Study Shows Bilirubin Could Protect Against Malaria

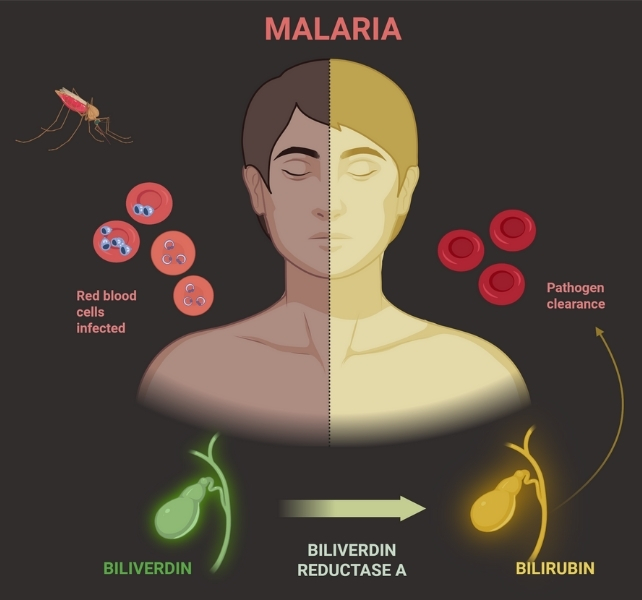

In cases of jaundice, a condition where bilirubin turns a person’s skin and eyes yellow, it is traditionally seen as a sign of liver malfunction. However, a recent study suggests that bilirubin build-up may actually play a protective role in individuals with malaria.

According to Johns Hopkins molecular biologist Bindu Paul, who led the study, “Bilirubin was once considered to be a waste product. This study affirms that it could be one critical protective measure against infectious disease, and potentially neurodegenerative diseases.”

Each year, over 260 million people in tropical and subtropical regions are infected with malaria, a disease transmitted through the bite of an Anopheles mosquito carrying the Plasmodium falciparum parasite. The disease claims around 600,000 lives annually.

The parasite invades red blood cells, causing them to burst and release iron-rich heme, which can be toxic in high concentrations, affecting disease severity. The study found that bilirubin, produced through a chemical reaction, offers protection against this iron-induced damage.

In individuals with malaria, jaundice is sometimes present, but its impact on the disease outcome was previously unclear. The research team discovered that asymptomatic individuals had significantly higher levels of unconjugated bilirubin in their blood plasma compared to symptomatic individuals, suggesting a protective role.

Mouse experiments further elucidated the protective mechanism of bilirubin against malaria. Mice lacking bilirubin were more susceptible to the parasite, while normal mice with elevated bilirubin levels survived the infection. Bilirubin was found to inhibit the growth and survival of the Plasmodium parasite within red blood cells.

The team concluded that bilirubin production in response to Plasmodium infection is an evolutionary defense mechanism against malaria. While this strategy may have benefits in fighting the disease, it can also lead to neonatal jaundice, which poses risks to brain health.

Paul and her team are optimistic that understanding this natural defense mechanism could lead to new strategies for mitigating the impact of malaria on global health. The study was published in the journal Science.