Valerie A. Ramey from the Hoover Institution has recently published an intriguing NBER paper that delves into the effects of one-time transfer payments on overall economic demand. Below is the abstract of her investigation:

This paper reassesses the role of temporary transfers in stimulating the macroeconomy, drawing insights from four distinct case studies. Given the resurgence of Keynesian stabilization policies, which come with the burden of increased debt, it is crucial to evaluate their effectiveness. In each case study, I scrutinize whether the aggregate data supports the notion that these transfers act as a genuine economic stimulus. Two case studies revisit my prior research on the 2001 and 2008 U.S. tax rebates, while the other two offer fresh analyses of temporary transfers in Singapore and Australia. Across all four cases, the findings indicate that temporary cash transfers to households likely had minimal to no stimulative impact on the broader economy.

A particularly thought-provoking comment in the paper states:

I find no evidence that the election-year payouts in Singapore have stimulated the macroeconomy. These results align with the findings from the 2001 and 2008 tax rebates in the U.S. However, a puzzling question remains: why are the high household marginal propensities to consume (MPCs) identified by Agarwal and Qian (2014) not reflected in aggregate consumption? Lacking access to current micro data, I must defer the resolution of these conflicting micro and macro results to future research.

Let’s consider the 2008 tax rebates as a case study. For illustrative purposes, imagine that 75% of households received a $1,000 check, while the remaining 25% did not benefit from this rebate. If we suppose that those who received the rebate increased their spending by 4%, and that the other households remained unaffected, the overall consumption could see a 3% increase on average.

However, during this period, inflation was surging, primarily due to escalating commodity prices and a depreciating dollar. In response, the Federal Reserve opted for a tighter monetary policy. Interestingly, this was not reflected in an increase in interest rates; instead, the Fed maintained its target interest rate at 2%, despite a significant drop in the natural rate of interest by mid-2008. Let’s further assume that this tight monetary approach led to a 3% reduction in spending across all households.

Combining these effects, one might expect that households who received a tax rebate would spend 1% more (the initial 4% boost offset by the 3% reduction from tighter monetary policy), while the 25% of households without a rebate could be expected to consume 3% less. Thus, the monetary policy could effectively negate the expansionary impact of the fiscal stimulus.

This example serves merely as an illustration of the so-called “monetary offset.” It highlights the possibility that micro data (household spending behavior) may suggest fiscal stimulus efficacy, while macro data indicates otherwise. If monetary policymakers are fulfilling their roles correctly, they should consistently counterbalance any fiscal policy measures involving lump-sum taxes and transfers. (Notably, changes in marginal tax rates may induce supply-side effects.)

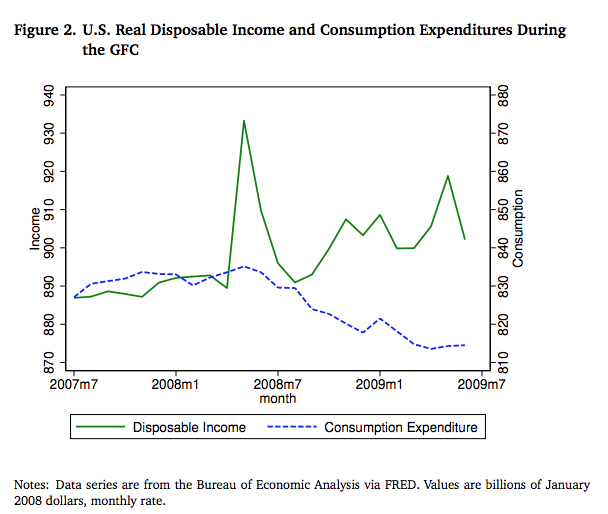

Ramey’s paper includes several graphs depicting shifts in disposable income versus consumption. A keen observer would note the sharp spike in disposable income in May 2008 due to the tax rebate, juxtaposed against a largely unchanged consumption pattern: