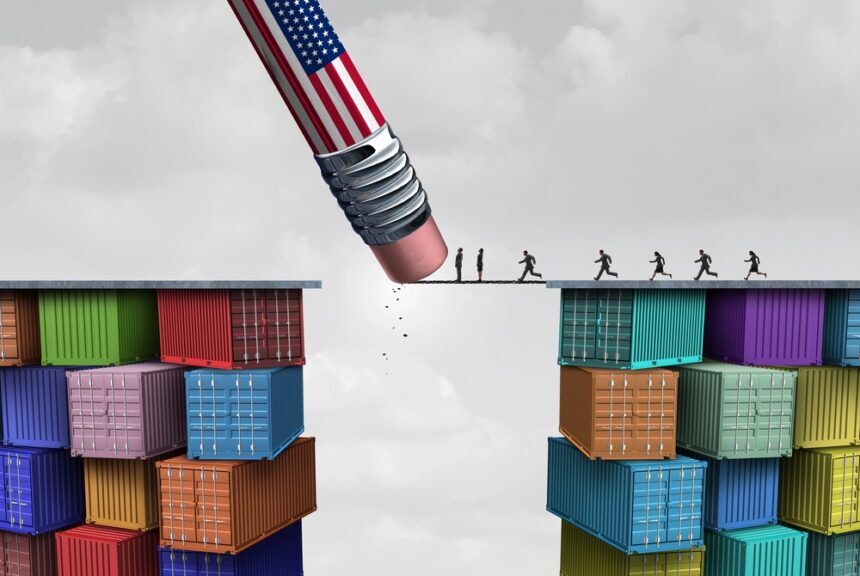

Welcome back to the peculiar universe of “Kevin’s critiques on economists’ naming conventions.” Today, let’s tackle the term “trade deficit” and consider a fresh perspective on its branding.

The root of the misunderstanding lies in the term itself—deficit. When we hear “deficit,” it conjures images of overspending and debt accumulation. This is certainly true in the realm of personal finance: if my household budget is running a deficit, it suggests I’m either maxing out my credit cards or borrowing from friends. Sure, a temporary budget shortfall can happen—perhaps unexpected medical bills—but if that pattern persists, we’re heading for a financial train wreck.

However, a nation running a trade deficit is not the same as a household drowning in debt. Let’s consider a practical example: Nintendo’s announcement of its new console, the Nintendo Switch 2, priced at $449. When I decide to purchase this console and transfer that amount from my checking account, the trade deficit increases by $449. Yet, this transaction doesn’t entail any indebtedness. No one is living beyond their means; it’s merely a mutually beneficial exchange—something that, if we are to believe former President Trump, might be misconstrued as Japan “ripping us off.” But in reality, it’s just a straightforward transaction.

In light of this, I propose we rebrand “trade deficit” to something like consumption surplus. In 2024, the United States registered a trade deficit of around $918 billion. While the U.S. exported about $3.2 trillion worth of goods and services, it enjoyed consuming approximately $4.1 trillion worth of goods and services from abroad. Essentially, we benefitted from consuming $918 billion more than we gave up. As President Trump might quip, that’s a lot of winning!

(Admittedly, the term “consumption surplus” is also somewhat misleading, as over 60% of U.S. imports are inputs for production rather than direct consumer goods. Nevertheless, it feels less misleading than the existing terminology.)

On a related note, Scott Sumner recently emphasized that when considering all aspects of trade (goods, services, and financial assets), trade balances out. A trade deficit, or more accurately, a current account deficit, is always counterbalanced by a capital account surplus, which tracks savings and investment. Thus, if the U.S. had a current account deficit of $918 billion last year, it also had a capital account surplus of the same amount. The funds not spent by foreigners on American goods and services are redirected into savings and investments—whether through purchasing dollar-denominated assets, foreign direct investments in U.S. firms, or bonds.

(Let’s entertain an extreme scenario where, instead of investing those $918 billion, foreigners decide to convert it to cash and burn it. Even in this bizarre case, the outcome isn’t catastrophic. This bonfire would merely reduce the amount of U.S. dollars in circulation, thereby increasing the value of the remaining dollars held by American citizens. So, even under such a ludicrous scenario, the value represented by that $918 billion would return through heightened purchasing power.)

By adopting this new terminology, American citizens can appreciate not only the benefits of a consumption surplus but also the corresponding investment surplus. I believe this reframing could resonate with President Trump—if only he’d pick up the phone and give me a call. One can only hope he stumbles across this blog!