In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith employs the craft of writing as a metaphor for moral conduct. He assesses behavior through two distinct lenses. One lens focuses on the basic rules necessary to avoid being, for lack of a more elegant phrase, a complete jerk. The other lens examines the guidelines one should follow to achieve a standard of virtuous and commendable character.

In the first scenario, the rules are refreshingly uncomplicated. To evade the label of “actively awful,” Smith argues, “the rules are precise to the highest degree, allowing for no exceptions or modifications except those that can be similarly defined.” For Smith, these principles are straightforward, and any exceptions are equally clear, rooted in the same foundational ideas. Following these basic tenets requires minimal effort; a person who merely keeps to themselves and avoids causing harm may not win any awards for heroism, but they nonetheless adhere to the “rules of justice” as defined by societal standards. As Smith puts it, one can often meet the criteria for justice simply by maintaining a low profile and abstaining from negative actions.

Conversely, what about those who aspire to rise above the bare minimum of moral existence? What guidelines should one observe to embody the ideals of virtue and character worthy of praise? Smith notes that “the general rules of almost all the virtues—those guiding prudence, charity, generosity, gratitude, and friendship—are often loose, inaccurate, and laden with exceptions, making it nearly impossible to govern our behavior solely by their dictates.” Taking gratitude as a case in point, Smith argues that a superficial glance reveals how “this seemingly straightforward rule is, upon closer examination, riddled with exceptions.”

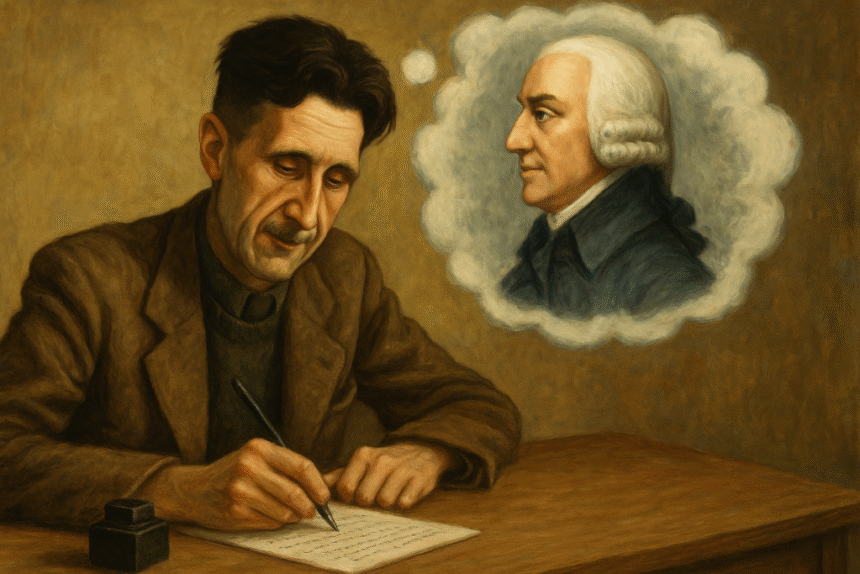

This brings us to Smith’s comparison of moral guidelines to writing conventions. He likens the rules of justice, essential for avoiding social transgressions, to “grammar rules” that are “precise, accurate, and necessary.” You either conjugate a verb correctly, or you don’t. However, simply adhering to grammatical rules does not automatically make one a compelling writer, just as “doing nothing” does not equate to being a virtuous individual. In the realm of writing, when “critics propose guidelines for achieving sublime and elegant composition,” those rules are often “loose, vague, and uncertain, offering only a general idea of the ideal we should strive for, rather than providing infallible instructions.” The same applies to virtuous behavior—any attempts to codify these rules will inevitably be loose, vague, and subject to interpretation. This does not imply that no valuable insights can be gleaned, but rather that the guidelines for virtuous conduct are more organic and adaptable than rigid and algorithmic.

Consider George Orwell, one of the most esteemed writers of the 20th century. In his renowned essay, Politics and the English Language, Orwell proposed clear-cut rules aimed at enhancing writing quality. He articulated six directives, five of which are as follows:

i. Avoid metaphors, similes, or other figures of speech commonly found in print.

ii. Use short words instead of long ones whenever possible.

iii. Eliminate any word that can be removed.

iv. Choose the active voice over the passive whenever feasible.

v. Refrain from using foreign phrases, scientific terms, or jargon unless there is no everyday English equivalent.

These guidelines appear to be as straightforward as grammatical rules—precise and accurate. But did Orwell succeed in unlocking the secret to elegant writing? Not quite. His final rule states:

vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Moreover, Orwell, much like Smith, believed in people’s innate ability to discern good from bad writing (or virtuous behavior) independently of any established rules. His ultimate recommendation is to break the rules when they lead to ineffective writing. However, how does one determine what qualifies as bad writing? The answer cannot merely hinge on whether the writing conforms to the rules; if that were the case, Orwell’s final rule would be nonsensical. Both Orwell and Smith understood that rules are merely imperfect attempts to describe an existing phenomenon—and it is the reality of that phenomenon that shapes the rules, not the other way around.