The bustling opening night of the International Center of Photography’s (ICP) annual Photobook Fest was vibrant, reflecting the current political climate as it unfolds in Lower Manhattan through Sunday, October 5. Within a maze of books from 70 distinct publishers, many focused on photography and image-centric literature, it was those booths that boldly integrated art with pivotal political discourse that drew the most attention from attendees.

This event, occupying two spacious floors, had an audible flow of Spanish, more so than at any other art fair I’ve experienced this season.

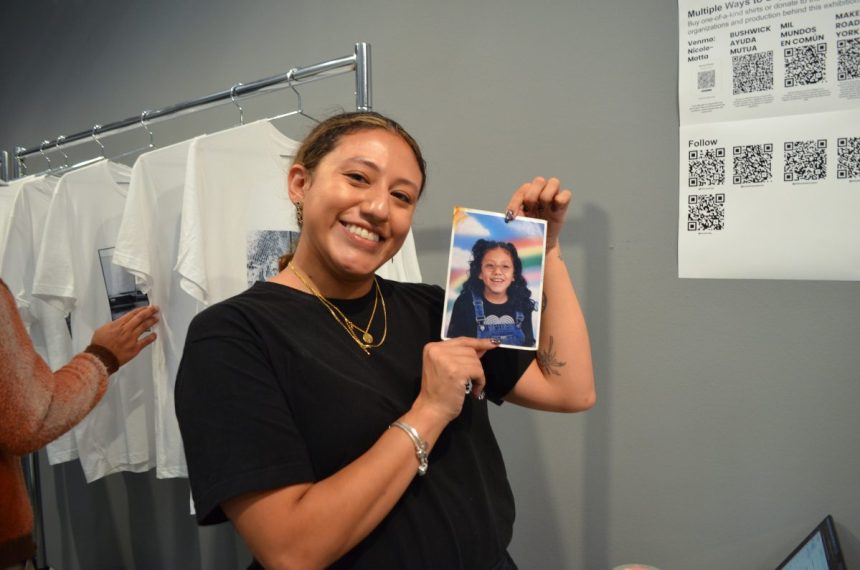

On the second floor, I encountered Nicole Motta, a Peruvian-American artist based in Queens, capturing the interest of numerous attendees as they browsed through an array of community-centered family photographs. Organizing her exhibit, Sin Poder No Hay Paraíso (translated to Without Power There is No Paradise), in merely a week, Motta created a compelling showcase.

Motta assembled a collection of images showcasing 12 artists from New York City, emphasizing themes of love and resilience, and printed them onto white T-shirts for attendees to explore as we conversed. She views this exhibition as a means to regain power through images during challenging times under the Trump administration. The T-shirts, priced at $120, support mutual aid and immigration efforts, as per Motta’s commentary.

“We aim to bring light to immigration and working families,” Motta expressed. “Seeing all the disturbing images on social media made me recognize our lack of community.”

She observed that participants engaged with her tactile exhibition without their phones. “It’s beautiful to see people connecting in person and realizing the humanity behind the art we create while actively engaging in conversations,” reflected Motta.

Meanwhile, downstairs, photographer Martha Naranjo Sandoval showcased her work under the banner “No human is illegal.” This exhibit featured an eclectic mix of images, from birds in Cuba to a series on queer motherhood, alongside a matchbox-sized book capturing her film contact sheets. Naranjo Sandoval, who runs a press called Matarile Ediciones dedicated to immigrant photographers, noted, “People often overlook the humanity of immigrants,” relating the significance of the banner’s message, echoed in packaging from her press.

Upstairs, Egyptian-American photographer Anthony Hamboussi presented his work through his press, L Nour Editions, named in honor of his daughter. In 2019, he orchestrated a significant exhibition titled Our Land, a response to the Brooklyn Museum’s controversial exhibition This Place, criticized for how it portrayed the Israeli occupation of Palestine. At the fair, he featured his photography books, including one dedicated to New York City’s industrial waterways.

Hamboussi, whose roots trace back to Palestine through his grandfather, also showcased a book titled “Through Pictures and Posters 1967–1986” (2025), compiling a selection of posters from Palestinian resistance movements. Recently, he noted, many approached him expressing sympathy regarding the Israeli atrocities in Gaza, but he stressed the importance of his poster collection in shedding light on the long-standing Israeli occupation.

Nearby, photographer Elijah Gowin managed his table for Tin Roof Press, a platform he founded in 1998. He believes that photo presses democratize photography, making it accessible as opposed to gallery-priced artworks. This year, his press printed works by Japanese-American photographer Osamu James Nakagawa, who endeavored in 2022 to document every Japanese incarceration camp from 1942. Printing Nakagawa’s work in tabloid format, they sold for $20 each.

Gowin remarked, “This project addresses current events and news. Noticing the discussions about American identity in the media, I realized this was the perfect opportunity to present this work in a tabloid format.”