A recent analysis contends that the narrative around housing affordability may be more nuanced than it seems when considering factors like size, quality, and the growth of household incomes. Indeed, while the sticker price of homes has escalated, they have also become notably larger and more luxurious, and households, on average, are earning more.

However, we must recognize the genuine housing affordability crisis facing working- and middle-class families in various metropolitan regions. According to Bankrate, the income required to comfortably afford a median-priced home in the U.S. surged by 50% since 2020, now standing at $117,000.

The economics behind housing affordability is rather straightforward: if prices are climbing, it’s either due to a surge in demand, a decrease in supply, or a cocktail of both. While supply limitations are the primary offenders in this affordability conundrum, it’s crucial to acknowledge that buyers have also played a role in the market dynamics; after all, it takes two to tango. Housing functions as a normal good with a long-run income elasticity of demand close to one, meaning that as household incomes rise, so too does the demand for housing.

To effectively lower prices, builders must increase the housing supply “out and right” at a greater rate than buyers are shifting the demand curve. Builders are acutely aware of the necessary changes: reducing restrictive zoning laws (especially for multifamily units), streamlining licensing and permitting processes, relaxing building codes and energy standards, fostering freer markets in labor and materials, and perhaps, cultivating a consumer willingness to embrace smaller, simpler homes.

Drawing from our experiences in home building and economic analysis, we identify three critical drivers of housing unaffordability: zoning laws, building codes, and the increasing size of homes.

Virtually all jurisdictions in the U.S. enforce zoning regulations that severely restrict the number of new homes that can be constructed. In the quest for safety and energy efficiency, more stringent building codes necessitate pricier construction methods and materials. Consequently, builders have largely abandoned modest starter homes in favor of sprawling “McMansions.”

Zoning: An Obstacle to Affordable Housing

Economists widely agree that zoning restrictions are among the most significant impediments to housing supply growth. Urban planner-turned-anti-zoning advocate Nolan Gray delivers a compelling critique of zoning in his book Arbitrary Lines (which received excellent reviews from David Henderson). Gray elucidates how zoning inflates housing costs:

Zoning restrictions block new housing developments, either by prohibiting affordable housing altogether or by enforcing density limits. This results in fewer homes being built, leading to the supply and demand mismatches evident in most U.S. cities today. Furthermore, zoning compels the homes that do get constructed to adhere to higher quality standards than residents may actually need, due to policies such as minimum lot sizes and parking requirements. Additionally, zoning adds an unpredictable layer of review to the permitting process, further raising housing costs. (p. 52–53)

There is ample evidence supporting the notion that zoning significantly constrains housing supply and inflates prices. Take Houston, for instance, a standout example of a large city without zoning. Its lack of zoning allows for a flexible housing supply, which reacts swiftly to price changes. As Gray points out, “Houston builds housing at nearly three times the per capita rate of cities like New York City and San Jose… in 2019, Houston constructed approximately the same number of apartments as Los Angeles, despite the latter being nearly twice its size.” (p. 144) This responsive supply elasticity in Houston enables the housing stock to expand alongside demand, thereby keeping price hikes in check. For large urban centers, Houston ranks highest in affordability when comparing median home prices to median household incomes.

Building Codes: An Inflationary Force

Following a family tradition that began with our grandfather in 1948, we constructed several spec homes in 2005–2006, enjoying substantial profits until the subprime mortgage crisis derailed our success.

After nearly a decade away from the business, Joel resumed building, while Tyler pursued a career in academic economics. Upon visiting one of Joel’s new projects, Tyler observed that exterior walls had transitioned from the traditional 2x4s to 2x6s, a change mandated by evolving building codes focused on enhancing energy efficiency. This shift exemplifies a broader trend of increasingly stringent requirements aimed at marginal improvements in safety and efficiency.

A series of studies commissioned by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) estimated the financial impact of specific modifications to the International Residential Code (IRC) on home construction. These studies revealed that from 2009 to 2018, code changes increased construction costs for typical homes by approximately $13,225 to $26,210. Given the ongoing updates, the IRC has the potential to perpetually escalate costs.

Another NAHB study found that government regulations—including zoning, building codes, design, and safety—accounted for nearly 24% of the sales price of a new single-family home—amounting to $93,870 based on the median new home price in 2021.

Small + Simple = Affordable

Homes in the U.S. have dramatically increased in size since the heyday of affordable housing in the 1950s and 1960s. The average home size swelled from 1,500 square feet in 1960 to a peak of 2,700 square feet in the mid-2010s. Today, new homes average around 2,400 square feet, and the construction of small starter homes has nearly vanished.

Homes less than 1,400 square feet, once predominant, now account for less than 10% of new constructions, despite a significant reduction in household sizes since 1960.

;

Advocates for improved affordability should champion smaller, simpler homes—true starter homes. With the 2024 national average construction cost of $195 per square foot (excluding land), today’s 2,400 square foot home costs over $200,000 more to build compared to a 1,200 square foot starter home. By eliminating high-end features like granite countertops and premium appliances, we estimate that site-built homes around 1,200 square feet could be constructed and sold profitably for $100,000 less than the current national median price, which hovers around $410,000, even in the most expensive metropolitan areas.

So why aren’t more builders focusing on producing smaller, basic homes to satisfy the pressing demand for affordable housing? The answer lies in the substantial regulatory cost burden—particularly from zoning and building codes—which renders starter homes unappealing for both buyers and builders.

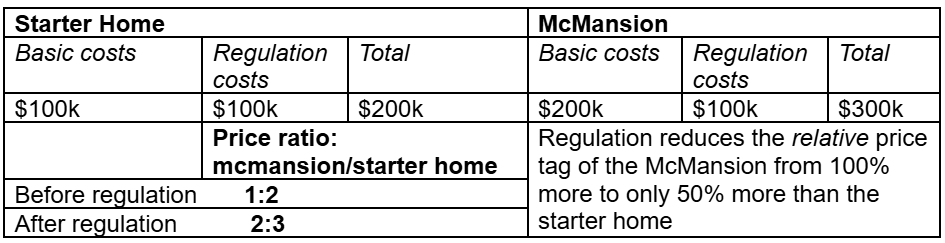

To illustrate, let’s compare the costs of a hypothetical 1,200 square foot starter home with that of an opulent 2,400 square foot McMansion. If we assume regulatory costs add up to $100,000 per home, basic construction expenses are, generally speaking, directly proportional to home size and quality. Consequently, in a less regulated environment, a 2,400 square foot home would logically cost about double that of a 1,200 square foot home (not accounting for land costs). However, the impact of stringent regulations does not scale with home size and quality; rather, it represents a fixed expense applicable to any home size. Thus, while regulatory compliance adds a similar financial burden to both the starter home and the McMansion, it effectively narrows the price gap between the two, making the latter more attractive relative to the former. Economists refer to this phenomenon as the Alchian-Allen Effect.

In a deregulated scenario, a starter home could be priced at half of that of a McMansion. But once regulatory costs are factored in, the starter home might only be priced at two-thirds of the McMansion’s cost. As regulatory costs escalate, the relative price of larger, more lavish homes declines, consequently discouraging builders and buyers from pursuing comparatively pricier starter homes.

Embracing “Low Quality” Goods

The late Walter Williams, our beloved economics professor, famously asserted, “Low quality goods are part of the optimal stock of goods.” This statement holds true—how else can we meet the material needs of those with limited means? Williams did not advocate for unsafe or non-functional products, but rather for those designed with cost efficiency in mind. In terms of housing, this translates to smaller and simpler homes.

To foster a robust supply of lower-quality goods, governments must eliminate burdensome taxes and regulations that make it difficult for entrepreneurs to succeed in the low-end marketplace. Unfortunately, many lower-income individuals seeking shelter have been priced out of the market due to these regulations.

To ensure a consistent flow of affordable housing, governments need to significantly reduce the cost-prohibitive rules and restrictions imposed by zoning and building codes. The adage “If you build it, they will come” resonates strongly here, and let us be clear: affordable homes won’t materialize until governments alleviate the excessive regulatory burdens currently in place.

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics at Ferris State University, while his brother Joel Watts is a homebuilder.