Fiery particles of burning wood dance through the smoky atmosphere, targeting an unsuspecting home. In front of the single-story dwelling, these glowing bits, each only a few centimeters in diameter, appear inconsequential. Yet, each airborne ember carries the potential for devastation. Researchers believe that embers account for approximately 60 to 90 percent of home ignitions.

A trash can sits adjacent to the house, its cover ajar with cardboard strewn inside. The fiery particles infiltrate and flames rapidly emerge. Moments later, a blaze shoots up the side of the house. The vinyl siding begins to blister and twist, while burning debris plummets to the ground, and a crackling, smoldering fissure creeps upward. The flames, with hues of orange, blue, and purple, leap towards the roof.

A sharp hiss resonates as firefighters approach to douse the fire. Their actions are part of a planned demonstration. The flaming building is merely a facade of a real house, as if an enormous butcher has severed a clean slice of exterior wall. This controlled fire scenario is taking place at the National Fire Research Laboratory in Gaithersburg, Maryland.

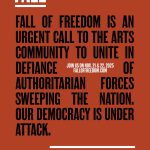

Burned bins

After a wildfire in Los Angeles in January, all that remains of a trash bin is a melted puddle (top). Meanwhile, at the National Fire Research Laboratory in Gaithersburg, Md. (bottom), scientists examine how trash bins contribute to fire spread.

Many of the deadliest and most damaging fires in modern memory have occurred amid these conditions.

As fire-prone areas continue to grow worldwide, climate change is extending and intensifying fire seasons. The combination of these circumstances and fierce winds capable of pushing embers over distances of kilometers can overwhelm communities.

“Controlling wildfires becomes ineffective under extreme conditions,” states Jack Cohen, a retired fire scientist from the U.S. Forest Service who has devoted years to studying fire behavior in wildland-urban interfaces. Instead, the emphasis should shift toward adapting communities to withstand fires, he asserts. “This isn’t just a wildland issue; it’s an issue of how structures ignite.”

For years, Maranghides and fellow researchers have been focused on enhancing community resilience. Their work has led to guidelines like the Hazard Mitigation Methodology (HMM) from NIST, first published in 2022, which identifies a range of weaknesses and strategies to mitigate them. It emphasizes the collaboration needed for fire resilience, especially in closely packed neighborhoods.

This is critical because a burning house can ignite nearby structures within about 50 feet. Hardening just some homes in such areas fails to protect all. “An ignited home poses a grave threat to its surroundings,” Maranghides explains. Every structure must be fortified to ensure the safety of the entire community.

The real challenge lies in motivating every resident to participate in community hardening efforts. Guided by NIST’s principles and similar frameworks, initiatives for comprehensive community hardening have begun in certain Western regions. There’s a consensus that society must learn to adapt to living with wildfires, as long as residents insist on living in susceptible areas. Cohen emphasizes, “While wildfires are inevitable, widespread community devastation does not have to be.”

Insights from disaster

On November 17, 2018, a group of NIST researchers headed to California’s Sierra Nevada foothills to analyze the state’s most devastating fire. Just over a week prior, katabatic winds had snapped a power line, setting off a blaze in the Feather River Canyon, a steep waterway.

By nightfall, the fire had devastated the towns of Concow, Paradise, and Magalia, destroying over 18,000 structures, damaging 7,000 others, and claiming 85 lives. Much of the Camp Fire’s spread was airborne; winds carried embers for kilometers, igniting new fires long before the main fire front arrived. “It spreads like hopscotch,” details Steve Hawks, a wildfire researcher and seasoned firefighter with 30 years at CAL FIRE. “The main fire front eventually follows but lags behind.”

The NIST team arrived during active flames and spent four days collecting data, interviewing meteorologists and first responders. Dozens of deployments followed over the next half-year. Various sources, spanning from fire truck logs to evacuation data, were analyzed. After over six years of evaluation, NIST’s initial report on the Camp Fire was published in 2023, with another set for 2026.

Basing their reports on exhaustive data collection, the WUI Fire Group at NIST has conducted only four fire case studies. “It’s like CSI for communities,” Maranghides describes. Observations from the field direct NIST’s research in the lab. For example, they discovered that fences acted as conduits for fire, leading to studies on the influence of fence materials and designs on fire spread. Additionally, they found that storage sheds igniting could cause flames to reach nearby residences, aiding research that concluded wooden or steel sheds should be located at least 4.5 meters from homes. “A shed can create fire jets through its openings when it catches fire,” notes Maranghides.

NIST also conducts experiments examining how various materials ignite and spread flames between structures. These investigations reveal critical conditions under which vulnerabilities transform into real hazards, leading to updates in NIST’s framework for fire-adaptive communities—the Hazard Mitigation Methodology (HMM).

Embers beware

- Install noncombustible skirting around decks to prevent ignition underneath.

- Utilize dual-paned tempered glass windows with noncombustible frames to reduce the chances of breaking or burning. Adding a metal window screen offers extra protection.

- Fit fine metal mesh with ⅜ inch openings behind vent covers to block embers from entering attics.

- Employ noncombustible fencing that is at least 2.5 meters (8 feet) away from the house.

NIST’s methodology integrates tactics to fortify communities against wildfires. The first strategy concentrates on strengthening structures against flames with durable designs and materials. For example, metal siding could reinforce the lower sections of walls. The second strategy focuses on reducing exposure to flammable items near homes, such as furnishings, plants, or vehicles.

Although the HMM may resemble standard fire codes, it acts more like a “code plus,” Maranghides argues. Instead of only addressing individual properties, the methodology promotes community-level efforts since fire doesn’t recognize property boundaries.

“Your home might be perfectly prepared, but all neighboring properties must be equally equipped,” emphasizes Michele Steinberg, director of wildfire division at the National Fire Protection Association in Quincy, Mass., an organization committed to developing fire safety regulations.

Every vulnerability in a community requires attention for effective resilience. In areas with homes located within 15 meters of one another, an ember could ignite one house, triggering a destructive chain reaction as flames jump from building to building. “When bombarded by a million embers, they will inevitably locate vulnerabilities,” warns Maranghides. “You cannot simply partially implement ember-resistant measures.”

Several existing fire protection recommendations overlook vulnerabilities highlighted by NIST. Maranghides points out that approximately 75 percent of ember vulnerabilities and 50 percent of flame vulnerabilities in the HMM are absent from fire codes in California, the National Fire Protection Association, and the International Code Council, a Washington D.C.-based organization that produces safety standards. “Codes alone aren’t sufficient.”

Deflecting fire

- Even if a shed is safely distanced from a home, it could threaten the community if positioned too close to a neighboring residence.

- During heightened fire risk, relocate vehicles at least 30 feet away from homes.

- Remove flammable items from decks or replace them with safer metal outdoor furnishings.

- Establish a 1.5 meter (5 feet) perimeter around your home devoid of combustible materials, including wooden furniture, trees, and trash cans.

A comparable strategy to NIST’s is the Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood Standard, developed by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety, a nonprofit organization supported by property insurers and based in Richburg, S.C.

This institute conducts fire experiments and on-site studies of wildland-urban interface fires, yielding results that often corroborate NIST’s findings. For example, while inspecting the aftermath of the Palisades Fire, Hawks and his team saw plastic trash bins with melted holes, indicating that embers could still penetrate even closed containers. They also observed damaged melted bins located near burned structures. “We noted extensive damage stemming from the bins where embers landed,” recalls Hawks, the institute’s senior director for wildfire. The institute advises homeowners to move bins at least 30 feet from their homes during significant absences and during Red Flag warnings, alerts that indicate heightened fire risks due to dry and windy conditions.

While numerous measures in the Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood standard align with or are derived from NIST’s work, the institute takes an additional step by certifying homes and communities that meet the established criteria, according to Hawks. This certification could assist individuals in securing homeowners’ insurance, particularly as insurers in California and other states withdraw thousands of policies due to more frequent and costly climate-related disasters.

Earlier this year, developers introduced a new community in Escondido, California, called Dixon Trail. This development is the inaugural community to receive the Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood designation from the insurance institute. Each residence is insured, despite the challenging insurance landscape in California.

Visitors to Dixon Trail might overlook the fire-resistant features, such as enclosed eaves that deter embers, dual-paned tempered glass that withstands high temperatures, and noncombustible fences. However, the five-foot buffer around each home, clear of flammable materials like mulch, furniture, or plant life, stands out.

As robust as the research is, “its effectiveness hinges on practical implementation,” Steinberg observes. The pressing question remains, “How do we achieve this?”

Applying science at the local level

While the Dixon Trail development serves as a model, the most significant opportunity to safeguard communities is through retrofitting existing homes.

Approximately 130 kilometers north of San Francisco lies Clear Lake, California’s largest natural freshwater lake, surrounded by two cities, several small towns, and numerous oak trees. Fire is a recurring threat in this area. Just three months ago, the Lake Fire consumed 401 acres near Clear Lake’s eastern shore.

“Pretty much everyone here has faced the trauma of fire, whether being evacuated or losing their homes,” recounts Deanna Fernweh, a lifelong Lake County resident. “It feels like an ongoing crisis we can’t escape.”

On the southern shore of Clear Lake sits Kelseyville Riviera, a newly established community comprising about 1,500 homes and 3,400 residents. Coordinated through the California Wildfire Mitigation Program, a state-led initiative that collaborates with FEMA and local organizations, the goal is to assist residents in retrofitting their homes for fire resilience, informed by the HMM, California’s building code, and fire resistance tests from CAL FIRE.

Selection criteria for communities focused on susceptibility to wildfire and the impact of climate change, as well as residents’ characteristics, including age, disability status, poverty level, lack of transportation, and language barriers.

Lake County has been selected for the initiative, and Kelseyville Riviera has been classified as an area with heightened risk. “Dense vegetation surrounds the neighborhood, which has limited access and narrow roads,” reports Fernweh, who is also the program manager for North Coast Opportunities, the nonprofit leading the relocation project. “Many lots are cramped, with some homes just 25 feet apart. Fire spreads from rooftop to rooftop,” she emphasizes.

Collaborating with local organizations for home retrofits carries many advantages. “It’s much easier to discuss these issues with a neighbor than have a representative come from Sacramento,” says J. Lopez, the executive director of California Wildfire Mitigation Program. “More importantly, this builds local knowledge capacity.”

The initiative is still in its early stages. To date, at least 30 homes in Kelseyville Riviera have undergone retrofitting, part of a total of 70 completed statewide. An additional 200 homes have been assessed or are in the process of retrofitting, with hundreds more applications pending. Retrofitting costs range from about $36,000 to $110,000 depending on the location.

Lopez hopes that the project will scale as it progresses beyond the pilot phase. In 2028, the California Wildfire Mitigation Program Authority will present a report detailing the initiative’s costs, challenges, and objectives to the California legislature, aiming for permanent establishment of this project.

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau indicates that homes built from 2020 to 2022 constitute only 2 percent of owner-occupied residences, highlighting the urgent need for retrofits. However, engaging individuals can be a challenge, particularly if they bear the financial burden, Steinberg notes. “Collaboration is essential, along with policy and practice changes at every level, from national to local.”

This alignment may take time. “No single entity—federal, state, local, public, or private—holds complete authority over this issue,” states Frank Frievalt, director of the Wildland-Urban Interface Fire Institute at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo.

Meanwhile, Frievalt encourages individuals to refer to NIST and the Insurance Institute’s guidelines. “Don’t idle waiting for local authorities, insurers, or fire inspections,” he advises. “Take initiative to secure your property. The aim is survivability, not just insurability.”

Encouragingly, the challenges posed by wildfires in the wildland-urban interface are solvable. Yet, “transformation won’t occur overnight,” Maranghides cautions.

He envisions a time, a generation from now, when a wildfire encounters a community and simply fizzles out.

In comparison to earthquakes, tornadoes, and other natural hazards, fire may be among the phenomena most amenable to mitigation. “In a tornado, energy lies in the atmosphere,” notes Maranghides. “Here, the energy resides within the community.”