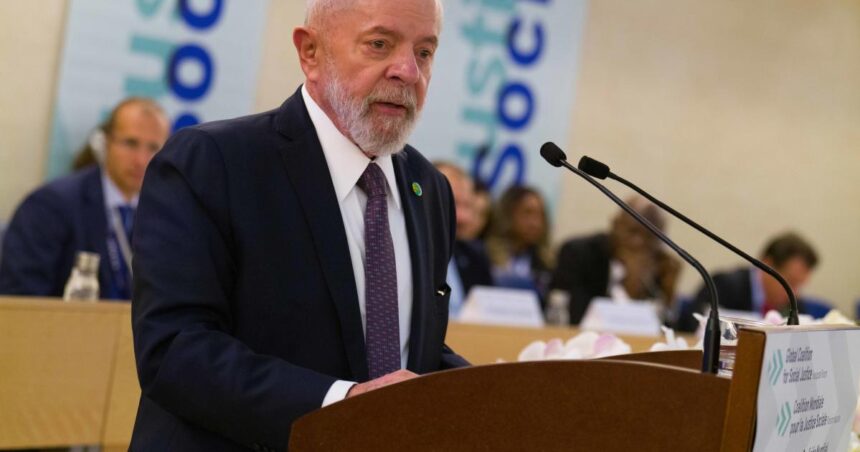

In June 2022, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, made headlines when he stated that he had no regrets about supporting the controversial Belo Monte dam project in the past. He expressed that if given the chance, he would make the same decision to build the dam again. Lula da Silva has been a staunch supporter of the Belo Monte project, despite the numerous criticisms and concerns raised by environmental and indigenous rights activists.

The Belo Monte project consists of two dams: the upper dam, Pimental, which diverts water to the canal, and the lower dam, Belo Monte, where the powerhouse is located. The construction of the dam resulted in the forced displacement of around 40,000 people, including riverside communities and a quarter of Altamira’s population. Many of these displaced individuals were relocated to remote resettlements on the outskirts of the city.

The impact of the Belo Monte dam on the local communities has been devastating. Indigenous people and riverside communities lost access to their primary food source – fishing – as the fluctuating water levels led to the extinction of fish species. The diversion of the river’s natural course reduced its flow by 80%, further exacerbating the environmental damage caused by the dam.

One such individual who has been deeply affected by the Belo Monte project is Maria Francineide Ferreira dos Santos. She lost her home in Paratizinho after speaking out against the destruction caused by the dam. Despite facing threats and having her home demolished while she was away for medical treatment, she continues to fight for justice and the protection of the river and its people.

The construction of the Belo Monte dam has had far-reaching consequences on the region, including increased food insecurity among the displaced communities. A study published in the Environmental Research and Public Health journal highlighted the alarming levels of food insecurity in the impacted areas. The disruption of essential food sources like agriculture and fishing has led to increased poverty and hunger among the affected populations.

The social and environmental impacts of the Belo Monte dam have been severe, with ecologist and activist Rodolfo Salm describing it as a clear example of failure on multiple fronts. Despite significant investments in compensation and promises of economic development, the project has left the region economically weakened and environmentally damaged.

The resettlement process for the displaced communities has also failed to address their needs adequately, leading to a deepening of vulnerabilities and food insecurity. The disruption of the river’s natural balance has had profound effects on the Indigenous and riverside communities whose lives are intertwined with the Xingu River.

As Brazil prepares to host COP30 and showcase its commitment to climate leadership, the question of whether a nation can truly claim such leadership while ignoring the voices of those sacrificed in the name of energy remains unanswered. The lessons learned from projects like Belo Monte should serve as a warning against prioritizing large dams in biodiversity hotspots like the Amazon.

The construction of hydropower dams in such regions has irreversible consequences for both the environment and local communities. The damage caused by these projects, both ecologically and socially, far outweighs the benefits they promise. It is time for a fundamental shift in energy policy that prioritizes sustainability, human rights, and environmental protection over short-term gains.

In conclusion, the story of the Belo Monte dam serves as a cautionary tale about the true costs of large-scale development projects in sensitive ecosystems. As we look towards a future powered by renewable energy, we must ensure that it is done in a way that respects the rights of all people and protects the natural world for future generations.