When the Civil War ignited in 1861, the Confederacy, like any entity facing a financial crisis, had three main avenues for funding its efforts: taxation, borrowing, and printing currency.

Taxation

The Confederacy faced a perpetual uphill battle in attempts to extract taxes from its populace. Historian James M. McPherson notes that “Congress enacted a modest tariff in 1861,” which yielded a mere $3.5 million for the entire duration of the war, hampered in part by the federal blockade. As he elaborates:

…a direct tax of 0.5% on real and personal property was legislated. The Richmond government depended on the states for collection. Only South Carolina complied; Texas resorted to seizing northern-owned properties to fulfill its obligations, while other states opted to meet their assessments through borrowing or printing their own money!

In April 1863, the Confederacy introduced more extensive fiscal strategies, including a progressive income tax, an 8% levy on specific goods, excise and license fees, and a 10% profits tax on wholesalers aimed at punishing “speculators.” Yet, as it turned out, the Confederacy needed tangible resources, not depreciating currency, prompting the imposition of a 10% “tax in kind” on agricultural outputs—a move that alienated many potential supporters. While people were willing to fight for the Confederacy, few were inclined to finance it.

Borrowing

The Confederacy’s borrowing capacity was closely linked to its military prospects. “The initial bond issue of $15 million was quickly taken up,” McPherson explains:

Further Congressional actions in May and August of 1861 sanctioned the issuance of $100 million in bonds at an 8% interest rate. However, these bonds sold sluggishly. Even the most patriotic southerners hesitated to invest in bonds at an 8% return when inflation had already escalated to a staggering 12% monthly by late 1861.

Moreover, both tax collection and borrowing attempted to siphon cash from a society that was, quite frankly, cash-strapped. Much of the Confederacy’s wealth was tied up in land and enslaved individuals, which are not exactly liquid assets. “Although the Confederate states possessed 30% of the national wealth (in the form of real and personal property),” McPherson highlights, “they held only 12% of the circulating currency and 21% of the banking assets.”

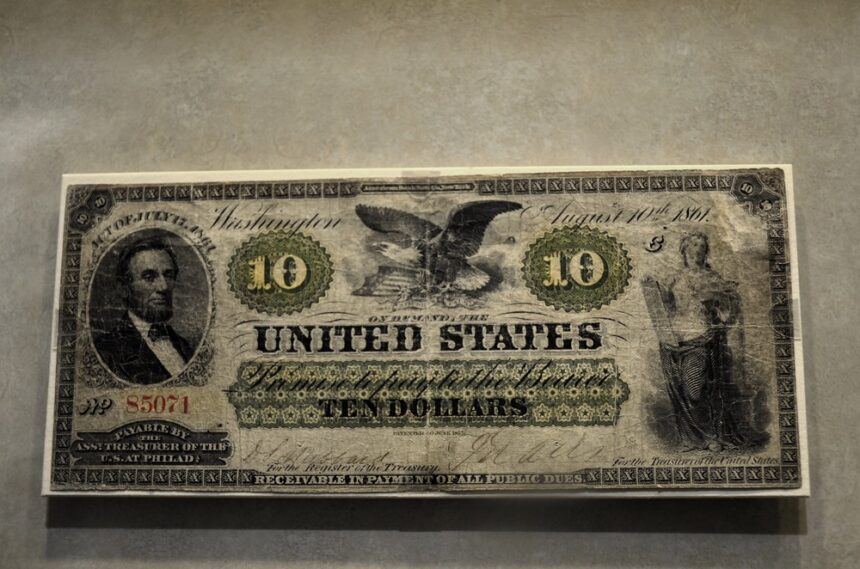

Printing Money

Faced with these constraints, Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger voiced concerns that printing currency could be “the most perilous method of raising funds.” Nevertheless, the Confederacy found itself with few alternatives. Congress approved the issuance of $20 million in treasury notes in May 1861, followed by $100 million in August, $50 million in December, and another $50 million in April 1862. “During its first year,” McPherson states:

…the Confederate government derived three-quarters of its revenue from the printing press, nearly a quarter from bonds (often bought with those same treasury notes), and less than 2% from taxes. Although the proportions of loans and taxes increased slightly in the subsequent years, the Confederacy primarily financed itself with an astounding one and a half billion paper dollars…

Memminger cautioned that “The excessive volume of money in circulation today will inevitably lead to depreciation and financial catastrophe,” and he was not wrong. Initially, currency depreciation was gradual, buoyed by Confederate victories in the summer of 1861. However, as McPherson notes, economist Eugene M. Lerner recorded that by June 1862, the real value of the money supply was 2% higher than in January 1861, due to the money supply growing faster than commodity prices. But as time progressed, prices surged more rapidly than the money supply, leading to a decline in its real value: by January 1864, it had plummeted to 58% less than levels in January 1861, and by the start of 1865, it was approximately 80% below that value.

As military defeats dimmed the Confederacy’s hopes, confidence in the ability to redeem Confederate notes at face value diminished, leading holders to offload them rapidly. “She requested 20 dollars for five dozen eggs and then said she would accept it in ‘Confederate,’” noted diarist Mary Chestnut in 1864: “When they ask for Confederate money, I never hesitate. I readily hand over 20 or 50 dollars for anything.”

In terms of the equation of exchange, the demand for Confederate currency plummeted, and its velocity (V) soared, exacerbating the inflationary pressures stemming from increased money supply (M) and diminished production (y) as war ravaged the South. Notably, economist Milton Friedman famously claimed:

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

This perspective, however, overlooks the significance of the demand for money. Elsewhere, Friedman summarized inflation (P) as too much money (M) chasing (V) too few goods (y), which encapsulates the narrative of Confederate hyperinflation more accurately.

Readers may also be interested in this poetry collection on the Civil War.

John Phelan is an Economist at Center of the American Experiment.