Unveiling the Secrets of the Universe’s Primordial Soup

Right after the Big Bang reverberated through the cosmos, the Universe was a seething trillion-degree ‘soup’ of incredibly dense plasma. In a groundbreaking experiment, scientists have unearthed the first proof that this exotic primordial concoction did indeed ripple and swirl like a thick soup.

Known scientifically as quark-gluon plasma, or QGP, this viscous soup was the first and hottest liquid to ever exist. Estimates indicate that it blazed a billion times hotter than the Sun’s surface for a fleeting moment before cooling down and transforming into atoms.

A recent study conducted by a team of physicists from MIT and CERN involved recreating heavy-ion collisions similar to those that produced the QGP in order to investigate its characteristics. One of the key questions was how quarks behaved when traversing the plasma – did they move cohesively like a liquid or scatter randomly like individual particles?

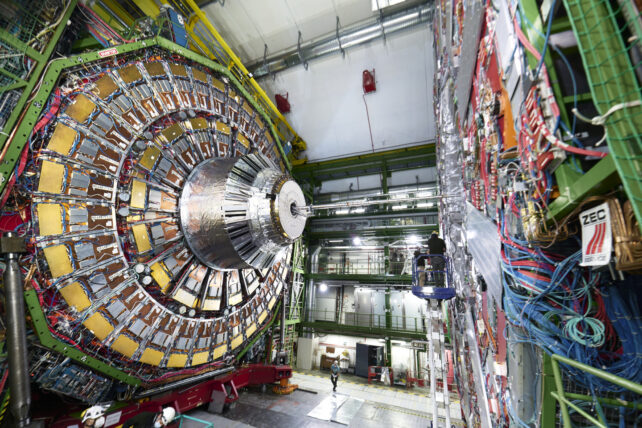

The researchers delved into data from collisions between lead particles accelerated to nearly the speed of light inside CERN’s Large Hadron Collider (LHC). These collisions generated sprays of energetic particles, including quarks, as well as a droplet of the QGP that permeated the early Universe.

Employing a novel approach that offered a clearer picture of the heavy-ion collisions than previous experiments, the physicists tracked the movements of quarks within the QGP and mapped the energy distribution of the QGP following these collisions.

“We now see that the plasma is so dense that it can decelerate a quark, resulting in splashes and swirls akin to a liquid. Therefore, quark-gluon plasma truly represents a primordial soup,” stated physicist Yen-Jie Lee of MIT.

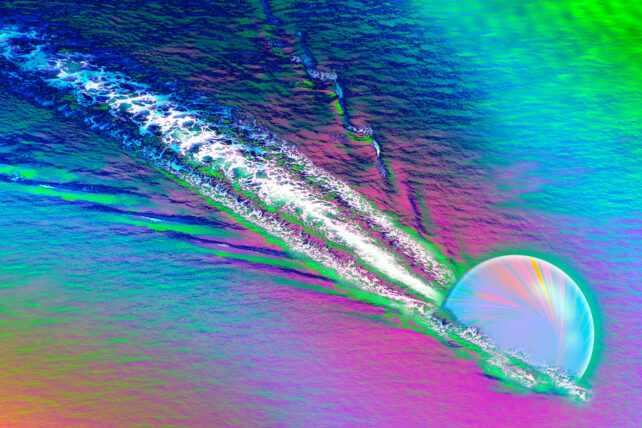

As quarks traverse the QGP, they transfer some of their energy to the plasma, slowing down and creating a wake similar to a speeding boat.

MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, who devised a model predicting the fluidic properties of QGP, likened the phenomenon to a boat moving through water, leaving a wake behind it. This transfer of momentum from the quark to the surrounding plasma causes the swirling motion.

Unlike the clean wake seen in water, detecting the presence of this wake in the QGP droplets was a complex task. It involved sifting through tens of thousands of interacting particles in a trillion-degree plasma, typically existing within the LHC for a minuscule fraction of a second, to identify the few particles affected by the quark’s wake.

According to Rajagopal, quarks generated in LHC collisions are always accompanied by antiquarks, their oppositely charged counterparts. As a result, detecting the wake created by a single quark amidst this chaotic environment posed a significant challenge.

Instead of focusing on quark-antiquark pairs as in previous studies, the physicists sought out a different particle pair. In some instances, LHC collisions produced a quark along with a Z boson, a neutral elementary particle that does not interact with the QGP and thus does not create a wake.

Although events generating a quark-Z boson pair were rare – with only about 2,000 occurrences out of 13 billion collisions analyzed in the study – they provided crucial insight into the behavior of the QGP as a liquid, exhibiting swirling and sloshing motions in response to the quark’s passage.

Rajagopal emphasized that while this discovery represents “definitive, unmistakable evidence” of the liquid-like behavior of QGP, the debate over whether it flows and ripples like a fluid may persist as other researchers scrutinize the results.

Nevertheless, this innovative technique lays the groundwork for exploring similar phenomena in high-energy collisions, shedding light on one of the most enigmatic substances in cosmic history.

“In various scientific fields, understanding a material’s properties often involves perturbing it and observing how the disturbance propagates and dissipates,” Rajagopal noted.

And this is what makes physics so exhilarating – when faced with uncertainty, simply accelerate it to near-light speed and observe the magic unfold.

This research has been published in the journal Physics Letters B.