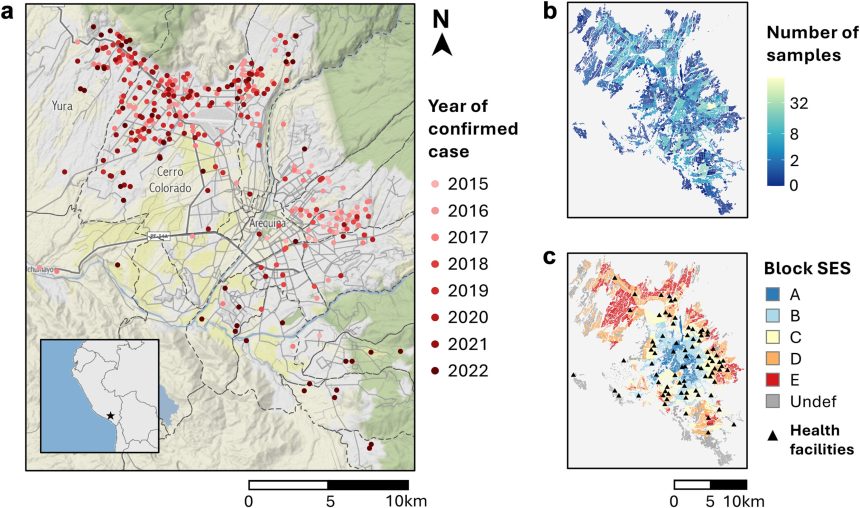

In Peru’s second-largest city, Arequipa, rabies in dogs had been eradicated for many years but re-emerged as a significant threat. Dogs are responsible for 99% of recorded rabies cases globally, making tracking cases in canines crucial to preventing outbreaks among humans. The study found that the passive surveillance strategy in place, which relied on people reporting dead dogs, was ineffective in disadvantaged neighborhoods due to structural barriers and lack of awareness about rabies.

To address these shortcomings, the research team implemented an active surveillance system in partnership with Cayetano Heredia University in Lima. This system involved regular patrols of specific areas where dead dogs were often found, supplementing the passive reporting system. The active surveillance approach proved to be successful in identifying rabies cases in high-risk areas.

By analyzing data from 2015 to 2022, the researchers discovered that surveillance efforts were not adequately focused on the most vulnerable neighborhoods. Samples collected through passive surveillance disproportionately came from lower socioeconomic status blocks, highlighting the need for more equitable distribution of resources and access to healthcare services.

The implications of this study extend beyond Peru, with rabies remaining a major concern in various regions worldwide, including the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. The research findings underscore the importance of addressing health inequities in surveillance and control efforts to prevent the spread of rabies and other animal-borne diseases.

As climate change and migration continue to impact disease dynamics, lessons learned from studies like this one in Peru can inform preparedness and elimination strategies globally. Ultimately, tackling rabies is a shared health challenge that requires collaboration and equitable distribution of resources to protect communities from this deadly disease.