Swiss Scientists Develop Revolutionary Living Fiber Material

A team of Swiss scientists from Empa have unveiled a groundbreaking new material that is not only flexible and biodegradable but also edible. What sets this material apart is that it is alive, derived from the mycelium of the split-gill mushroom.

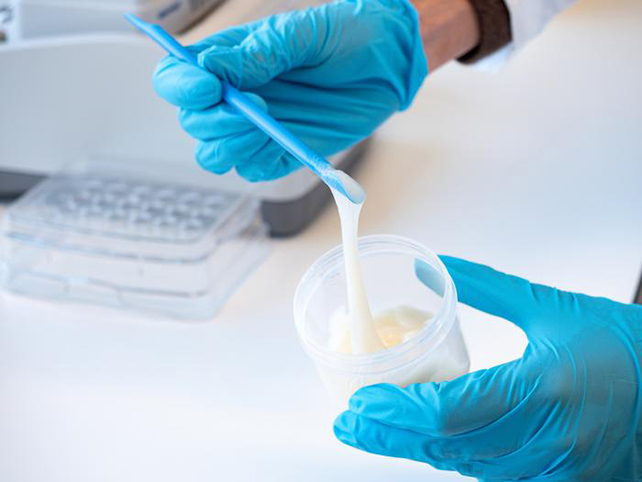

Known as living fiber dispersions (LFD), this gel-like substance retains the natural biological functions of the mycelium, providing a sustainable and versatile alternative to traditional plastics. By processing mycelium fibers into a liquid mixture, the researchers were able to harness the unique properties of the split-gill mushroom without harming its structure.

The key to the material’s success lies in the cultivation of specific molecules within the split-gill strain, namely polysaccharide schizophyllan and hydrophobin. These compounds give LFD its strength and adaptability, making it suitable for a variety of applications.

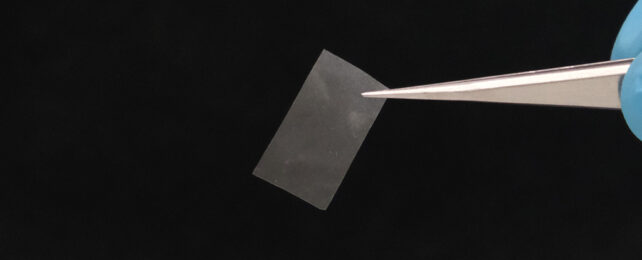

One potential use for LFD is as a thin film with high tensile strength, ideal for compost bags and biodegradable batteries. Additionally, the material functions as an emulsifier, enabling it to blend with other substances and enhance stability over time.

Given its origin from the edible split-gill mushroom, LFD is completely non-toxic and can be safely consumed. This opens up possibilities for its use in food and cosmetic industries, where biodegradability and safety are paramount.

The researchers believe that LFD can be further manipulated to create materials with specific properties, paving the way for customizable and sustainable solutions. As the demand for eco-friendly alternatives grows, fungi-based biomaterials offer a promising avenue for innovation.

Published in Advanced Materials, this research showcases the potential of nature-inspired materials in addressing environmental challenges. By harnessing the natural properties of fungi, scientists are pushing the boundaries of sustainable material design.

“Biodegradable materials always react to their environment,” explains materials scientist Gustav Nyström. “We want to find applications where this interaction is not a hindrance but maybe even an advantage.”