Air quality monitoring in the United States has come under scrutiny due to disparities in monitor locations, particularly in neighborhoods with predominantly white populations. A recent study conducted by the University of Utah revealed that the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) air quality monitors fail to adequately capture pollution levels in communities of color, especially in relation to pollutants like lead and sulfur dioxide.

The distribution of EPA regulatory monitors plays a crucial role in shaping decisions related to pollution reduction, urban planning, and public health initiatives. However, the unequal placement of monitors can lead to misrepresentations of pollution concentrations, putting marginalized communities at greater risk of exposure to harmful pollutants.

Lead researcher Brenna Kelly, a doctoral student at the University of Utah, emphasized the importance of questioning whose air quality is being measured by these monitors. The study highlighted significant disparities in monitor locations for various racial and ethnic groups, with communities of Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, American Indians, and Alaska Natives facing the largest monitoring gaps.

Furthermore, the study raised concerns about the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools in analyzing air quality data, noting that biases in the datasets themselves could impact the accuracy of findings. Simon Brewer, a co-author of the study and an associate professor of geography, underscored the need to reevaluate the decision-making process behind monitor placement to ensure equitable distribution.

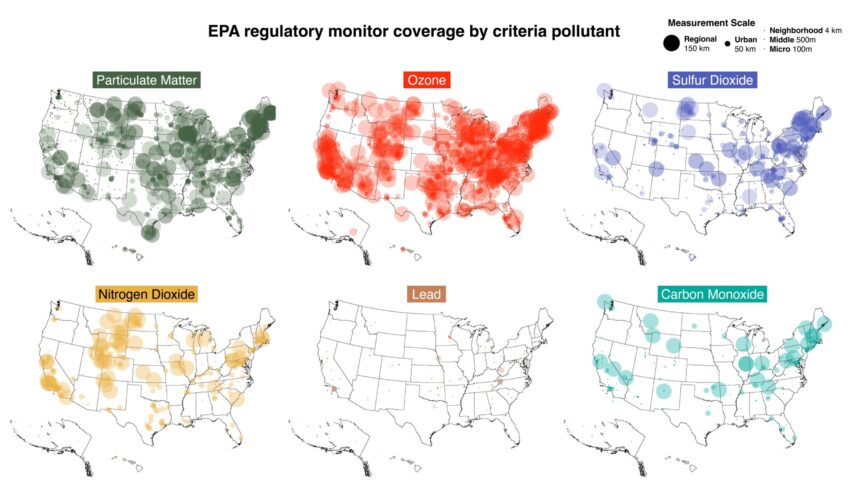

Published in JAMA Network Open, the study utilized census-block level data to map monitor locations and demographic information across the United States. By examining six major air pollutants, the researchers identified systemic monitoring disparities for non-white populations, indicating a need for more inclusive and representative monitoring practices.

The findings of the study have significant implications for public health research and policy-making, highlighting the importance of addressing monitoring disparities to achieve more accurate and equitable assessments of air quality. As the world becomes increasingly reliant on big data and AI technologies, initiatives like the University of Utah’s Responsible AI Initiative aim to promote fair and unbiased data practices in various fields.

In conclusion, the study underscores the critical need for a more inclusive and equitable approach to air quality monitoring to ensure the well-being of all communities, regardless of race or ethnicity. By addressing disparities in monitor locations and data representation, researchers and policymakers can work towards a more comprehensive understanding of air pollution and its impacts on public health.