There’s a crucial lesson that libertarians might glean—or should be learning—from the current American administration regarding the rule of law. A striking example emerged on March 13, when Ursula von der Leyen unveiled the European Union’s countermeasures against Trump’s hefty 25% tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. (For a deeper dive, refer to “EU and Canada Retaliate after Donald Trump’s Metals Tariffs Take Effect,” Financial Times, March 12, 2025, which includes a brief video of von der Leyen’s announcement.) As the president of the European Commission, she calmly articulated that the EU’s retaliatory tariffs were proportional to those imposed by Trump, highlighting that the trade war initiated by him was detrimental both to businesses and consumers alike. While unilateral free trade would have been the ideal solution for consumers, this measured response starkly contrasts with the erratic, one-man show that characterized the American announcement. However, this is just one illustration of a much larger narrative.

In my view, the rule of law represents the ideal championed by the classical liberal tradition, particularly by thinkers like Friedrich Hayek. It consists of “rules governing the interactions among individuals, applicable to an unpredictable number of future scenarios, and defining the boundaries of the protected realm for all individuals and organized groups,” including government agents themselves (refer to Hayek’s Law, Legislation, and Liberty, p. 457 and throughout). This embodies the principle of governance by laws rather than by individuals.

We are, once again, recognizing that the rule of law is indispensable for safeguarding individual liberty and, consequently, prosperity—at least until we achieve what some might call a liberal or capitalist anarchy, if such a moment ever arises. The erosion of the rule of law tends to lead to arbitrary power, which aligns with the classical liberal definition of tyranny.

This lesson holds particular significance for Americans, given the unique success of the American Revolution, which may foster a misguided belief that the rule of law can be easily restored if it falters. In contrast, many European nations have witnessed repeated breakdowns of the rule of law in recent history; over the last seventy-five years, numerous countries have oscillated between autocratic regimes, not to mention the upheaval of the French Revolution in 1789. Each restoration of the rule of law was fraught with difficulty and, arguably, only partially successful. The establishment of the European Union aimed to reinforce the rule of law, despite its notorious bureaucracy and overreach. However, it can be contended that the EU has, indeed, shielded its member states from overt forms of tyranny for several decades.

Historically, it was assumed that the rule of law was more robust in America than elsewhere. Today, however, it appears that the rule of law faces its most significant threats within the United States. Many Americans remain oblivious to this reality, mistakenly believing that the path to tyranny closes when a strongman of their liking is in charge. We must not forget that despotism is a potential reality here as well.

Even in its imperfect state (which is not merely a façade of legality), the rule of law is preferable to unrestrained arbitrariness, albeit with two critical caveats. First, the rule of law must permit a certain level of principled civil disobedience, but this should originate from the governed, not those in power. Second, revolution may be justified when it is necessary to dismantle a tyrannical regime and establish the rule of law, rather than merely replacing one arbitrary rule with another.

So, how can we preserve the rule of law? A universally acknowledged condition, deeply rooted in the classical liberal tradition and institutional economic analysis, is the independence and security of judges. Up to a certain point, judicial decisions can be appealed, but until that moment, one judge has the power to halt the machinery of a powerful state. (Refer to Bertrand de Jouvenel’s On Power.)

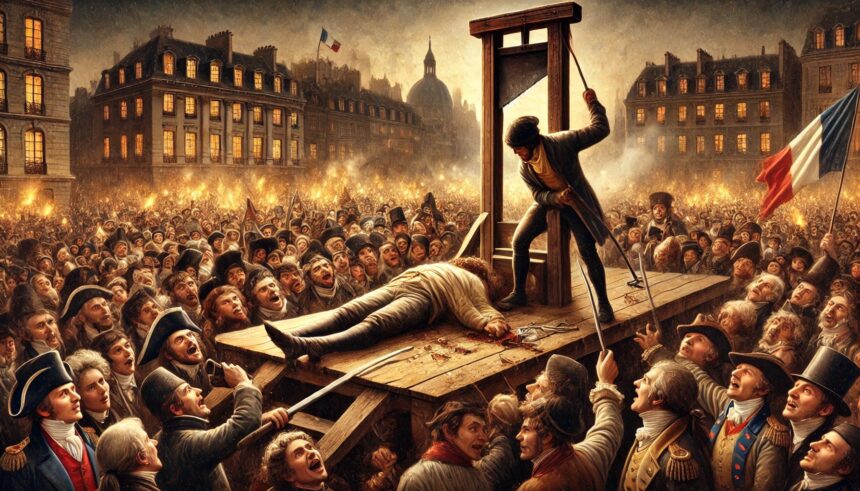

This requirement is paramount, despite a White House deputy press secretary’s declaration that “rogue judges are undermining the will of the American people.” One could wager she hasn’t delved into Jean-Jacques Rousseau and lacks insight into her assertions, yet her comments reveal the prevailing atmosphere. If, or when, the “will of the people”—a phrase invoked by several high-ranking officials against independent courts—turns against them, one judge could be the bulwark standing between them and “the people.” History is replete with examples. Had there been independent courts, Maximilien Robespierre, once a popular revolutionary leader, could have sought judicial protection before his execution by guillotine on July 28, 1794, amid a clamoring mob in Paris.

******************************

“Robespierre guillotined,” by DALL-E (with numerous historical and technical incongruities)