A groundbreaking study conducted by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health has identified a new biomarker that can be used to measure the accumulation of uranium in the kidneys. This discovery could serve as an early warning sign of kidney damage caused by uranium exposure from drinking water.

Published in the prestigious journal Environmental Science & Technology, the study highlights the potential breakthrough in detecting and preventing chronic kidney disease resulting from uranium toxicity. The newly identified biomarker, based on uranium’s isotopic composition in urine, offers valuable insights into an often overlooked environmental health hazard.

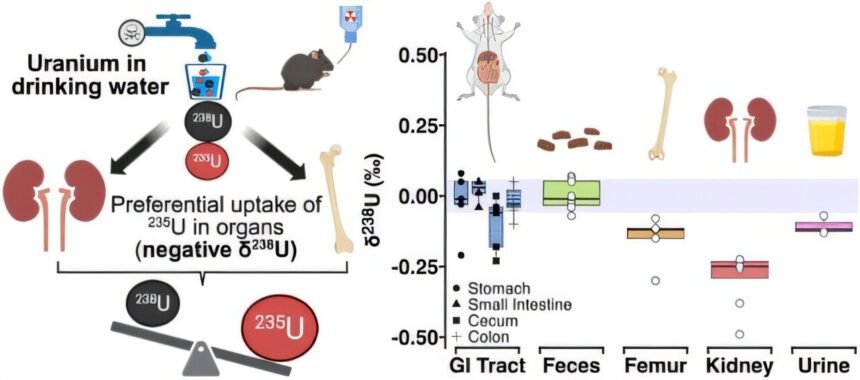

Lead author Anirban Basu, Ph.D., a geochemist and research scientist at Columbia Mailman School, explained, “Uranium present in drinking water is filtered by the kidneys, where it can accumulate and pose a risk of harm over time. Our research indicates that measuring uranium isotopes in urine can provide a noninvasive method for detecting kidney accumulation and assessing the risk of damage.”

The study revealed that nearly two-thirds of U.S. community water systems, serving around 320 million people, have detectable levels of uranium. Approximately 2% of these systems exceed the EPA’s maximum contaminant level of 30 micrograms per liter (μg/L). Furthermore, about 4% of private wells, which cater to 15% of the population, surpass the MCL.

Although uranium is commonly known as a radioactive element, its chemical toxicity, especially to the kidneys, is the primary concern at environmental exposure levels. Even low concentrations of uranium below the MCL can impair kidney function, posing a significant health risk.

The research found that uranium accumulation in the kidneys, particularly in the outer layer where it binds to cells and causes damage, can lead to chronic kidney disease over time. Current methods for measuring uranium levels in the body do not provide specific information on kidney accumulation, hindering efforts to understand and prevent long-term kidney damage from uranium exposure.

In experiments with mice, the researchers observed distinct isotopic signatures of uranium accumulation in the kidneys and bones after exposure to contaminated water for just 7 to 14 days. This groundbreaking finding demonstrates that the isotopic composition of uranium in urine can serve as a valuable biomarker for monitoring kidney uranium levels, especially in communities at higher risk of exposure.

The study represents a crucial step towards enhancing environmental health surveillance and developing tools for monitoring metal exposures in vulnerable populations. Future research will focus on longer exposure periods and lower uranium doses to gain a deeper understanding of the long-term effects of uranium toxicity on kidney health.

The study’s co-authors include experts from Columbia Mailman School of Public Health and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia Climate School, underscoring the interdisciplinary approach taken to address this pressing public health issue.

This innovative research underscores the urgent need for improved detection methods and interventions to mitigate the harmful effects of uranium exposure on kidney health. By leveraging uranium isotopes as a biomarker, healthcare professionals can enhance monitoring efforts and potentially prevent irreversible kidney damage in at-risk populations.

(Source: Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health)