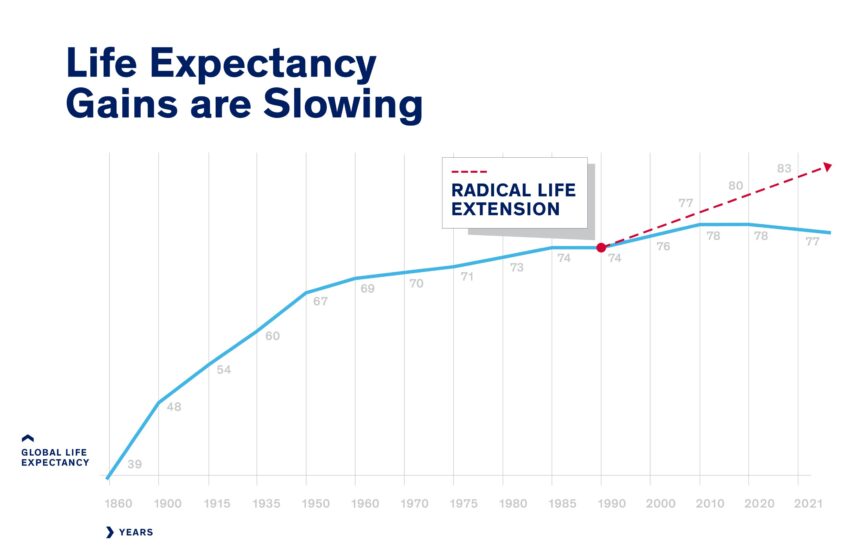

Life expectancy has been on the rise for centuries, thanks to advancements in medicine, improved diets, and overall better living conditions. However, a recent study led by the University of Illinois Chicago suggests that the rate of increase in life expectancy has slowed down significantly in the past three decades.

Despite the continuous breakthroughs in healthcare and public health, the analysis revealed that life expectancy in the world’s longest-living populations has only increased by an average of six and a half years since 1990. This slower rate of improvement falls short of the expectations that life expectancy would continue to rise rapidly in the 21st century, with predictions that most people born today would live past 100 years.

The study, published in Nature Aging under the title “Implausibility of Radical Life Extension in Humans in the 21st Century,” presents new evidence suggesting that humans may be approaching a biological limit to life. Lead author S. Jay Olshansky, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at UIC, highlights that the major gains in longevity have already been achieved through disease prevention efforts. The main challenge now lies in addressing the detrimental effects of aging.

Olshansky notes that while medicine has been able to extend life, the focus should now shift towards extending healthspan – the number of healthy years a person lives, rather than just prolonging life. The study, conducted in collaboration with researchers from the University of Hawaii, Harvard, and UCLA, challenges the belief that life expectancy will continue to increase at the same pace as in the past.

The findings suggest that efforts to combat aging and extend healthspan should be prioritized over simply extending life expectancy. While advancements in science and medicine hold promise for further improvements, the study emphasizes the importance of investing in geroscience – the study of aging biology – to unlock the potential for healthier and longer lives.

Olshansky cautions against assuming that most people will live to be 100 in this century, as the data indicates that such cases will remain outliers rather than the norm. Instead, he suggests focusing on reducing risk factors, addressing disparities in health, and promoting healthier lifestyles to enable people to live longer and healthier lives.

In conclusion, the study challenges the notion of radical life extension and emphasizes the need to prioritize efforts that slow the effects of aging and improve overall healthspan. While there may be a glass ceiling in terms of human longevity, there is still room for improvement through geroscience and other interventions that target aging processes. By focusing on extending healthy years rather than simply prolonging life, we can pave the way for a healthier and more fulfilling future.