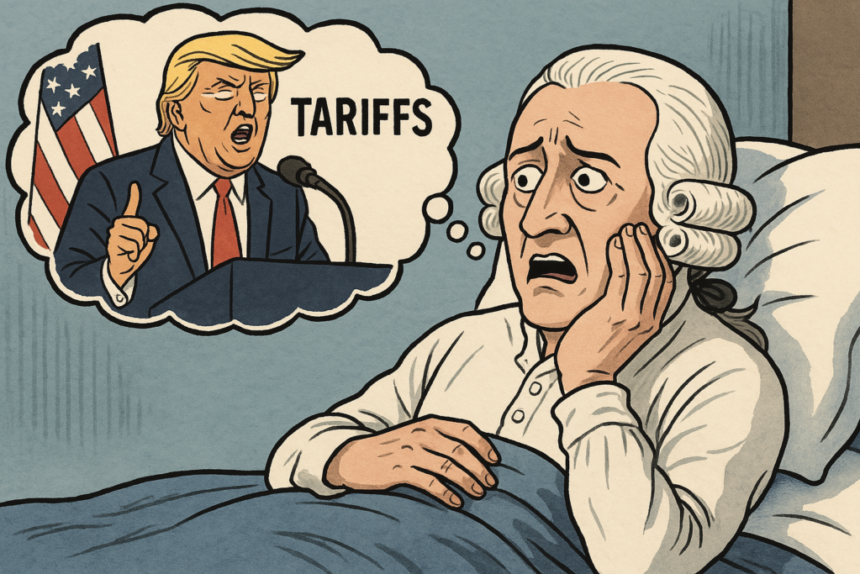

Recently, someone inquired about the ramifications of the world descending into a trade war due to the tariffs announced in the Rose Garden. I jokingly remarked that either Adam Smith would be proven incorrect or we would all find ourselves poorer. This notion holds true even with the reduced tariffs, which still see American tariffs soaring higher than they have in a century.

In response, as is often the case, they referenced Adam Smith’s rationale for tariffs, drawn from Book 4, Chapter 2 of Wealth of Nations. However, these arguments are a distraction, as we shall explore. Let’s examine how they apply to our current situation.

Smith identifies two scenarios where managing trade can be justified: firstly, in shipping, due to its connection to military defense, and secondly, by imposing taxes on imports equal to those on domestic goods to ensure fair competition. Furthermore, trade restrictions should not be outright condemned when (A) they are retaliatory tariffs or (B) when transitioning towards free trade.

So, what’s the fuss? Retaliatory tariffs are indeed on the list. Why would the Rose Garden tariffs irritate Adam Smith?

Smith explicitly outlines the conditions under which retaliatory tariffs are acceptable. He states, “There may be good policy in retaliations of this kind, when there is a probability that they will procure the repeal of the high duties or prohibitions complained of.” (IV.ii.39) In simpler terms, retaliatory tariffs are justified only if they lead to freer trade. Israel’s recent removal of tariffs against the United States did not protect them. Similarly, when Vietnam and the European Union proposed eliminating all tariffs, the administration dismissed these offers as inadequate. If these were meant to be retaliatory, they have utterly failed.

However, the Rose Garden tariffs were never truly retaliatory. They did not arise from how much other countries impose tariffs on the United States, nor were they influenced by non-tariff barriers. The White House confirmed that the tariffs were calculated using the trade deficit divided by U.S. imports from that country, further divided by two (unless a country maintains a trade surplus with the U.S., in which case the tariff was set at 10%).

This indicates that the focus is not on retaliation but, at best, on a negative trade balance. And we all know what Adam Smith thought about the balance of trade, don’t we?

“Nothing, however, can be more absurd than this whole doctrine of the balance of trade, upon which, not only these restraints, but almost all the other regulations of commerce are founded. When two places trade with one another, this doctrine supposes that, if the balance be even, neither of them either loses or gains; but if it leans in any degree to one side, that one of them loses and the other gains in proportion to its declension from the exact equilibrium. Both suppositions are false.” (WN IV.iii.a)

In truth, Adam Smith’s arguments regarding tariffs serve as a red herring when it comes to understanding his perspective on these tariffs.

The announcement of the tariffs from the Rose Garden did not merely hike the costs of international trade. As Thomas Sowell noted, this declaration also incited uncertainty, making foreign investment and globally integrated supply chains more precarious—riskier—just as the tariffs themselves elevate the costs of international trade. The cumulative effect of these policies is akin to the impact of all trade restrictions: they contract the global market. Transactions that would have been economically viable become prohibitively expensive and simply don’t occur.

At the heart of Adam Smith’s economic philosophy is the idea that the wealth of nations springs from the division of labor (Book 1, Chapter 1), a process made possible by our innate tendency to truck, barter, and exchange (Book 1, Chapter 2). This division of labor is constrained by the number of individuals among whom labor can be divided, a concept Smith refers to as the “extent of the market” (Book 1, Chapter 3).

Therefore, if we believe that the tariff announcement in the Rose Garden will not lead to a decline in our overall wealth due to the reduction in potential trades—and thus a shrinking market—then we must conclude that the division of labor is not the source of national wealth. If the Rose Garden tariffs do not result in a poorer society, then Adam Smith must indeed be mistaken about everything.

And if Smith was wrong about everything, why should we take his views on tariffs seriously?

Related content:

CEE Entries: Protectionism, Mercantilism

WealthofTweets: Book 4, Chapter 2

WealthOfTweets: Book 4 Chapter 3

Jon Murphy, The Political Problem of Tariffs