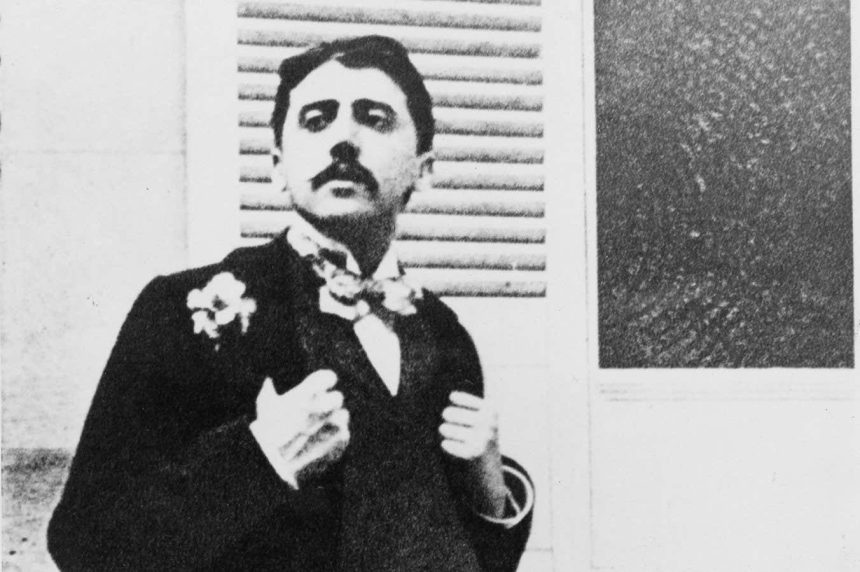

Marcel Proust, captured in 1905

Photo 12 / Alamy

As dawn gracefully unfolded in the city, shadows began their slow retreat, allowing the gentle light of a new morning to emerge. It was June, and the few individuals awake—preparing market stalls—savored the tranquil glow of daybreak, their minds briefly at ease despite the distant threat of an enemy just fifty miles away. While many wealthy residents had already left the city, most clung to optimism that the defensive lines, held steadfast for nearly four years, would endure. There remained a flicker of hope.

Along Boulevard Haussmann, a handful of vehicles traveled eastward, creating a serene atmosphere as the street remained largely silent, its residents still caught in slumber. Yet, the individual occupying the second-floor apartment at number 102 had been awake for quite a while—throughout the night, in fact. The thick shutters covered his windows, sealed shut for months. The only illumination in his dimly lit chamber derived from a green bedside lamp. The room, filled with dark furnishings and a desk overtaken by towering stacks of books, was thick with the pungent fumes of stramonium, used to alleviate his asthma, creating a stifling ambience. The cork-lined walls had been specifically designed to muffle the sounds from both the street and the rest of the building, intensifying the claustrophobic atmosphere that most visitors likely felt.

Propped up against two large pillows in his ornate Japanese housecoat, he usually would have been engrossed in his manuscript at this hour, furiously writing by hand in black leather notebooks—a labor he had diligently pursued for twelve years. However, this particular morning, he was consumed by anxiety. He suspected one side of his face was drooping. After conversing with his housekeeper, Céleste, the previous evening, he had been certain that his speech was slurred, his words somehow jumbled. He feared that a significant stroke awaited him, just as his parents had endured. It ran in the family, after all. His beloved mother, Jeanne, had suffered greatly; her stroke deprived her of language entirely, leaving her aphasic and incapable of conversing with her cherished sons.

Thus, in the summer of 1918, with the German forces mounting their final offensives of World War I aimed at Paris, the eminent novelist Marcel Proust found himself enveloped in deep contemplation amidst his blue satin sheets. He harbored a profound dread of losing his ability to communicate due to a potential brain disorder. Now in his late forties, he was acutely familiar with the implications of aphasia. Not only had his mother battled it, but before experiencing his own stroke, his father, Dr. Adrien Proust, authored a comprehensive book on the subject.

Throughout his younger years, Marcel had crossed paths with many esteemed neurologists in the city. At that time, Paris was revered as the forefront of research on brain disorders, boasting pioneering experts who made significant contributions to understanding language disorders post-stroke—conditions that could impede not just speech but also reading and writing abilities. Without these essential faculties, where would Proust find himself?

On this fateful June morning of 1918, the dread of imminent aphasia compelled him to schedule a consultation with the renowned neurologist Joseph Babinski, just a ten-minute walk away at number 170 on the same boulevard. Reflecting on the encounter, Proust recalled that Babinski was entirely unfamiliar with him. ‘Do you have a job?’ Babinski had reportedly inquired.

On that fateful day, Proust aimed to persuade Babinski to undertake trepanation—drilling a hole in his skull. His fear was so profound that he believed such a drastic measure was necessary to thwart the advance of a stroke. Babinski, ever the professional, thoroughly assessed Proust and reassured him that no signs indicated a stroke’s onset, gently declining to carry out the procedure. One can only speculate how Proust’s monumental novel might have been affected had he gone through with it. Ultimately, Proust never suffered a stroke, yet the anxiety of a potential stroke, which would haunt him for the rest of his relatively brief life, persisted. Even as he battled pneumonia a few years later, it was still Babinski who was summoned for assistance.

Concerns over brain-related conditions similar to Proust’s are not uncommon. While anyone can encounter ailments affecting the body, many harbor an especially deep fear of disorders impacting the brain. Why is this? Because neurological issues can fundamentally alter one’s personality. Some individuals may be rendered unable to communicate, just as Proust had dreaded. Others could experience memory loss, distorted perceptions, or hallucinations. Some may act inappropriately socially, exhibiting diminished empathy or aggressiveness. Others might become impulsive or lack inhibition, risking significant financial losses or developing new dependencies. Pathological apathy can also manifest, resulting in withdrawal and lack of motivation to engage with others.

Such shifts in behavior and personality can understandably distress not only the individuals affected but also their families. Yet, these changes also offer profound insights into human nature. By examining what occurs when specific brain functions are compromised, we glean valuable information about our own selves, how cognitive abilities factor into forming our identities (both personal identities and social identities) which derive partly from our interactions with others.

For an individual like Marcel Proust, the loss of language would have been devastating. Not only would he be stripped of his ability to write, but he would also lose his status within his social sphere. The meticulously cultivated social identity he had worked tirelessly to establish would likely dissolve. For years he had nurtured connections with some of the most influential figures in French society, meticulously navigating the complexities of prejudice and snobbery, especially as a gay man of Jewish descent (from his mother’s side).

Through observation and imitation, he seamlessly integrated into a circle where few would have anticipated he would find acceptance or exert influence. Some experts have suggested that Proust was a masterful manipulator, unwilling to relinquish his sway over those in his vicinity, despite spending long hours isolated in his dark bedroom. Yet without his ability to communicate, the elite networks he had strived to join would no longer be within reach. He would no longer ‘belong.’

This is an excerpt from Masud Husain’s Our Brains, Our Selves (Canongate Books), winner of the Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize and the latest selection for the New Scientist Book Club. Sign up and read along with us here.

Topics: