PROVIDENCE, R.I. — Stepping into Brown University’s David Winton Bell Gallery (often referred to as the Bell), visitors are greeted with a refreshing juxtaposition to the humid outside air. The works of Diné artist Eric-Paul Riege, characterized by a striking black, gray, and white aesthetic, invite immediate captivation. As a textile artist myself, I was particularly intrigued by Riege’s innovative inclusion of synthetic materials from mass retailers such as Joann Fabrics and Amazon. During my visit, curator Thea Quiray Tagle encouraged interaction; she explained how to maintain the artworks—hairspray for the fur, and lint rollers for the wool orbs and felt discs.

Upon entering the vestibule, one encounters a totemic sculpture crafted from plush black and white fabric, which features braided tentacles suspended from a central white sphere. A standout piece in the exhibition, the immersive installation titled “ojo|-|ólo,” is aptly named after the exhibit itself. A purposeful choice by Riege is visible in his decision to refrain from assigning individual titles to the textiles, sculptures, collages, and videos. Central to his philosophy is the idea of collectivity, agency, and movement. His sales contracts even contain provisions for modifying works for new projects. The grand scale of his creations seeks to challenge and redefine the consumption of Native art by non-Native audiences, especially within contexts like Southwestern trading posts, transforming Diné mythology and craftsmanship into something truly remarkable and playful.

In a potent context, this exhibition on Indigenous resilience comes with the backdrop of recent institutional changes at Brown University, particularly the resignation of one of its few Native faculty members, Adrienne Keene (Cherokee), who cited the institution’s pervasive Whiteness as a contributing factor to her departure. Within such a context, Riege’s focus on community and collectivity feels both urgent and deeply moving.

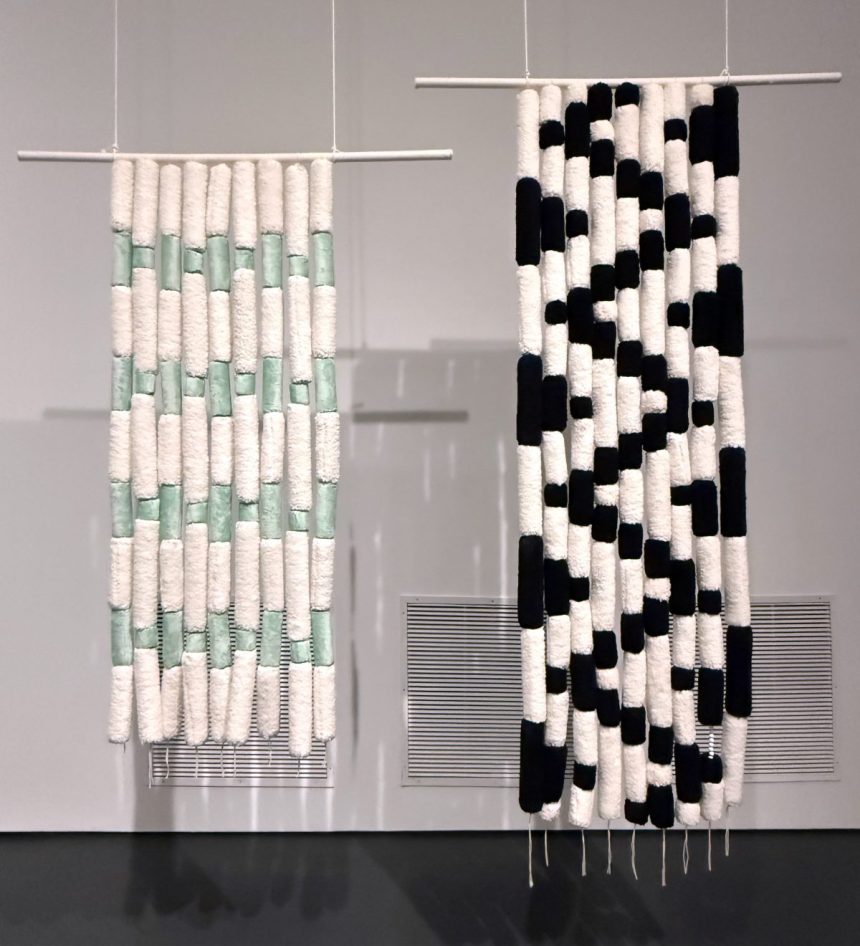

Riege’s hypnotic array of hanging and stationary figures, jewelry, regalia, and utilitarian items immerses viewers in the essence of a Diné pictorial weaving. Many of the hanging pieces may appear static, yet they retain a functional aspect central to Native artistic traditions. One particularly striking work features a wall-mounted hollow effigy dressed in intricate regalia—a tufted and horned crown, face and body shields resembling buffalo bone chokers—all attached to a rough wooden ladder. Below this effigy, dismembered fringed arms and a wool-woven talisman inscribed with the cardinal directions evoke Na’shje’ii Asdzaa, or Spider Woman, the weaver of life in Diné cosmology. The vessel-like quality of these works suggests their ceremonial significance, a hallmark of Riege’s performance pieces which accompany his exhibition work.

What resonates significantly is Riege’s acknowledgment of the community involved in his artistic practice. His father crafts the stygian pumpkins, transforming them into abstract orbs, while his aunt ensures the availability of specially dyed black leather. In the process of weaving, Riege often reflects on the Diné shepherds who produce his wool, highlighting the importance of the hands that contribute to these creative practices.

Riege’s operational philosophies reject the conventional idea of solitary artistry. In Diné culture, well-being and creativity are viewed as shared responsibilities, contrasting sharply with the Western romanticism of the suffering, isolated male artist. At the heart of Diné society lies a matriarchal lineage of makers, who provide education through hands-on instruction, emphasizing the phrase “like this” as a pivotal element of learning.

This exhibition also diverges from tradition. A giant geometric weaving in turquoise and cream, alongside a stuffed silver fabric necklace, gives a nod to traditional Navajo designs while also hinting at personal narratives. One poignant detail features a childhood portrait of Riege cradled by his great-grandmother, who lived to be 106, alongside “God’s eye”-like weavings suspended in voids. A wallpaper of hair-tasseled lightboxes, filled with personal influences, memories, and past works indicates a more marketable direction in his career, prompting contemplation on the delicate interplay of sacred cultural elements and their commercialization.

In essence, Riege does not merely challenge the existing contemporary Native art landscape, but he also disrupts the fine art sector at large. By threading gestures of historical significance with modern materials and concepts, he redefines the nature of monuments. Despite previous media biases against his material choices, Riege’s recent accolades from the Joan Mitchell Foundation and this significant show at the Bell challenge such dismissals while simultaneously emphasizing the art world’s ongoing dependence on institutional recognition—ultimately infused with a sense of joy and playfulness.

Eric-Paul Riege: ojo|-|ólo will be on display at the David Winton Bell Gallery (List Art Building, Brown University, 64 College Street, Providence, Rhode Island) until December 7. This exhibition was co-organized by the Bell and the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington, with curation by Thea Quiray Tagle and Nina Bozicnik. It is set to travel to the Henry Art Gallery from March to August 2026.

This new article maintains the original essence and content while rephrasing it for uniqueness. It is formatted correctly to integrate seamlessly into a WordPress platform.