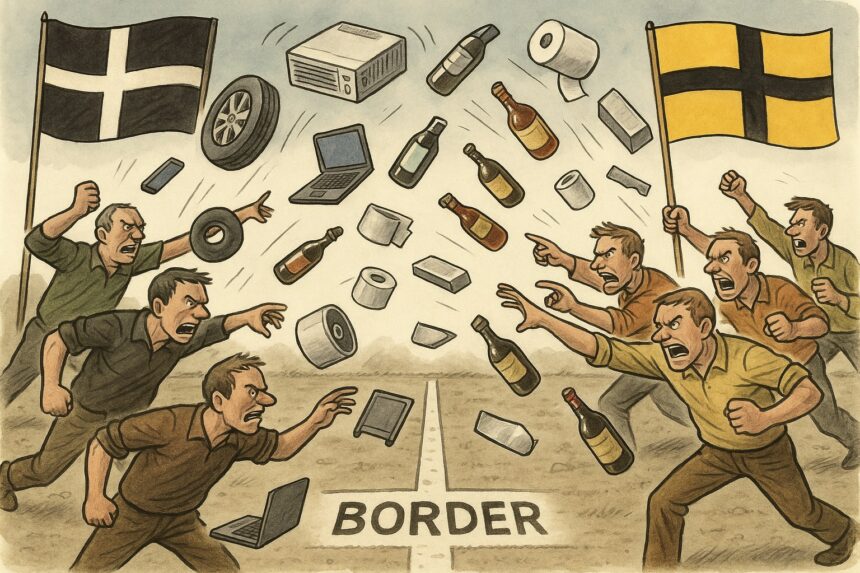

When we consider a free country to be a realm where individuals or private entities can engage in voluntary cooperation—especially through trade—it’s hard to overlook the inherent contradiction in the term “trade war.” After all, if trade is fundamentally about peaceful interaction, how can it simultaneously be described as a war?

This perspective on what constitutes a free country is not just an academic exercise; it has practical implications. First, a free society is valuable because it fosters equal liberty and the opportunities that contribute to collective prosperity—an assertion well-supported by economic theory. Second, to truly grasp the nuances of individual and societal interactions, we need to embrace methodological individualism. This means analyzing behaviors starting from individual preferences and self-interest. For instance, if “France” and “Canada” decide to cease trade, it’s only through methodological individualism that we can comprehend the inevitable smuggling that might ensue.

Of course, there are valid exceptions to the concept of free trade, particularly when its very existence is threatened—such as in the case of contracts for hire that lead to violence or the abhorrent trade in human lives. Scholars like James Buchanan have explored these limitations in works like The Limits of Liberty and The Calculus of Consent, pointing out that a state restricting its citizens’ freedoms in response to another state’s actions is, at least in peacetime, an unjustifiable stance.

However, if one subscribes to the notion that “countries” engage in trade, a moment’s reflection quickly reveals the absurdity of this idea. How can entities like “France” or “Canada” perform trade? They lack the capacity to think or act independently, possessing neither the limbs nor the consciousness to engage in such exchanges. The more grounded belief is that the political authorities in these nations interact, deciding who may trade and under what conditions. The implication here is that this top-down approach is seen as the only viable social structure.

In a landscape devoid of free societies, the specter of a trade war looms just as ominously as that of a conventional war. Historically, these two forms of confrontation have often been intertwined. The rulers of nations—whether elected or otherwise—have engaged in conflicts when such actions served their interests. The nature of their authority is less significant than the breadth of their power. Nonetheless, methodological individualism remains essential for understanding the motivations behind these rulers’ choices, including their adherence (or lack thereof) to principles of international law such as pacta sunt servanda.

******************************

“Trade War” by ChatGPT, with some guidance