This investigation was initially shared by The Plumas Sun and Bay Nature, a nonprofit news source aimed at deepening the connection between residents of the San Francisco Bay Area and the natural world.

A white-headed woodpecker breaks the morning silence, tapping at a patch of scorched bark that extends 15 feet up a ponderosa pine tree. As the first rays of sunlight illuminate the tree’s verdant top, they bounce off the grove of thriving conifers. The remnants of the 2021 Dixie Fire can be seen all around. A number of charred trees lie downed among the pale blossoms of deer brush and the spikes of snow plant, their once vivid hues now muted to a dusky coral.

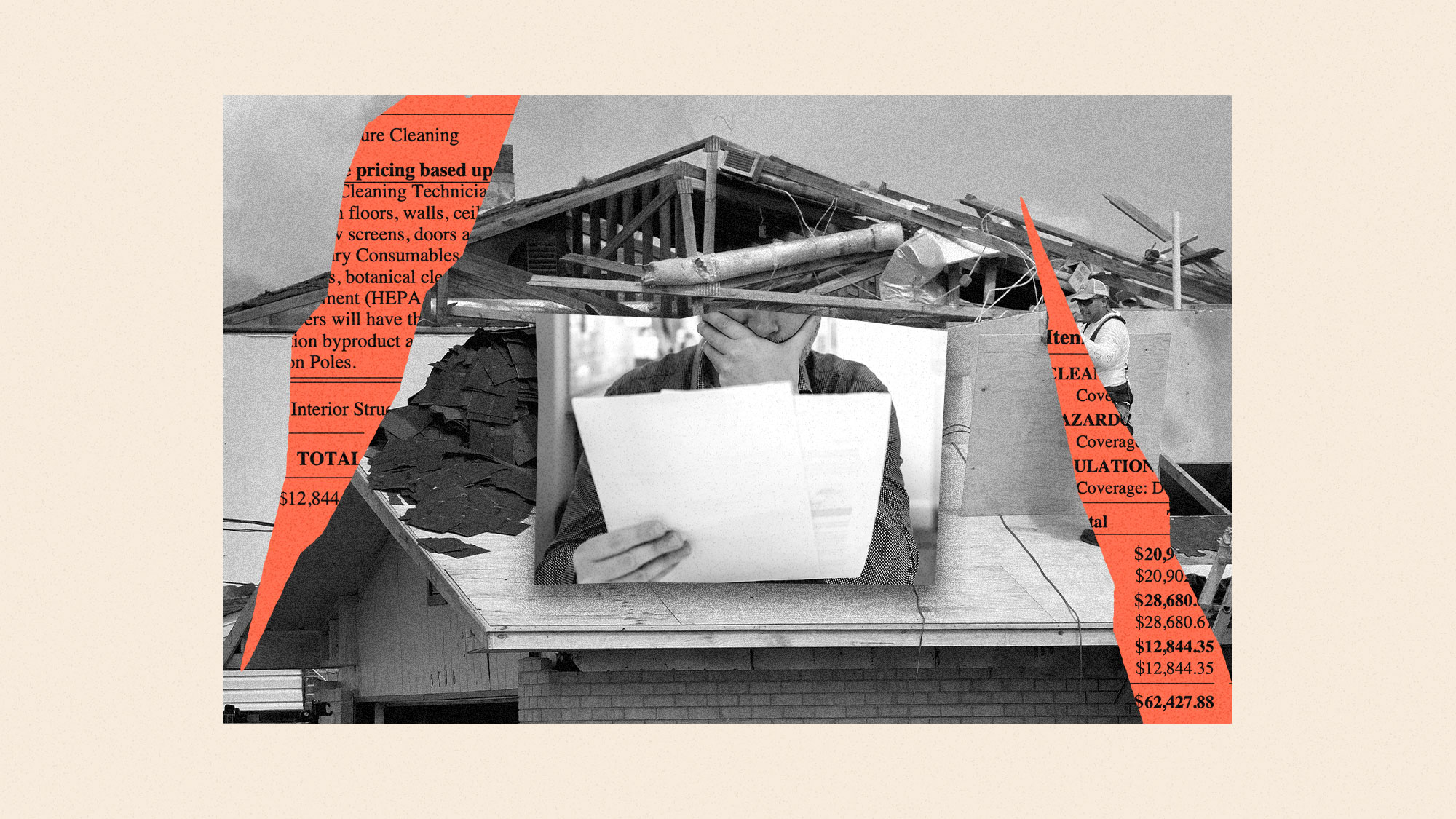

Fires raged through adjacent forests, blowing apart treetops and casting sparks down the mountainside. On August 4, 2021, the flames finally reached the valley below, devastating Greenville, located 90 miles north of Lake Oroville. In a mere thirty minutes, a town of 1,000 residents was obliterated. Nonetheless, this stand near Round Valley Reservoir remained intact.

Years prior, U.S. Forest Service crews had cleared away brush and smaller trees, minimizing the most combustible vegetation. They then initiated controlled burns to eliminate remaining ground debris. When the Dixie Fire arrived, despite its ferocity that melted vehicles and burned 800 homes, it merely skirted this stand, meandering along the forest floor with just occasional flickers up the trunks of trees, explains Ryan Bauer, who served as the Plumas National Forest fuels manager for 18 years.

Bauer wishes there had been more active forest management of this kind. “Instead of just burning 100-acre patches, if we had burned areas of 10,000 acres, we’d be looking at 10,000 acres of surviving forest. We simply never did that,” says Bauer, who has since retired and is collaborating with a nonprofit to help communities adapt to fire hazards.

In the last seven years, two-thirds of the Plumas National Forest has burned, an expanse twice the size of San Francisco Bay. These fires have sent plumes of smoke rushing down the Feather River Canyon, across the Central Valley, and into the San Francisco Bay Area, casting the sky in a burnt orange hue. Each fire has taken a toll on the watershed that supplies drinking water to more than 27 million Californians. With each conflagration, habitats for deer, bald eagles, and four of the state’s ten wolf packs hang precariously in the balance.

While the rest of the Plumas Forest remains lush, it is dangerously overcrowded, with trees now six to seven times denser than in earlier times, according to a 2022 study led by noted fire scientist Malcolm North. As forests dry each summer—a trend exacerbated by climate change—vegetation becomes increasingly susceptible to even the smallest spark, primed to ignite into the catastrophic wildfires experts insist are likely unless there is a substantial uptick in active forest management. If the Plumas Forest burns, the 8,000 residents in towns like Quincy, Graeagle, and Portola will face grave risks, poised to join thousands already displaced from Paradise, Greenville, and other communities devastated by recent wildfires.

The forest is also at existential risk, according to Michael Hall, manager of the Feather River Resource Conservation District. The Sierra Nevada forests have evolved alongside fire, relying on its ability to clear overcrowded trees and allow nourishing sunlight to reach the ground, fostering new growth. Species like black-backed woodpeckers, morels, grasses, ferns, and wildflowers all depend on episodic wildfires for survival. A century of fire suppression has hindered this natural cycle, leading to congested and unhealthy stands that have fueled the recent outbreak of mega-fires. Hall warns that if we do not address the threat posed by such fires, we risk destroying the soil and seed banks that restore forests, which in turn could result in trees transforming into shrubs and snags, and some ponderosa and red fir forests might shift to oak and brush. Without efficient management, these too will ignite. “Then we’ve lost a forest,” he cautions. This alarming scenario has spurred Forest Service officials into action.

In response to research findings, officials in the Plumas National Forest have initiated a plan promoting significant changes in forest management. To implement this, they are deploying chainsaws, drip torches, and an extensive range of machines including masticators, feller bunchers, grapples, and hot saws. The objective is to thin, log, and intentionally burn what experts classify as hazardous forests. If their efforts can stay ahead of potentially devastating fires, they aspire to maintain a substantial expanse of trees that are resilient against future conflagrations. This initiative, aimed at 285,000 acres of forest, is called Plumas Community Protection, and in 2023, Congress allocated $274 million to facilitate its execution.

This initiative is ambitious and visionary, yet remains untested at this scale. Its success hinges on swift action from a government bureaucracy not known for agility, particularly under an administration that has seen significant layoffs and frozen millions in federal funds.

Despite the high stakes, Forest Service officials have had very few public engagements, providing scant project details to journalists and declining to review a synopsis of our findings. Bay Nature and The Plumas Sun largely conducted their reporting without input from federal personnel, including public information officers who expressed concerns that fulfilling their roles could jeopardize their jobs. Consequently, we interviewed 47 experts from various agencies, nonprofit groups, and community leaders, as well as examined public records, to construct a detailed understanding of the Plumas Community Protection project thus far.

Our interviews clearly indicate that despite the funding, which was beyond imagination five years ago, much of it has already been allocated or spent. Nonetheless, tangible efforts on the ground have been minimal, and the plan appears to be faltering.

Hail Mary Plan

Residents of Plumas County can recount the recent sequence of fires chronologically starting from 2017: Minerva, Camp, Walker, North Complex, Dixie, Beckwourth Complex, Park… Each name evokes anxiety. The 2021 Dixie Fire inflicted the most severe damage, ravaging the communities of Canyon Dam, Greenville, Indian Falls, and Warner Valley as it surged through the Feather River Canyon and into Lassen Volcanic National Park, reaching Hat Creek. When the winds finally calmed and crews extinguished the flames that October, the Dixie Fire had scorched nearly one million acres, marking California’s largest single fire on record. For those who evacuated and lost their homes, businesses, and livelihoods, time is permanently divided into before and after, pre-fire and post.

In the ensuing months, stunned officials from the Plumas Forest confronted a troubling truth. For decades, they had focused on timber sales and tree marking aimed at fulfilling targets set by Washington, D.C., while aggressively suppressing every fire. By the 1990s, they recognized that this approach was leading to increasingly intense wildfires. Consequently, they developed a network of fuel breaks—straightforward strips devoid of vegetation—to hinder fire spread.

The fuel break near Round Valley stood as one of the few successful examples within Plumas Forest. The Dixie Fire vastly overwhelmed most others, along with several related projects. “They were simply outmatched by a fire of an unprecedented scale,” shares Angela Avery, executive director of Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state-funded conservation agency. The devastating impact of the Dixie Fire made it clear that traditional approaches were inadequate to safeguard the Plumas Forest and surrounding communities. “We did everything we could but were powerless to stop it,” adds Bauer, the former fuels manager.

Bauer, a Portola High School alumnus from 1994, became intrigued by fire’s role in ecosystems during a forestry class. Throughout his 31-year career in the Forest Service, he focused on reintegrating fire into landscapes. As the smoke from the Dixie Fire settled, Bauer recognized a pivotal opportunity, initiating fresh plans in collaboration with regional Fire Safe Councils and community wildfire readiness organizations. They concentrated on towns within the Plumas Forest that had yet to experience wildfire damage. Their plans aimed at enhancing community security and forest resilience to drought, pests, and other climate-related disturbances. Community defense became the foremost priority, while forest resilience took second place. Strategies included establishing buffer zones up to a mile wide surrounding communities at the wildland urban interface (WUI).

Bauer’s initial rough strategies were refined into plans that serve as the foundation for the community protection initiative. The long-range objective is to prepare the unburned forest areas for future fires, enabling them to clear out combustible underbrush that could lead to destructive wildfires. The plans broaden the buffer zones around WUI areas and significantly extend the land designated for thinning and logging. Most importantly, the plans stress the necessity of conducting prescribed burns regularly throughout the forest. No thinning or commercial logging operations are complete until they are followed by intentional burning, Bauer states.

Working alongside his Fire Safe colleagues, Bauer identified 300,000 acres marked by dense brush and overcrowded trees posing a threat to both communities and environmental resources. Forest officials began conducting biological, archaeological, and watershed assessments while also streamlining the environmental evaluations they would need moving forward. Forest planners usually work ahead of funding, but this 300,000-acre initiative lacked guarantees for approval or financing. “This was quite the gamble,” Bauer admits. “We often take risks, but this one was significant.” This gamble targets the preservation of 41 rural communities and the national forest directly in the firing line of likely wildfires in the aftermath of the Dixie catastrophe.

A Whopping $274 Million

The ferocity of the Dixie Fire and other mega-fires in 2020 and 2021 astounded officials within the Forest Service in Washington, D.C. The following year, a wildfire crisis approach was revealed, designating 45 million acres, primarily in the West, as particularly high-risk “firesheds.” Congress allocated $3.2 billion through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) to enhance safety in these regions. In January 2023, Plumas National Forest’s 285,000 acres were included in this initiative. The staggering $273,930,000 funding highlighted the urgency felt from Quincy to the nation’s capital. The allocation for Plumas Forest comprises roughly 20 percent of the $1.4 billion in federal BIL and IRA expenditures for natural initiatives in Northern California that Bay Nature has monitored in its Wild Billions tracking project, standing out as the largest single investment by far.

Such a substantial commitment to forest health across this vast landscape is monumental, remarks Chris Daunt, a resident of Portola and member of the Mule Deer Foundation, which garnered $14 million for hands-on treatments. He refers to it as “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”

Efforts rapidly transitioned to identifying specific geographic areas primed for thinning and logging to pave the way for beneficial fires safeguarding communities. Initial work commenced in Quincy, the county seat, which was subsequently incorporated into the Community Protection project. The focus then shifted to Portola, Graeagle, and a series of small towns lining Highway 70, where planning efforts were already in motion. Forest officials earmarked $85 million from the federal funds for Sierra Tahoe Environmental Management, a logging firm based in Loyalton, which was established around the time the well-financed Plumas plan was launched. The company is tasked with removing hazardous trees across 70,000 acres, selecting those substantial enough for commercial logging and, ultimately, applying intentional fire. The Montana-based nonprofit National Forest Foundation (NFF) received $98 million to accomplish similar tasks on another 70,000 acres in the valley surrounding Quincy and Mohawk Valley to the east.

Bigger, Faster

The sheer scale of the Plumas Forest projects is unprecedented. Each of the two 70,000-acre initiatives far exceeds the size of most prior contracts in the Plumas region, on a considerably larger scale than what has traditionally been undertaken in California. “This is the caliber of effort we must pursue,” asserts Jason Moghaddas, a Quincy-based forester, fire ecologist, and geographic analyst knowledgeable about the Plumas National Forest.

Larger scope is the main objective, emphasizes Avery from the Sierra Nevada Conservancy. Inspired by the vastness of modern wildfires, the Conservancy has financially supported landscape-scale initiatives. “If a mega-fire or a fire igniting over a million acres occurs, we stand more chance of combating it, with treatments showing efficacy,” she explains. Plumas Forest officials have devised thinning projects that increased in size from 5,000 acres to 50,000 and prescribed burns that would encompass most of the Plumas Community Protection area.

The immediate threat of wildfire prompted Plumas Forest officials to expedite the environmental evaluations necessary under the National Environmental Policy Act. Rather than conducting thorough environmental impact statements, which involve scrutinizing cumulative impacts and time-consuming public comment periods, officials opted for less demanding environmental assessments. Emergency declarations allowed for fast-tracking work on at least 70,000 acres, thereby removing public objections. NEPA processes that could typically span seven years averaged around 20 months in this case.

This approach has drawn some criticism, with two environmental organizations filing a lawsuit against the Forest Service for neglecting a “thorough and meaningful” review of the environmental ramifications. Consequently, Plumas National Forest officials temporarily withdrew approval for over half of the targeted landscape, stalling implementation for more than a year to revise their environmental analysis, which was released on July 1.

Nevertheless, nearly all 47 interviewees contended that expediting procedures is warranted given the imminent risk of catastrophic fires. The challenge is whether they can execute the necessary work swiftly and effectively enough to mitigate some of the disastrous outcomes we’re witnessing. “It’s a complicated situation,” admits Jonathan Kusel, executive director of the Sierra Institute for Community and Environment, which has assisted with the environmental evaluations for Plumas Forest.

Recent scientific analyses bolster both the proposed scale and urgency of the Plumas efforts, according to Scott Stephens, a fire science professor at UC Berkeley. There are calls for even more extensive work on greater areas. “If anything, the Plumas Community Protection project does not address enough land,” Hall and others stated in a published commentary.

What’s Done

Navigating through Plumas County, where 90 percent of the land is federally managed, one observes stretches of lush forest contrasting starkly with extensive charred areas, the remnants sometimes visible even to the horizon. Between Quincy and the isolated mining settlement of La Porte, a thriving expanse of red fir and the fragrant Jeffrey pines dips toward the Middle Fork of the Feather River, its muffled cascade audible from a thousand feet above. The high-pitched calls of Townsend’s solitaires disturb the serenity.

This dense woodland represents some of the dangerously overcrowded areas slated for thinning, logging, and prescribed fire. Two years after Congress allocated the $274 million, progress in the forest has remained slow. Advancements toward treating the targeted 74,000 acres in 2023, and a total of 185,000 acres in subsequent years, has been incremental.

Some work has commenced. In regions around Quincy and Meadow Valley, as well as near communities along Highway 70 to Portola, mastication machines have been processing brush and small trees into wood chips, returning them to the landscape. Crews are also employing chainsaws and other equipment for thinning operations. These efforts are initial steps before commercial logging, which has yet to begin.

The Forest Service’s annual reports indicate that 49,496 acres in Plumas Forest were treated in 2023 and 5,400 acres in 2024, which comprises roughly one fifth of the overall objective. However, the actual progress toward enhancing forest safety remains unclear. The reports fail to categorize whether treatment was due to thinning, logging, or prescribed burning, nor can they specify locations of the activity. The broader question of how to measure forest resilience and community protection has generated contention among scientists and forest managers throughout the western U.S. Simply counting acreage is insufficient, says Bauer. A more effective metric would account for when all necessary groundwork has been completed on an acre, suggests Eric Edwards, whose research at UC Davis focuses on environmental and agricultural economics.

For all the hype surrounding the wildfire crisis strategy’s emphasis on intentional burning and its protective advantages for both forests and communities, the Plumas Community Protection plan lacks clarity regarding acreage goals and the enforcement of contractor burn objectives. It designates all 285,000 acres for prescribed fire, claims Bauer. Yet, unlike thinning and logging operations, contractors are not bound by specific burn targets. “It’s often a soft commitment,” he says. Plumas Forest officials have reported that 2,543 acres have been burned since October, primarily from burning piles of branches and brush, which does not encompass the crucial low-intensity intentional fires meant to travel across the forest floor. Estimates by Bay Nature and The Plumas Sun suggest that only about 2,500 acres underwent the necessary intentional burning, totaling just under 1 percent of the intended landscape.

The Forest Service reports about the national wildfire crisis strategy have highlighted various hurdles to implementation, including elevated costs, a shortage of timber markets for small-diameter wood, high employee housing costs, uncompetitive salaries, and restricted on-the-ground capacity.

Information regarding progress on the Plumas Community Protection projects has primarily not come from officials in the Plumas Forest, who have largely ignored media inquiries since late January. Attempts to reach the Plumas Forest supervisor’s office have often led to unanswered calls, some resulting in strange recordings of the Smokey Bear song. Written queries posed to the Forest Service’s public affairs office in Washington, D.C., back in February have gone unacknowledged. The prior administration obstructed press access to agency scientists and removed the interactive map that used to track project progress. The sole interview granted since late January took place in August, focusing solely on utilizing agency data. Links to earlier accessible websites have now returned “page not found” error messages or, somewhat ironically, “Looks like you hit the end of the trail.”

Many Plumas locals assert that the Forest Service has fallen short of its responsibility to keep the public informed. John Sheehan, who has closely monitored Plumas National Forest issues since 1992, expressed his dissatisfaction with being largely uninformed about the Community Protection plan: “When the government is going to undertake such a monumental initiative, especially so close to residential areas, it’s crucial they engage with the affected population. The Plumas Forest remains disengaged.” Josh Hart, a spokesperson for Feather River Action!, a party in the lawsuit brought by environmental groups, echoed his concerns about the lack of public communication pertaining to “the most significant plans for the Plumas National Forest in history.”

The agency has not provided any accounting of the $274 million spent. Public records and conversations with contractors indicate that approximately $202 million has been allocated for thinning and logging. An additional $5 million has been used for prescribed burning, according to Bauer. The Great Basin Institute received around $2 million for wildlife assessments. Approximately $50 million was spent on environmental reviews. This leaves around $15 million unaccounted for; some was likely directed towards salaries, with most spent on planning, Bauer suggests. “That funding source is gone.”

A national report from 2025 acknowledged that the agency had nearly exhausted the majority of its BIL and IRA funds. “Fully realizing the vision specified by the Wildfire Crisis Strategy requires ongoing, sustained investments,” the report notes.

Hamstrung

Two complete years since the launch of the Plumas Community Protection initiative, the Plumas Forest’s reduced capabilities raise concerns about its ability to undertake its own plans. Staff reductions under the previous administration have compounded years of diminished workforce resources. The position of Plumas Forest supervisor remained vacant for over a year. With a revolving door of vacancies and short-term appointments, many partners and contractors find themselves waiting for necessary decisions to advance their work, says Jim Wilcox, a senior advisor for Plumas Corporation, who has been involved with Forest Service restoration contracts for 35 years. “The delays are incredibly frustrating.”

Other agencies and private companies are stepping in to fill some gaps, as part of the national strategy to respond to the wildfire situation. They have taken the lead on many of the required environmental assessments and are slated to undertake much of the actual project work. While the Forest Service has historically engaged outside partners for logging and burning activities, Moghaddas observes that the enormous 70,000-acre units create larger, more complex partnerships. “The Forest Service can’t manage it independently,” he explains. Avery notes that this represents a cultural transformation, stating, “I’ve seen an evolution in the Forest Service’s willingness to collaborate with partners, which I view as a positive response to tragedy.”

The retreat from federal oversight of national forest land has raised concerns for Hall. He comments that crews from the Forest Service have typically been comprised of individuals dedicated to protecting and preserving public lands. “I value the idea of public land and the availability of vast stretches of it… If there are no custodians committed to safeguarding it—and that’s the role of Forest Service personnel—we’ll all face difficulties.”

While STEM is a reputable logging company and NFF is dedicated to preserving national forests, both organizations are new entrants into this field. Ivy Kostick, NFF’s forester for the 70,000-acre project, is methodically segmenting it into manageable portions, explaining, “How does one consume an elephant? One bite at a time.”

Moment of Opportunity

Now, four years after the Dixie Fire, the ambitious Plumas Community Protection plan remains mostly a promise rather than a tangible reality. Since funds have already been committed, substantial work is expected to move forward eventually, as noted by Jake Blaufuss, a lifelong local and a Quincy-based forester for the American Forest Resource Council, which advocates for sustainable forest practices. He observes that commercial logging will generate income, which could be reinvested in prescribed burning and other essential tasks. Jeff Holland, a spokesperson for STEM, suggests that by 2026, noticeable activity will emerge, resulting in visible changes.

For Bauer, the $274 million invested in the plan secured a vital resource: environmental analyses. While the Forest Service has not disclosed specific financial metrics, project partners have confirmed that some federal funds were allocated towards the necessary biological surveys, stream assessments, archaeological investigations, and timber stand evaluations per NEPA requirements. Today, the majority of the Plumas Community Protection landscape is encompassed by a sanctioned plan. Although current on-the-ground activity is limited, when it does begin, Blaufuss remarks that these documents will enable the Forest Service to act more swiftly.

Bauer gauges the initiative’s success by the scope of prescribed fire. Achieving both forest resilience and community protection hinges upon following thinning and logging procedures with burning; this is a goal set within the Plumas Community Protection project. Bauer’s concerns lie with areas surrounding Greenville, where aggressive thinning followed by prescribed burns was planned pre-Dixie. However, most of those areas did not see any chainsaws or drip torches, ultimately being incinerated when the Dixie Fire swept through. “We simply didn’t reach them,” Bauer reflects. If the Plumas Community Protection initiative fails to execute the prescribed burning mandate, “it becomes a game of chance,” he warns. So far, that does not seem to be happening.

Nevertheless, the initiative has fostered an increased understanding of the necessity of fire for both forest resilience and community safety. Forest managers are innovatively exploring ways to make that happen. The narrative around forest management is evolving.

Fire regenerates forest ecosystems. While the toll of the Dixie Fire on the Plumas region and its communities has been devastating, it has positioned them for renewal—much like silver lupines poised in the seed bank, ready to bloom. If the Plumas Forest project can secure further funding and galvanize sufficient political will, their grand vision for protecting the untouched areas may progress. “We recognize that a comprehensive transformation in our forest management approach is required,” says Blaufuss. “This is our moment.”

Tanvi Dutta Gupta and Anushuya Thapa contributed reporting. This article was supported by the March Conservation Fund.