Intro. [Recording date: December 9, 2025.]

Russ Roberts: Today is December 9th, 2025. Before I introduce our guest, let me remind you to cast your vote for your favorite episodes of 2025 by visiting econtalk.org. You’ll find a link to our survey there. Thanks for tuning in!

My guest today is Anna Gát, the founder and CEO of Interintellect, an intriguing platform for open intellectual and political conversations. This platform gathers attendees, community members, and event hosts to explore the most pressing ideas of our times. Anna is also the host of the podcast The Hope Axis and contributes to Substack with her writing at American Innocence. Welcome to EconTalk, Anna.

Anna Gát: Thank you for having me! I’m thrilled to be here.

Russ Roberts: Today, we’re diving into the topic of culture and the purpose of your fascinating platform, Interintellect. Along the way, we’ll also pay tribute to Tom Stoppard, who passed away last month, and his play Arcadia, which happens to be my favorite modern play—perhaps my favorite of all time. I’ve seen it three times and hope to catch it again. But first, let’s start with Interintellect. I’ve participated in it and found it quite enjoyable. Could you explain to our listeners what it is and what motivated you to create it?

Anna Gát: Absolutely! I remember your episode hosted by Bronwyn Williams, the South African economist, when you discussed your book Wild Problems from 2022, which I thoroughly enjoyed and often recommend. If I know someone is particularly troubled, I might gift it to them at Christmas with a little wink-wink, “Just read this.”

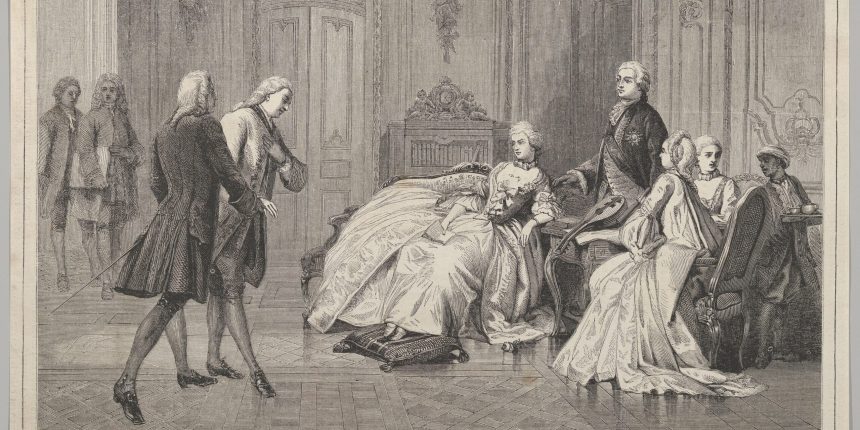

I founded Interintellect in 2014 while pursuing my third master’s degree in theater in London, which, as you can tell, reveals my penchant for unconventional life choices. I began studying academic-level classics at 19 in 2002 and was always involved in special programs at school, surrounded by great philosophers. Growing up in a showbiz family where screenplays were the norm, I found it fascinating to explore how different cultural perspectives—Greek, Enlightenment, German, French, and later Romantic—shaped the art of dialogue.

Yet, I was puzzled by the fact that storytellers, from Aristotle onward, had mastered the art of crafting dialogue—almost scientifically—while the same effort wasn’t applied to fostering real conversations among people. This frustration peaked around 2015-2016 when I sensed a growing inability among humanity to communicate effectively.

Every generation has its doomsday fears, believing that they are the last before civilization crumbles. It’s a comforting thought. So, I transitioned from writing plays to constructing spaces where real human interactions could occur. How can we format these interactions without stifling their essence? It became clear to me that people must bring their true selves to the table; otherwise, it wouldn’t be a conversation at all. My journey led me to create Interintellect, and I was pleasantly surprised by how technology could facilitate these discussions and how theatrical elements could be applied to real-life encounters.

Russ Roberts: Before we delve into the online aspect, let’s take a moment to discuss conversation itself.

Anna Gát: Let’s meta-converse about conversation!

Russ Roberts: Exactly.

Anna Gát: Let’s go meta!

Russ Roberts: I often ponder your earlier point: we don’t teach our children how to have conversations. More pointedly, it seems we fail to teach them how to listen. What we often impart is simply the notion of not talking when someone else is. Many people struggle with this; interruptions are all too human. The challenge lies in truly absorbing what the other person is saying, rather than merely formulating your response while they speak. What insights do you have about fostering better conversations, especially in a physical setting like a dinner party?

Anna Gát: It’s fascinating that you mention listening. Coming from an Eastern European Jewish background, where interruptions are the norm—think of a Robert Altman film where everyone speaks simultaneously—it’s enlightening. We often conceive one-on-one conversations as optimal units of exchange. Yet, research in conversation science reveals that setups where individuals face each other can actually create a sense of opposition, especially when delivering bad news, like a difficult medical diagnosis.

Physical dynamics in conversation matter. For example, even on Zoom, people tend to look away when thinking. Creating diagonal arrangements in conversation can ease tension. In any interaction, a host—a figure of temporary authority—can facilitate dialogue. The host’s role is to guide the conversation without imposing their views, ensuring everyone has a voice. This dynamic fosters more productive exchanges as it introduces a third perspective.

Moreover, when two individuals engage in conversation, they often circle back to the same points without a third party to steer them toward new insights. This is why involving additional participants can create richness in discussions.

Russ Roberts: You make an excellent point about shared visions in conversations. Sometimes, rather than making direct eye contact, we can better process our thoughts when gazing at a shared view, like a sunset or the activity of children playing. It’s interesting how vulnerability plays a role; looking into someone’s eyes can feel exposing when we’re deep in thought. Our natural instinct can be to look away.

Additionally, in many conversations, the roles are often predetermined. When a friend reaches out for support, the expectation is clear: one person listens, while the other shares. With different friends, I might be the teacher or the jokester, adapting to the role needed. This fluctuating dynamic can make conversations challenging and nuanced.

Anna Gát: That’s an intriguing perspective. In the U.S., I sometimes hear people ask, “Do you need me to listen or offer advice?” which feels overly clinical. It strips away the spontaneity of human interaction. People don’t want to feel like they’re acting; they seek authenticity in conversation. I’ve noticed that friends sometimes expect me to host when I attend their gatherings, and I find it amusing. Hosting is my profession, and when I’m off the clock, I’d prefer to simply be present.

Interestingly, the word ‘tribe’ derives from ‘three,’ suggesting that two participants often find tension, whereas a group of three can alleviate that. It’s a phenomenon I’ve observed in social settings—two people can easily fall into a cycle of disagreement, while a third person can help navigate the conversation.

Russ Roberts: Let’s return to Interintellect. Could you elaborate on the various offerings available on the platform?

Anna Gát: Certainly! Interintellect represents my experiment in facilitating large-scale conversations free from the toxicity often associated with cultural polarization. Over the past six and a half years, we’ve organized tens of thousands of events, effectively avoiding toxic exchanges.

We present conversations as a form of entertainment. Participants come to connect with new ideas and people, recharging themselves in the process. The platform aims to bring together diverse groups—be it Americans and foreigners, left- and right-leaning individuals, or those from STEM and humanities backgrounds. The ability to discuss pressing societal issues is vital, and we approach this with a playful spirit. By engaging in discussions about great literature, movies, and scientific discoveries, participants relax and find common ground.

Interestingly, many deep and meaningful relationships have blossomed from these interactions, leading to collaborations, marriages, and even families moving abroad together. It creates a generative atmosphere.

Russ Roberts: What is the typical size of these interactions?

Anna Gát: The size can vary quite a bit. For instance, I’m attending a dinner tomorrow with about 10 participants, discussing gastronomy and the immigrant experience in America. We also host larger events—like Bloomberg Beta’s book talks, which can attract up to 300 people. However, I prefer a more intimate setting of around 20 to 25 participants. This size allows everyone a chance to contribute meaningfully without feeling overwhelmed.

Russ Roberts: In those larger sessions, how do you manage the format? If you have a guest author, for instance, it might feel more like a lecture than a conversation.

Anna Gát: Indeed, that’s a valid point. The salons are designed to mimic the size of a living room, fostering a comfortable atmosphere for dialogue. The format started in 2019, originally taking place in living rooms around the world, and has expanded globally. When hosts list an Interintellect salon, they can specify the format, whether it’s a talk or a discussion group. I encourage hosts to communicate clearly with attendees about the nature of the event, ensuring everyone knows what to expect.

Russ Roberts: How do you address challenging participants? In a personal setting, it’s easier to decide whether to invite someone back, but how do you manage that in your events?

Anna Gát: Surprisingly, this issue arises infrequently because our format discourages disruptive behavior. Attendees typically pay for their participation, whether through a membership or a ticket. This intentional commitment fosters focused and respectful interactions.

In online events, I can mute participants if necessary. I advise my hosts to follow a priority structure: Facilitate, Moderate, Mediate. Facilitation is about creating a relaxed atmosphere; moderation steps in when disagreements arise, and mediation is rarely needed if the host maintains a strong presence. In my experience, I’ve only had a couple of instances of domineering behavior, which I managed by redirecting the conversation.

Russ Roberts: Have you seen improvements in your hosting skills over time?

Anna Gát: That’s a thought-provoking question. Perhaps my experiences have made me harder to surprise, but I also find it challenging to feel deeply passionate as I once did. Like any performer, I’ve developed routines. I often tell my team that we want a company where magic is an everyday occurrence, but that can also lead to routine.

Russ Roberts: You offer both online and in-person salons, correct? Are there other initiatives listeners should know about?

Anna Gát: Yes, our offline events are generally for members only, focusing more on community-building than the marketplace of ideas. We occasionally host larger festivals where intellectuals gather for multiple discussions throughout the day. Additionally, I produce a podcast called The Hope Axis, which tackles the theme of hopelessness in the American discourse, and I recently launched a Substack, American Innocence, where I share reflections on my cultural experiences in America and work on my upcoming book.

Russ Roberts: Let’s shift our focus to Tom Stoppard. I’ve long admired his work, and he’s on my list of dream guests, along with others like Mark Knopfler and J.K. Rowling. Sadly, he has passed away. Could you share what you’re doing with Arcadia? Is there an upcoming event in December or January?

Anna Gát: Yes, we’re hosting a reading of Arcadia on December 27th.

Russ Roberts: By the time this airs, it will have already occurred. Can you tell us more about the event and your previous experiences with similar readings?

Anna Gát: About four years ago, I proposed the idea of hosting online play readings, and the community embraced it enthusiastically. We’ve previously read Arcadia, Uncle Vanya, Much Ado About Nothing, and A Streetcar Named Desire, all with great success. The readings provide a unique opportunity for participants, some of whom discover acting ambitions and pursue them in school.

This second reading of Arcadia will feature the same actress who previously played Thomasina, now taking on the role of Lady Croom, marking a kind of coming-of-age for our group.

Russ Roberts: I have my own copies of Arcadia, and I can relate to your emotional connection to the play. It’s about many themes, which is why it resonates deeply. I remember the ending vividly—two couples dancing, one from modern times and one from the 1800s, sharing the same stage in a way that evokes profound emotional responses.

When I saw it again, I anticipated that moment, but the production differed, and it didn’t unfold as I remembered. The director had made a choice that altered the emotional resonance. It’s fascinating how different interpretations can shape our understanding of a play.

Anna Gát: That’s a compelling insight. In fact, the switching of couples doesn’t happen in Arcadia, but it’s fascinating to see how different directors interpret the material. The richness of the text allows for diverse readings, reinforcing its timeless relevance.

Russ Roberts: I want to share an anecdote about Stoppard. After his passing, a scientist revealed how his work had influenced their understanding of breast cancer therapies, showcasing Stoppard’s impact beyond the theater.

Stoppard’s wit shines through in works like Shakespeare in Love, which he co-wrote. There’s a story about his early ambition to be a journalist, where he humorously claimed he was interested in foreign affairs but didn’t know the current foreign minister. It speaks to his brilliant humor.

Returning to Arcadia, it’s a complex play that intertwines themes of chaos theory and the essence of knowledge. The interplay between science and art is beautifully crafted, making it a unique experience for audiences.

Russ Roberts: I once made the mistake of reading A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius in a hotel lobby, laughing uncontrollably. The contrast between its tragic themes and the humor made for an awkward situation. Similarly, Arcadia captures both humor and profound sadness, exploring our flawed attempts to understand the world.

Stoppard’s commentary on human effort, the quest for understanding, and the bittersweet nature of knowledge resonates deeply. It’s extraordinary how he crafts a narrative that reflects the complexity of human existence.

Anna Gát: Indeed, the messy nature of innovation is central to the play’s themes. One of the standout lines emphasizes that true innovation cannot occur without the groundwork laid by those before us. This idea resonates with anyone grappling with the legacy of knowledge.

Russ Roberts: I appreciate the depth of the characters representing science and art, particularly how Stoppard gives them equal weight. The play’s exploration of their respective roles offers a nuanced view of the human experience.

Anna Gát: It’s interesting to note that we never see the poet in the play, which speaks to the complexities of artistic representation. The absence of direct confrontation between these two worlds allows for a richer dialogue about their interdependence.

Russ Roberts: I want to share two quotes that encapsulate the play. The first is from Septimus, who reflects on the loss of knowledge and emphasizes the importance of moving forward. His words resonate differently as the audience contemplates the weight of lost knowledge and the inevitability of change.

Anna Gát: That’s an insightful observation. It’s crucial to recognize that the dialogue is delivered by characters, not by Stoppard himself. Each character represents a unique perspective on loss and progress, prompting the audience to reflect on their own views.

Russ Roberts: The second quote contrasts the perspectives of science and art, with Bernard arguing for the timelessness of poetry and philosophy. This debate underscores the play’s central theme of the significance of both realms in understanding our existence.

Anna Gát: Absolutely! The debate between science and the humanities has persisted for centuries, and Stoppard captures this tension beautifully. The flaws and insecurities of the characters only enhance the richness of their discourse.