For more than forty years, artist DY Begay has broadened the expressive capacity of Diné (Navajo) weaving, crafting a style that resonates uniquely with her identity. As a Diné Asdzáá (Navajo woman), she belongs to the Tótsohnii (Big Water) clan and is born for the Táchii’nii (Red Running into Water/Earth) clan. Her maternal lineage traces back to the Tséñjíkiní (Cliff Dweller) clan, while her paternal grandfather identifies with the Áshííhí (Salt People) clan.

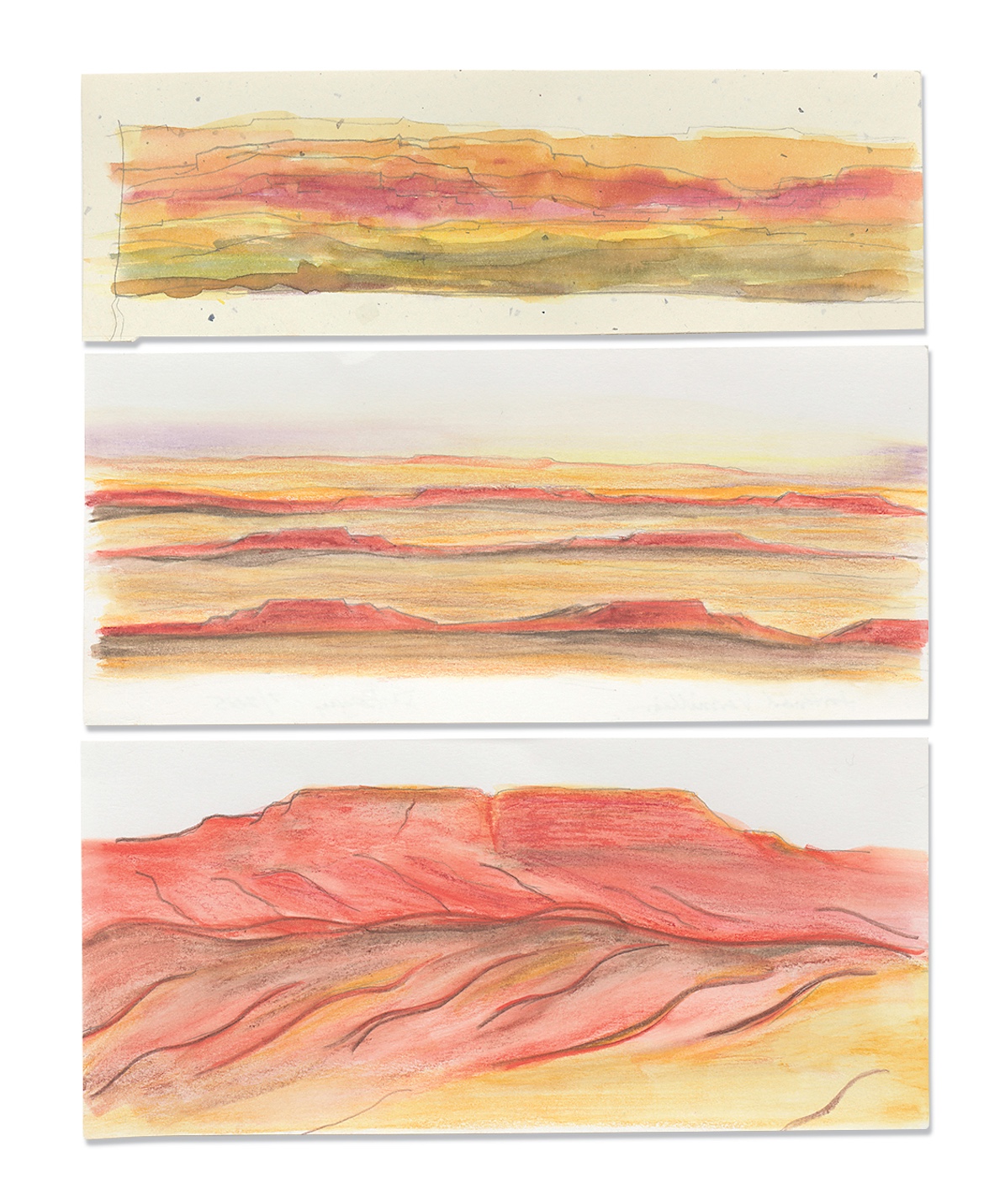

Begay, a fifth-generation weaver, grew up in Tsélání (Cottonwood) on the Navajo Nation, where her family continues to tend sheep. Her work reflects the vibrant hues of the Navajo landscape—blending reds, blues, and greens inspired by sunsets, mesas, and mountains—while her practice employs wool from her family’s sheep and natural dyes that connect her artistry to the land she cherishes and strives to safeguard.

In 1979, after graduating from Arizona State University, Begay transitioned to New Jersey, immersing herself in the New York City fiber art scene. She explored historic Diné textiles at the Museum of the American Indian, which later became a part of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). Many pieces in the museum come from Diné weavers whose identities remain unknown, often believed to be women. Influenced by renowned artists such as Anni Albers, Sheila Hicks, and Lenore Tawney—who themselves explored Indigenous weaving—Begay began to experiment with various Indigenous techniques. By 1985, she was actively advocating for Diné weavers to view their textiles as art rather than mere trade goods, a philosophy she has upheld throughout her prolific career.

Returning to Tsélání in 1989, Begay’s grandmother, Desbáh Yazzie Nez (1908–2003), witnessed her work and encouraged her to cultivate her distinct compositional style. She quickly garnered acclaim at events like the Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair and Market and the Santa Fe Indian Market, yet felt an internal drive pushing her to transcend conventional weaving boundaries. In 1994, this introspection led to a pivotal breakthrough: the development of color hatching—a technique enabling sophisticated color gradients that revolutionized the traditional solid, banded designs typical of Diné weaving.

This innovation established a new trajectory for her weavings, marking a shift towards color-driven abstraction through the introduction of undulating bands, as seen in her piece “Pollen Path” (2006), encapsulating her experiences of gathering corn pollen with her sisters. She is at the forefront of a movement to revitalize Diné wool garments, including the serapes that fell out of favor after the late 19th century due to ramifications of U.S. policies on Indigenous peoples. Her recent survey at the NMAI showcased 48 textiles primarily created over the last three decades and positioned her enduring career in the broader narratives of Diné heritage and contemporary art.

Having recently exhibited at the Santa Fe Indian Market in August, Begay recently shared insights over a Zoom interview from her Santa Fe studio. The conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Sháádiin Brown and Zach Feuer: In Sublime Light: Tapestry Art of DY Begay, the first publication singularly focused on your work and the retrospective at NMAI, you reflect on observing your mother and grandmother weave within the hogan. What was the catalyst for your first weaving, and how did those early works manifest? Can you discuss your early mentors?

DB: My earliest memories of weaving involve standing behind my mother’s loom, transfixed as her nimble fingers wove colorful yarns over and around the warps. Although I was too young to fully grasp the intricacies—potentially around four or five years old—I was captivated by the rapid formation of geometric patterns characteristic of a Ganado-style weaving.

My upbringing was steeped in weaving culture, surrounded by my maternal grandmother, mother, and aunts. Someone was constantly at the loom, often in a central position within our hogan. We lived in the hogan myself, contributing to a vibrant communal atmosphere.

I watched my mother devise intricate stepped designs using yarn dyed by hand, finding clarity in the physical act of weaving. In Diné Bizaad, the term kót’é means “like this”—the essence of her teachings, not through formal instruction but simply through demonstration and presence.

SB & ZF: Do you recollect the moment you initiated your own weaving—did your family assist in setting up a loom for you?

DB: My curiosity drove me. I attempted to manage my mother’s tools despite their size being unsuitable for my small hands. In her absence, I would sneak in front of the loom, pulling the weft through and trying to tamp it down, but it was often a failure. Eventually, she allowed me more freedom, guiding me with an encouraging “kót’é,” enabling me to familiarize myself with the weaving process.

By age eight, I had my own loom, albeit minor in size, using leftover yarn from my mother’s supplies. I completed my first weaving—possibly no larger than two colors—and fondly remember that experience as pivotal in my early creative journey.

SB & ZF: What transpired with those initial pieces? Did your mother bring them to a trading post?

DB: I am unsure of their fate; we would often trade finished weavings at local posts in exchange for various essentials. My early works that measured approximately two by three or three by three feet were typically taken by my father or grandfather. I do recall one specific weaving being showcased at the NMAI from 1966, which stands out as the only one I definitively recall.

SB & ZF: Can you share the inspiration behind “Pollen Path”? What approach did you take while creating this?

DB: In weaving “Pollen Path,” I aimed to weave in cultural significance—the act of sprinkling corn pollen holds great importance to the Diné, celebrated to honor a new day, receive blessings, and seek balance in life. Corn is a sacred crop, and the pollen is gathered during the summer’s peak—an act steeped in tradition, occurring just before dawn.

The project commenced in summer 2007, a bounteous season for plants yielding dyes for my wool. My sister, Berdina Y. Charley, cultivated local heirloom corn seeds gifted by our Táchii’nii relatives, facilitating a harmonious overlap between planting, weaving, and gathering pollen during that time. Each moment reflected peace, beauty, and deep gratitude.

SB & ZF: How do you embody the experience of walking in beauty amidst the landscapes of Diné Bikéyah (Navajo Country), particularly in your home of Tsélání, within your weaving?

DB: My memories of Tsélání are vivid, not only internal but aided by frequent photography to capture the shifting textures during different times of day. These photographs are used to evoke both two and three-dimensional forms in my loom work.

SB & ZF: With regards to your family’s sheep flock, how has it influenced your practice over the years?

DB: My family has maintained a sheep-rearing tradition for generations. Sheep were critical not only for food but also provided the wool necessary for weaving—an essential aspect of trade. Nowadays, my sister Berdina continues the tradition of raising Navajo-Churro sheep for both crafting and sustenance, ensuring that we retain this resource to consistently create yarn for our weaving.

SB & ZF: What about your color palette and dyeing process? Is utilizing earth-sourced dyes significant to you?

DB: I have practiced natural dyeing for years, delighting in deriving colors from local plant life. This method not only connects me to the earth’s offerings but honors my cultural heritage through traditional practices.

My palette derives from both local and non-native sources, using plants like cota (Navajo tea), rabbitbrush, and sage, alongside various insects, fungi, and other natural materials. Each plant has its season, and my collection aligns with the yearly cycle, making the dyeing process an experiment in both art and natural science.

SB & ZF: Were there specific experiences or individuals pivotal to your evolution as a weaver?

DB: Absolutely, I can identify two significant mentors. My paternal grandmother, Desbáh Yazzie Nez, was a distinguished weaver. Her reminders to persist in weaving and embrace my distinct design sensibilities have profoundly shaped my narrative. Years later, meeting Swedish tapestry artist Helena Hernmarck inspired me to further explore my artistic innovation and embrace the uniqueness of my creative expression.

SB & ZF: Your work references Indigenous Plains parfleche and Quechua weaving traditions. What are additional influences that resonate within your artistry? How is the conversation between these styles woven into your practice, specifically, your exploration of Native female abstraction from various cultures?

DB: I hold a profound appreciation for the artistry of parfleches from Indigenous Plains communities, drawn in by their structured compositions reminiscent of traditional Diné weaving. I am inspired by their contrasts and vibrant hues.

As for Quechua weaving, my interest in serapes and ponchos sparked a quest for knowledge as our community lacked individuals weaving such garments. My investigations led me to Peru, spending a month collaborating with local weavers and exchanging cultural techniques. Upon my return to Tsélání, I crafted a Diné rendition of the serape, hoping to inspire fellow Diné weavers to revisit and revitalize these traditional garments.

SB & ZF: Diné Bizaad is your first language. How has this influenced your weaving mentality and practice? Did you learn to weave in the language?

DB: Yes, Diné Bizaad is integral to my identity. The vocabulary within Diné Bizaad has terms that convey weaving techniques, processes, and tools, creating a connection to the foundational elements of my craft. Instructions and corrections were handed down in my first language, reinforcing the symbiosis between spoken language and artistic expression.

SB & ZF: Hózhó is often translated as “beauty, harmony, and balance.” Is this principle integral to your textile practice? Does it manifest in your design and color choices?

DB: Indeed, the phrase hózhó dólaá signifies a state of satisfaction with harmony and well-being. It roots my creative endeavors into daily rituals. The sacredness of my weaving space facilitates the flow of balance in the colors I choose and how patterns develop, seamlessly aligning with the ethos of hózhó.