You’re getting pushback from the health economists. Let’s drop it.” And we did.

But here’s where I think Marty sold Reagan short. Marty thought that Reagan would not go along with our proposal because, he thought, Reagan was a free-market ideologue. To Marty’s surprise, Reagan did go along with it. I’m not sure what Marty’s reaction was because after the decision was made, I was transferred to the Department of Commerce and lost touch with him. But I do know that Reagan was not the ideologue that Marty thought he was. Reagan was a pragmatist. He had certain principles, to be sure, but he also had a penchant for doing what worked. In this case, doing what worked meant going along with our proposal to make employer contributions to employees’ health insurance above a certain amount taxable income. I think Marty’s mistake was in not recognizing Reagan’s pragmatism.

So, what does this have to do with Reagan’s intelligence and knowledge? One thing I didn’t mention above is that Reagan’s intelligence extended to a knowledge of the political process. He knew that in a country as diverse as the United States, he couldn’t get everything he wanted. So he was willing to compromise. That’s a sign of political intelligence. And in our case, it was also a sign of economic intelligence because he could see that our proposal made sense. So Reagan’s intelligence and knowledge were not just economic. They were also political. And they were also pragmatic. All of which are features of a great leader.

I really should write a longer piece on Reagan someday. I’ve been meaning to do that for years.

In the world of politics, power dynamics and decision-making processes can be quite complex. This was the case in a particular instance involving Marty and Reagan, as recounted by an individual who was privy to the details. Marty, a key figure in the story, had devised a proposal that he presented at a Cabinet Council meeting. However, what stood out was the fact that the narrator, who would typically have been present at such meetings as a silent observer, was left out this time. It was only through a colleague from another department that the narrator learned about the meeting post facto.

It seemed that Marty had a keen understanding of the narrator’s personality – someone who was not afraid to voice their opinions if they disagreed with something. This insight into the narrator’s character likely led Marty to exclude them from the meeting, fearing that their outspoken nature could disrupt the proceedings. Had the narrator been informed beforehand about their exclusion, they humorously remarked that they would have agreed to anything, even if it was as outlandish as claiming the earth is flat.

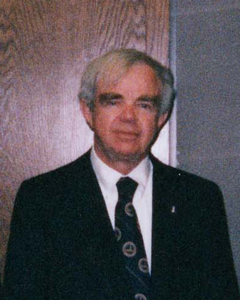

Despite not being present at the meeting, the narrator was curious to know how things had transpired. When they approached Marty for feedback, his response was somewhat dismissive, stating that “Even the President understood.” However, the narrator, having followed Reagan’s thought process for several years, believed that Marty had underestimated Reagan’s intelligence and grasp of the situation.

In the intricate web of politics, it is fascinating to observe how individuals navigate relationships, power dynamics, and decision-making processes. The tale of Marty, Reagan, and the narrator provides a glimpse into the inner workings of a high-stakes political environment. It serves as a reminder that perceptions and assumptions can often shape the way individuals interact and make decisions, ultimately influencing the outcomes of important meetings and discussions.