Coal has seen a steady decline in New England, with coal generation falling by over 90% in the decade leading up to 2017. The closure of New England’s largest coal facility that year left only a few remnants of coal power, which subsequently shut down one after another.

Now, the final coal plant in New England—Merrimack Station—has officially closed its doors. Let’s explore the reasons behind this shift and consider the future landscape of energy in the region.

The Rise and Fall of Coal

The Merrimack Station power plant in Bow, New Hampshire, began operations in 1960 with its first generator, followed by a second in 1968. After six decades of service, it had become quite aged, even by the standards of an aging U.S. coal fleet.

However, it wasn’t merely its age that led to its decline; it was primarily economic factors.

A regional grid operator tends to call upon the least expensive power plants first to meet electricity demand. As regional demand grows, pricier sources are tapped into. The economic viability of coal generation has plummeted in recent years, challenged not only by the rise of natural gas but also by the emergence of increasingly affordable solar and wind energy, along with energy storage options. Consequently, the high operational costs of coal plants have resulted in a significant reduction in their utilization.

Merrimack Station’s decline mirrored the nationwide trend of diminishing coal usage, as the plant saw minimal operation in recent years. Although theoretically capable of operating nearly year-round, maintaining a high capacity factor—the ratio of actual electricity output to potential output—the Merrimack’s capacity factor, which stood at 70-80% two decades ago, fell below 8% in the last six years. In 2024, one of its generating units operated for just 25.4 hours, and the plant overall contributed to less than 0.25% of New England’s electricity generation.

The situation worsened for the plant’s owners in 2023 when, for the first time, Merrimack Station failed to secure a contract in the regional capacity auction. The capacity market compensates power plants to remain ready to generate energy, even if they aren’t utilized. Merrimack Station could not compete with cheaper alternatives such as fossil fuels, nuclear, renewable energy, and energy consumers who can reduce their electricity usage during peak demand periods.

Additionally, while fossil fuel plants like Merrimack Station produce electricity, they also generate emissions that impact the surrounding community. Despite installing pollution control measures over the years, the plant continued to contribute significantly to local pollution levels. Its carbon emissions only decreased as its generation fell; at peak capacity years ago, it emitted the equivalent of approximately 800,000 of today’s average gasoline cars. While its electricity output may have been valued, the accompanying pollution remained an unwelcome legacy.

What Comes Next?

In recent years, Merrimack Station primarily operated during colder months. Analysis shows that winter accounted for eight of the ten months with the highest demand on the plant in the last five years. Even during particularly frigid winters, its capacity factor exceeded 30% only twice in its last three years of operation.

However, New England is increasingly turning to a cleaner and more efficient answer for winter electricity demands—offshore wind energy. Winter storms often come with significant winds, boosting electricity demand while simultaneously offering ample kinetic energy for offshore wind turbines to convert into electricity.

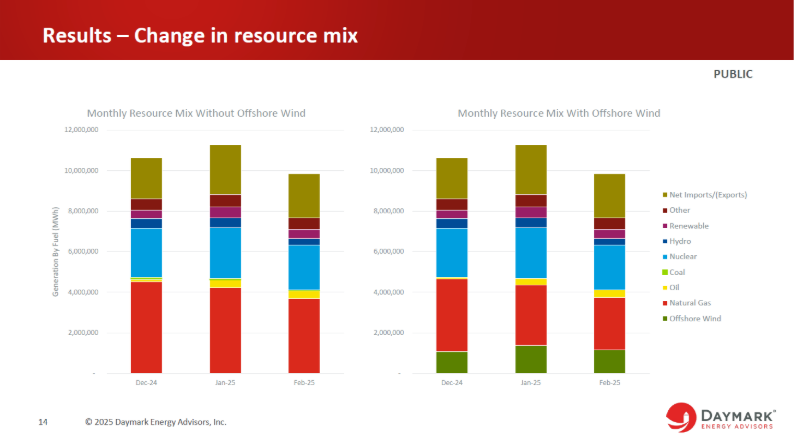

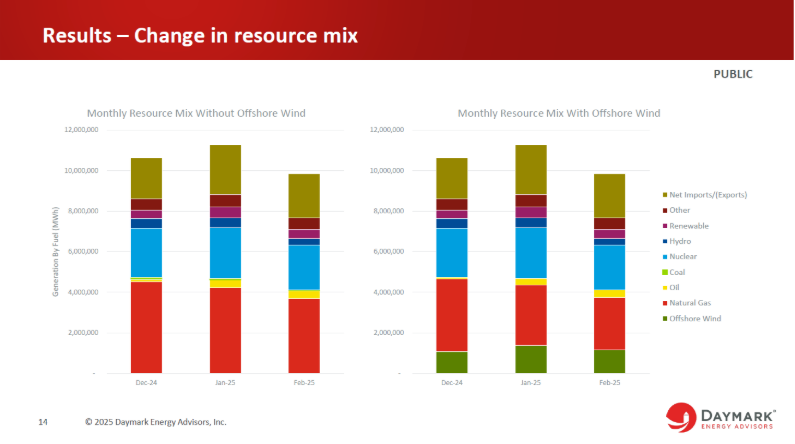

This strong relationship between peak demand and the potential for substantial wind energy generation can be observed in the graph below from a recent study regarding the economic advantages of offshore wind in the region, indicating that wind facilities will not only take the place of the scant coal energy from Merrimack but also reduce reliance on expensive and highly polluting oil peaking plants and gas plants. The offshore wind potential is depicted in green, replacing the minor coal contribution (represented by a thin light green strip) and decreasing shares from oil (yellow) and gas (red).

Source: Daymark Energy Advisors 2025

During periods of extreme winter weather, the grid operator tends to rely on the more expensive generators, driving up electricity costs. By displacing these less efficient sources, offshore wind farms can reduce consumer electricity bills despite their higher construction costs.

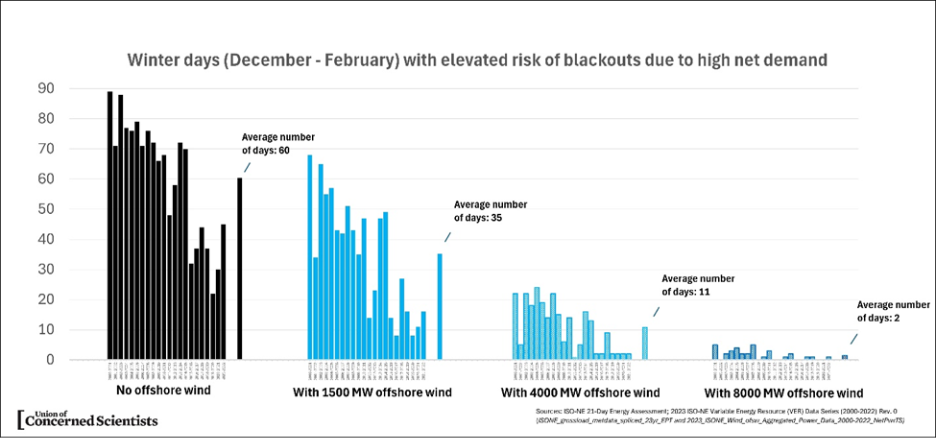

Furthermore, these winter peaks also pose a high risk of power outages, as gas plants—responsible for supplying half the region’s electricity—face competition for gas supplies from homes and businesses using gas for heating, and backup oil plants can run low on fuel. Thus, a solid base of offshore wind capacity could dramatically mitigate the demand-driven risks of winter blackouts (see below).

Source: UCS 2024

At the same time, the growing number of solar installations in New England is effectively addressing summer peak demand that Merrimack Station may have once been called upon to manage.

A Clearer Future Ahead

New England has officially moved on from coal plants.

Aside from a paper mill in Maine that intermittently utilizes coal for its energy needs, the remaining connection to coal in the region is solely through interconnections with neighboring areas still operating some coal power, along with the connections among various regional electricity grids. While coal may not be part of the local energy supply, the effects of coal pollution can still permeate into New England.

This retirement marks a significant milestone, representing how infrequently New England’s last coal plant was utilized before its closure. It highlights the remarkable evolution of electricity generation both regionally and nationally. The ability to seamlessly substitute its output with cleaner and more affordable energy sources showcases the advances made in renewable energy technologies and energy storage solutions.

Some of this replacement may occur right at the now-defunct coal plant’s location, potentially restoring jobs and tax revenue that were lost when it closed: the owners of Merrimack Station’s site are exploring possibilities for installing solar and storage systems there.

The transformation of New England’s energy landscape is just beginning.