New York City’s reputation as a hub for medical specialists may not be as advantageous as previously thought, according to a new study published in Nature Cities. The research, led by Maurizio Porfiri, an NYU Tandon Institute Professor, challenges the assumption that larger cities provide better access to specialized healthcare services.

The study analyzed data from 1.4 million healthcare providers across 75 medical specialties in 898 metropolitan and micropolitan areas. By examining each specialty individually, the researchers found that 88% exhibited “sublinear scaling,” meaning that larger cities actually have proportionally fewer specialists per resident than smaller cities.

Porfiri’s urban scaling methodology, which has been used in previous studies on gun violence patterns and city living, ADHD, and obesity, revealed that while cities like New York and Chicago offer nearly all medical specialties, residents may face longer wait times and specialists may have higher patient loads.

Smaller cities, on the other hand, may lack certain specialties altogether, but the ones they do have serve fewer patients per provider. For example, Marshfield, Wisconsin provides 16.8 specialists per 1,000 residents compared to New York’s 4.7 per 1,000.

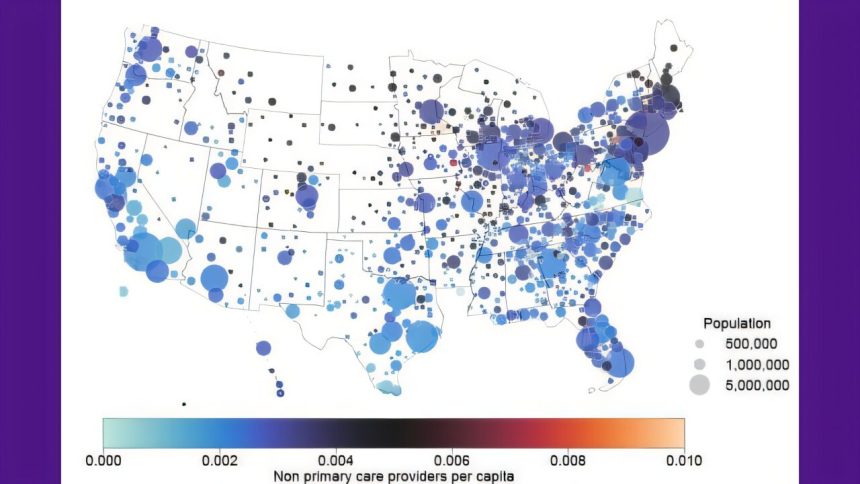

The study also identified geographic disparities in specialist concentrations, with the Midwest having the highest concentrations and the South having the lowest access. Certain specialties, such as addiction medicine, preventive medicine, osteopathic manipulative medicine, and micrographic dermatologic surgery, were found to be particularly underrepresented in large cities.

The research highlights the need for policymakers to consider the complex interplay between diversity and provision of medical services in urban areas. Moving beyond the traditional urban-rural dichotomy, the study provides a framework for understanding healthcare distribution and addressing geographic inequalities in access to specialized care.

The findings have important implications as the U.S. population ages, with major metropolitan areas potentially being unprepared for the growing elderly population. By shedding light on the paradoxical nature of healthcare access in large cities, the study calls for a reevaluation of assumptions about urban health advantages and the need for more targeted and equitable healthcare provision across different population centers.