Located over 2 billion kilometers beyond Pluto, a frigid celestial body known as Makemake has recently astounded astronomers by hosting the most distant gas ever identified within our solar system, according to new research findings.

Silvia Protopapa, a planetary scientist based at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, expressed her surprise, stating, “By surprise, we found evidence of gas” surrounding Makemake, which is currently situated 53 times farther from the sun than Earth. This discovery was detailed in a paper submitted by Protopapa and her colleagues on September 8 to arXiv.org.

With an orbital period of 306 years, Makemake is even more remote than Pluto, which takes 248 years to complete its journey around the sun. The presence of Pluto’s atmosphere was first detected in 1988 during an event when it obscured a star’s light.

Remarkably, Protopapa and her team did not anticipate finding any gaseous envelope around Makemake. Earlier observations indicated no signs of gas during its transit in front of a distant star. This was primarily because the gas is exceedingly sparse: should it form an atmosphere, its surface pressure would be roughly 100 billionths that of Earth’s atmosphere, making it approximately one-millionth the density of Pluto’s atmosphere. Nonetheless, the remarkable observations obtained from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) in 2023 were able to identify traces of this elusive gas. The JWST’s large aperture provides exceptional sensitivity, particularly in detecting infrared light, which is crucial for analyzing the compositions of these distant, icy worlds.

William McKinnon, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis who did not participate in the study, remarked on the significance of this detection, saying, “The thing that [the detection] says most of all is the extreme, fabulous power of the Webb telescope to make discoveries. It’s blown the doors off the outer solar system in terms of figuring out what’s on the surfaces of all these mysterious worlds.”

Makemake experiences extreme cold, allowing methane to freeze and form an icy surface that reflects about 80 percent of sunlight. The observed methane gas could originate from this ice vaporizing under the faint sunlight, creating an extremely tenuous atmosphere.

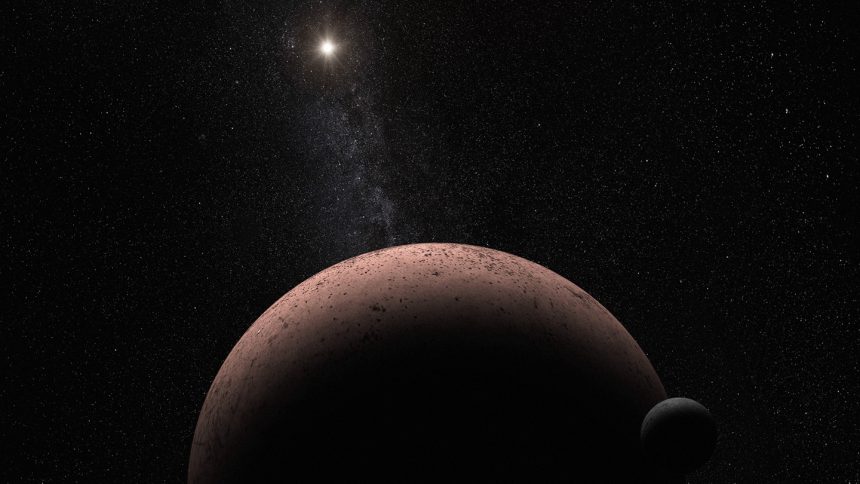

Protopapa suggests, however, an exciting alternative explanation: the potential for internal processes to produce gas plumes, akin to geysers that launch water into space from Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Although Enceladus benefits from gravitational forces that generate internal heat, Makemake could still exhibit some geological activity due to its relatively large size. With a diameter of approximately 1,430 kilometers—about 60 percent that of Pluto—it ranks as the fourth largest known object in the outer solar system beyond Neptune’s orbit.

Like Pluto, Makemake appears orange in color, likely due to the transformation of sunlight and cosmic rays altering its methane into more complex compounds. In contrast to Pluto’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere, JWST observations found no trace of nitrogen on Makemake. Researchers suspect that over time, Makemake lost its nitrogen—more volatile than methane at its frigid surface temperature—due to its weak gravitational pull. However, it remains a possibility that nitrogen ice is present beneath the methane layer.

This groundbreaking discovery raises intriguing questions: If Makemake can harbor gas, what about even more distant celestial objects in our solar system? The dwarf planet Eris, nearly twice as far from the sun as Makemake and comparable in size to Pluto, possesses both methane and nitrogen ice on its surface. However, a 2010 observation while Eris was in transit before a star did not reveal any gas. To date, JWST observations have yet to detect gas around Eris. Currently, Protopapa notes, Makemake is unique in its display of methane emissions at such a significant distance from the sun—but future observations from JWST could potentially illuminate new findings about Eris and other remote worlds.