Using Mindfulness Meditation for Pain Relief: A Closer Look

If you’re in a lot of pain, being told to take deep breaths and accept the sensations in your body might not feel particularly comforting.

But new research analyzing pain signatures in MRI scans suggests mindfulness meditation as pain relief goes beyond the placebo effect of expecting a response – it actually produces a very real reduction in pain.

Mindfulness meditation is when a person practices sustaining awareness of sensory events as they drift by, without judging or resisting them. It originated in Hindu and Buddhist traditions, but ever since hitting Western pop culture in the 1970s, the practice has been gaining increasing attention from those in the Western scientific discipline.

“The mind is extremely powerful, and we’re still working to understand how it can be harnessed for pain management,” says anesthesiologist Fadel Zeidan, from the University of California San Diego (UCSD).

“By separating pain from the self and relinquishing evaluative judgment, mindfulness meditation is able to directly modify how we experience pain in a way that uses no drugs, costs nothing and can be practiced anywhere.”

UCSD neuroscientist Gabriel Riegner, Zeidan, and colleagues sought to disentangle the brain’s distinct signatures of pain, and determine if the pain-killing effects of mindfulness meditation were, as they suspected, more than just placebo.

They enlisted 115 healthy participants who were split across two separate clinical trials. In both, the researchers touched the back of each participant’s right calf with a heated probe, which produced waves of painful but harmless temperatures.

Participants’ brains were scanned using MRI before and after the experiments, and they self-rated their pain intensity and unpleasantness on a 0–10 pain scale.

Ahead of these studies, some of the participants were trained in mindfulness meditation by experienced instructors across four separate, 20-minute sessions, learning to focus on their breath’s changing rhythms and to acknowledge thoughts, feelings, and emotions that might arise without reaction or judgment.

Another group was given an equivalent sham-mindfulness meditation that consisted only of deep breathing, and others were given a placebo cream of petroleum jelly, which they were told would reduce pain.

A further group used as a control listened to an audiobook in place of the meditation instruction. This was The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, written by 18th-century parson-naturalist Gilbert White.

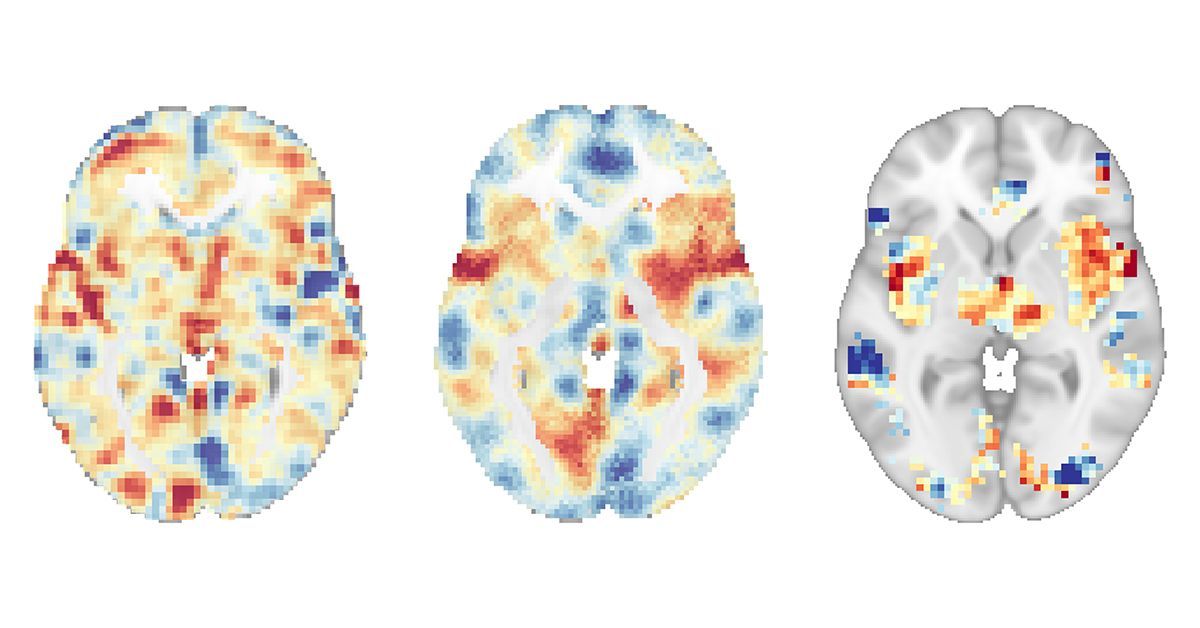

The MRI scans offered the researchers data on a variety of pain signatures, including: the nociceptive-specific pain signature (NPS), associated with pain intensity; the negative affective pain signature (NAPS), associated with the emotional experience of pain; and the stimulus-independent pain signature (SIIPS-1), which is related to psychosocial factors, like our expectations of pain, and thus identifies placebo-based dimensions.

The mindfulness meditation produced a greater reduction in self-reported pain and in NPS and NAPS compared to the placebo and controls, but the only treatment to produce a significantly lower response in the placebo-based signature, SIIPS-1, was the placebo cream.

This suggests the positive effects of mindfulness meditation were based on mechanisms other than placebo: If there was overlap, the meditation intervention should have produced a significant effect on SIIPS-1.

“It has long been assumed that the placebo effect overlaps with brain mechanisms triggered by active treatments, but these results suggest that when it comes to pain, this may not be the case,” says Zeidan.

“Instead, these two brain responses are completely distinct, which supports the use of mindfulness meditation as a direct intervention for chronic pain rather than as a way to engage the placebo effect.”

The team hopes these findings can help guide treatment for the millions of people who live with chronic pain every day, and improve their quality of life.

“We are excited to continue exploring the neurobiology of mindfulness and how we can leverage this ancient practice in the clinic,” Zeidan says.

This research is published in Biological Psychiatry.