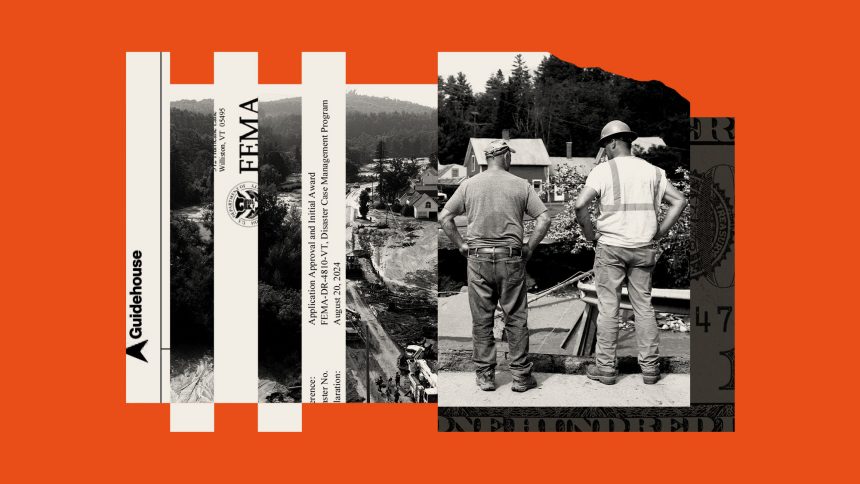

This article is part of The Disaster Economy, a Grist series focusing on the often tumultuous yet profitable realm of disaster response and recovery. Supported by the CO2 Foundation.

On August 21, Jason Gosselin sounded the alarm: the budget for the flood recovery initiative he oversaw was depleting more rapidly than expected. An email to colleagues ended with an anxious note: “(calm down, Jason, calm down…).”

In July 2024, Vermont faced the rare occurrence of 100-year flooding for the second consecutive summer. Among the federal assistance approved by FEMA was a substantial $2.9 million grant intended to employ an 11-member disaster case management team to assist victims with FEMA applications, locate additional resources, and facilitate home reconstruction. Originally meant to last two years, funds were set to run out much sooner. The day following his first email, Gosselin, the emergency management director at the Vermont Agency of Human Services, revealed another troubling revelation: the corporate contractor managing the team was charging nearly half of the budget for its personnel.

“We cannot/will not be able to support this,” Gosselin concluded. Documents obtained by Grist indicated that his worries were justified, and the situation was even more dire than he realised.

State records revealed that approximately $400,000 was retained for employing state administrative staff. The remaining $2.5 million was for Guidehouse, a global consulting firm, to recruit the frontline workers. However, Guidehouse ended up subcontracting only seven workers instead of the promised eleven, costing $1.1 million. This decision left over a million dollars available for the company to allocate toward its own operations.

“There is a massive demand in the state,” stated Prem Linskey, a case management supervisor at the Vermont aid organization Recovery After Floods Team. The workload is often overwhelming with numerous individuals requiring assistance. “The state’s plan for case management could have been significantly more effective if they had employed more personnel.”

A Vermont official told Grist that initial costs exceeded expectations, but the state has since taken measures to cut down expenses. Despite the relatively modest size of Vermont’s grant compared to the billions FEMA distributes annually, experts caution that poor oversight, unclear contract specifications, and exorbitant consulting fees are unfortunately prevalent. Such gaps are predicted to expand as climate change exacerbates severe weather conditions, especially with continued federal pressure on states ill-equipped for these challenges. If a federal grant is mishandled, it is often the state that bears the financial repercussions, with potentially significant consequences.

At the end of last month, FEMA warned Gosselin and his team in a firm yet informal email regarding the potential repercussions if they didn’t rectify the situation. “Deficiencies might lead to various consequences, including corrective action plans and formal audit findings, which could hinder a state’s eligibility for federal funding across the board, not just from FEMA,” stated Penelope Doherty from the agency’s regional office.

The flooding last year resulted from two distinct severe storms. On July 10, parts of Vermont saw rainfall of up to 7 inches within just hours. Following that, on July 30, with already saturated soil and swollen rivers, the Northeast Kingdom region experienced an additional 8.4 inches. The torrential downpours claimed two lives, obliterated homes, and resulted in billions in damages. Within weeks, FEMA granted an official disaster declaration, and Vermont mobilized a temporary “bridge” team of case managers, primarily sourced from other state roles, to assist with the urgent needs. As that program was nearing closure by year’s end, and with many cases still unresolved, the state submitted a grant application to FEMA shortly before Christmas to address the “unmet needs” of affected Vermonters.

In the application, Vermont projected that 134 flood survivors still required disaster case management services, or additional help in developing recovery strategies. The $2.5 million portion of the grant was to fund seven disaster case managers, three construction managers, and a supervisor. No other roles were specified within the application or budget submitted by the state.

In February, FEMA accepted Vermont’s $2.9 million “Disaster Case Management Program.” Subsequently, the state contracted Guidehouse, a firm that evolved from the public sector branch of PwC, which now operates as a $7 billion entity owned by Bain Capital.

Since 2020, Vermont has collaborated with Guidehouse, particularly during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The state issued a competitive bid and entered into a five-year master contract with Guidehouse, allowing its agencies to request services from the firm without further bidding. While much of the initial work was related to the COVID crisis, the governor mentioned in 2024 that the company was also assisting with the state’s flood response.

This past April, Vermont’s secretary of human services, chief recovery officer, and an assistant attorney general approved a $2,483,000 task order with Guidehouse for the FEMA disaster management grant. Gosselin was identified as the primary contact, with wording such as “The Contractor shall support the State in administering its DCM Program” and “Provide implementation and strategic advisory assistance to the State” included in the agreement. Specific staffing requirements were notably absent.

Upon approval, Guidehouse began subcontracting for the necessary frontline personnel. They turned to the New England Annual Conference of the United Methodist Church (NEAC), previously involved in Vermont’s flood recovery initiatives. Yet, this subcontract deviated significantly from the terms outlined in the FEMA agreement; NEAC was tasked with providing just four case managers and two construction coordinators, instead of the originally planned seven and three. They were offered just $1,098,875.00 for these services, a figure below half of what Guidehouse received from the state and FEMA. The specific intended use of the remaining $1.4 million by Guidehouse remains unclear, but agreements indicated the company employed six individuals for the project, leading to a near one-to-one ratio with frontline staff.

All federal grants incur a degree of administrative expenses, explained MaryAnn Tierney, a former FEMA regional administrator. However, when funds earmarked for services are diverted to overhead, “that’s unacceptable,” she asserted.

Another former FEMA official, preferring anonymity due to ongoing consulting work with the federal government, suggested that agency frustration typically arises when such expenses surpass 20 percent of the budget. “While it doesn’t necessarily imply fraud, it typically raises concerns regarding inefficient spending,” the official noted.

According to Craig Fugate, who served as FEMA administrator from 2009-2017, Vermont’s situation exemplifies the pitfalls of vague contracts. He insisted that any agreement should outline specific deliverables and impose penalties for non-compliance.

In the absence of robust contracts, consultants can effectively dictate their own limits, leading to excessive expenditures focused on process rather than results. “You notice considerable funds allocated toward meetings and reviews, although the actual productivity remains low — resulting in an abundance of billable hours,” Fugate remarked.

By the time Gosselin undertook his accounting in August, Guidehouse had already billed nearly 4,877 hours, equating to just over half a million dollars. His calculations showed that 48 percent of the funds were directed towards Guidehouse employees. Additionally, the consulting firm marked up the hourly rates of NEAC staff, resulting in an even larger portion being allocated to the company.

Sources involved with the grant indicated that it was not unusual for multiple Guidehouse staff to attend the same meetings, often leaving participants perplexed as to their necessity. “It created a certain level of confusion,” one participant noted. Concerns were also raised regarding the role played by Lina Hashem, a Guidehouse director, particularly given her billing rate of $293 per hour.

Prior to his leadership at FEMA, Fugate amassed significant experience as an emergency manager at both state and local tiers. He noted that the reliance on contractors has grown substantially; whereas firms once predominantly supplied goods, they now focus more on offering service-based solutions, such as consulting.

While outside companies can significantly bolster disaster response capabilities by providing specialized expertise, Fugate underscored that responsibility for recovery should not be entirely passed onto contractors. “During events like Hurricane Katrina, states will struggle to have adequate manpower in place,” he explained, yet maintaining oversight remains critical.

FEMA allocates tens of billions of dollars annually toward disaster recovery, augmented by additional federal funding across various departments: over two dozen other agencies run approximately 100 distinct response and recovery programs.

Numerous instances of contractor misconduct or state mismanagement have surfaced throughout the years. For instance, following a 2014 tornado in Mississippi, FEMA’s inspector general advised the agency to recoup $25 million due to improper procurement by the city. Recently, a consulting firm named Horne paid a penalty of $1.2 million for questionable billing relating to the aftermath of intense rainfall in West Virginia in 2016. Horne now holds a contentious $81 million contract in North Carolina for Hurricane Helene recovery efforts.

Guidehouse’s operations have also faced increased scrutiny. Last year, it agreed to pay a $7.6 million fine due to a data breach connected to its role in administering New York’s rental assistance program amid the pandemic. Nevertheless, it has established itself as a key player in disaster management across the nation, winning contracts such as the $135 million contract to revamp the National Flood Insurance Program and a $38 million agreement for identity verification services with FEMA. Additionally, the company has acquired portions of a firm that collaborated with New Jersey post-Sandy and Florida following Hurricane Irma.

As per Vermont’s vendor payment portal, Guidehouse has received $41 million since 2020, but not all interactions have been unfavorable. Ben Rose, who recently retired as Vermont Emergency Management’s recovery and mitigation section head, noted that Guidehouse was vital in supporting the state through both the pandemic and 2023 flooding. “Hiring through the state system can be challenging,” he stated. “Utilizing consultants allows for greater responsiveness.”

Nonetheless, Rose recognized Guidehouse’s profit-driven nature, stressing the necessity of monitoring its work and spending. “Sometimes they would propose, ‘Let us draft the task order to simplify things for you,’” he recalled, with Rose subsequently removing unnecessary elements. “It was a constructive process.”

In his August correspondence, Gosselin appeared taken aback by the extent of the grant funding allocated to Guidehouse. After FEMA began probing for clarification, the state was slow in detailing its expenditures. In one of her communications, Dougherty pointed out that the state had “indicated a decision to reduce service delivery staff,” which would have been acceptable if accompanied by a corresponding budget cut. Yet, over two months later, and after several draft proposals, she remarked that a formal update to the original plan was still pending.

“We have been requesting this clarification since mid-July,” Dougherty noted in a late September message. “[It] needs to be finalised to avert any corrective actions.”

The state is presently collaborating with FEMA on an updated strategy, according to Douglas Farnham, Vermont’s Chief Recovery Officer. He defended the partnership with Guidehouse, asserting that it was a fitting choice for the project, given their existing relationship and the urgency for swift program implementation. “While they may not be the least expensive option, their expertise is considerable,” Farnham noted, while acknowledging that expeditious action incurs added costs. He attributed the high initial billing, where nearly half went to Guidehouse, to start-up demands for the project.

“Ideally, we wouldn’t see costs soar that high,” he mused, but after reviewing expenses, the state concluded that they were reasonable. “Our belief is that these expenses are justified; they were essential for program establishment, and we’ll reconcile with FEMA.”

FEMA’s response was unavailable, likely due to the ongoing government shutdown.

Farnham stated that Vermont has established a new target for Guidehouse’s billing to 17 percent of overall costs, with the remaining funds allocated for program delivery. “This certainly helps stem the major losses,” suggested an informed source, while still questioning the necessity of Guidehouse’s ongoing involvement. Due to these alterations being implemented months into the project and over a year post-disaster, some insiders argue that considerable damage has already been inflicted.

Vermont has already remitted hundreds of thousands to Guidehouse, pending reimbursement from FEMA. Farnham expressed concern that should FEMA decline compensation, the state would have to rely on its reserve fund. Complicating matters further was the timing of the FEMA-funded case management initiative, which did not receive approval until seven months after the disaster declaration. While grateful for the funding, Farnham attributed delays to FEMA’s “extensive and complex” application processes.

Furthermore, the state employed a lower headcount than anticipated because the volume of cases was not as high as expected, indicating that the flexibility of a contractor allows for adaptable staffing. However, Guidehouse’s October 1 report indicated a “medium” risk of caseloads exceeding the project team’s budgeted capacity.

Farnham remains optimistic this will not become an issue, expressing a preference to extend the project duration to cover future arising cases. Although FEMA has not yet agreed to this extension, Dougherty advised the state in a September email to “be cautious of the inherent contradiction in asserting urgency while claiming outreach results justify workforce reduction.”

Guidehouse’s contract with Vermont is limited to disasters occurring up to June 2025, and the state has selected a different company for its upcoming master contract. Farnham did not elaborate on this decision, nor did Guidehouse comment on this report, nor did NEAC. Gosselin did not respond to several requests for interviews or written inquiries. Long-term recovery organizations assert that even once the state finally engaged in case management, coordination with existing ground entities was poor. “They perplexed everyone,” noted Meghan Wayland, president of the Kingdom United Resilience & Recovery Effort. “They contacted individuals in our neighborhood, which led to chaos that we then had to address.”

Wayland and Linskey emphasized that improved collaboration with organizations like theirs could have maximized the efficacy of FEMA-funded workers. For instance, the NEAC could have taken on particularly challenging cases or concentrated efforts in regions lacking adequate local resources. “They could have structured a program that would substantially benefit Vermonters without undermining ongoing efforts,” remarked Wayland. “Such an approach would have been incredibly beneficial.”

Several individuals have identified Gosselin as a significant contributor to the state’s challenges. “He lacks the requisite skill set for the role he’s been given,” stated Wayland. Another individual remarked, “We continually strive to rectify [his] mistakes, but the issues are extensive.” Nevertheless, it’s important to note that Gosselin was not a signatory on the Guidehouse task order or the FEMA application, both of which were reportedly reviewed by higher-ranking officials, including Farnham. Gosselin was commended by Farnham for highlighting Guidehouse’s billing for further evaluation and asserted that “in all matters concerning this, I believe he has acted appropriately.”

Currently, FEMA’s review of Vermont’s expenditures is still ongoing. Yet the emerging insight appears evident: As flooding incidents proliferate and funding increases, the effectiveness of America’s recovery system hinges solidly on the durability of its contracts. At present, states might indeed be the frail link in that chain.

“By transferring responsibilities from the federal level to state authorities, it inadvertently establishes a marketplace for private contractors,” remarked a FEMA employee who requested anonymity, as they were not authorized to speak publicly. “They are effectively left vulnerable.”