In nearly every dialogue surrounding political and societal issues, there’s often a knee-jerk reaction to assert that any disparity between two groups is per se indicative of discrimination against one of those groups. Yet, a closer look through the lens of statistical analysis reveals that this assumption can be misleading.

Take, for instance, the wage gap between men and women. While it is indeed true that women earn less than men, this discrepancy often correlates with the types of professions women typically enter—fields that may prioritize flexibility and security over higher salaries (think more time with family or safer work environments). When we adjust for these variables, the wage gap diminishes significantly.

Could discrimination against women still be present? Absolutely. Consider the following examples:

- Social norms may pressure women into choosing professions perceived as more ‘feminine,’ reinforcing the belief that women should be homemakers while men are breadwinners, nudging women toward more flexible, less lucrative jobs.

- The concept of “tracking” in education can also play a role: during the 1960s, for instance, school counselors often placed girls on tracks that led to classes in home economics and education, while boys were steered toward science and math.

- Furthermore, unpleasant workplace conditions can deter women from entering certain fields. It’s not uncommon to see female professors treated harshly by students compared to their male counterparts.

In all these situations, while wages may equalize after accounting for certain factors, they still represent forms of discrimination.

This illustrates that a mere discrepancy isn’t sufficient proof of discrimination; it merely signals the need for deeper investigation.

The same principle applies in the realm of politics. Recently, there have been claims suggesting that the unusually high number of nationwide injunctions against executive orders is per se evidence of “lawfare” targeting the current administration, suggesting a judicial coup is underway. Yet, just as before, this assertion requires more substantial evidence.

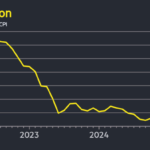

Indeed, there have been more nationwide injunctions against the Trump administration compared to his predecessors. During his first term, 84 injunctions were issued against him, while Biden faced 28, Obama had 12, and George W. Bush saw only 6. In the current term, approximately 25 injunctions have been filed (source for these numbers).

However, it’s also worth noting that President Trump has issued an unprecedented number of executive orders. In his first term, he issued 220 orders, averaging 55 per year—the highest rate since Jimmy Carter. Should the current administration continue on this path, it may issue an astonishing average of 1,312 orders per year, a level not seen since FDR’s initial term (source). With such a high volume of executive orders, it stands to reason that the likelihood of nationwide injunctions would increase simply by chance. Moreover, many of these orders are broad in scope, impacting a wide array of Americans, thereby raising the probability of judicial responses.

Proving discrimination is notoriously challenging. Essentially, one would need to demonstrate that an identical executive order, had it been issued by a different administration before the same judge, would have yielded a different outcome. This is no small feat, though not entirely impossible.

Similar to the wage gap scenario discussed earlier, discrimination may very well be at play. However, a discrepancy alone does not imply its existence; we require more substantial evidence.

—

PS: To preemptively address potential objections: The Supreme Court’s ruling in Trump v CASA does not serve as evidence of judicial discrimination. The ruling does not tackle that issue directly; in fact, it acknowledges that the prevailing situation for presidents from both parties is that “almost every major presidential act [is] immediately frozen by a federal district court” (see pgs 4–5).