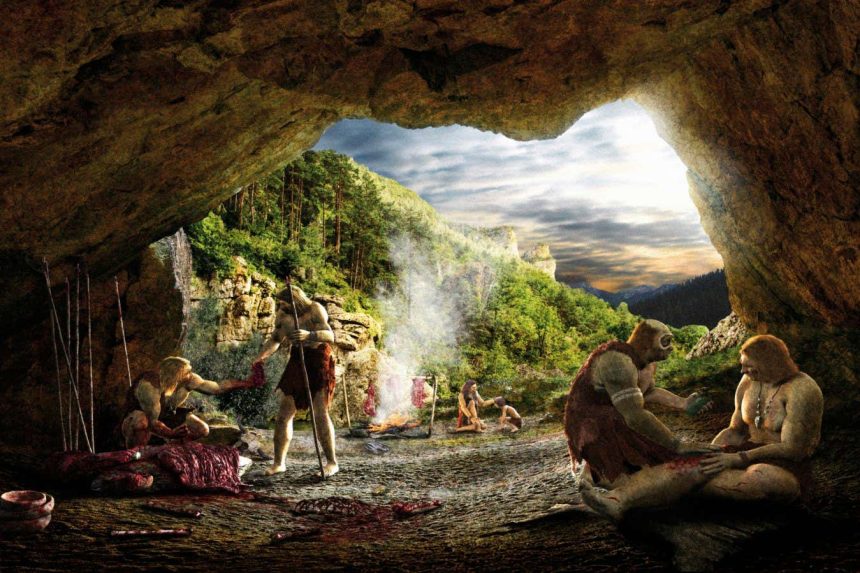

Neanderthals often found refuge in caves

GREGOIRE CIRADE/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

This is an extract from Our Human Story, our newsletter about the revolution in archaeology. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every month.

As winter sets in and the cold creeps into our bones, it’s natural to think of the Neanderthals, our long-extinct cousins. Often portrayed in icy landscapes, recent studies challenge the idea that they were cold-adapted hominins.

Research has shown that Neanderthals may not have had specialized bony structures in their nasal cavities to warm up the air they breathed in, debunking the myth of their cold adaptation. Instead, evidence suggests they may have struggled with the cold just like modern humans.

Recent studies shed light on the environments in which Neanderthals lived, particularly in southern Europe where they survived the longest. Analyses of cave sites and animal remains suggest that Neanderthals inhabited wooded areas with a mix of woodland and grasslands, indicating a climate that was cooler but not frigid.

Southern refuges

Neanderthals, our closest relatives, endured various climatic shifts over hundreds of thousands of years. They thrived in southern Europe, especially the Iberian peninsula, where stable and warmer climates supported their survival.

Studies of micromammals in north-eastern Spain reveal a warm and wet climate between 215,000 and 10,000 years ago, while findings from Lazaret cave in France suggest a woodland environment with herbivores feeding on woody plants.

Discoveries from caves in Spain show a diverse range of bird species, some of which migrated to escape harsh winters. Evidence of Neanderthals hunting these birds is yet to be confirmed, but the possibility of capturing them for food is intriguing.

The last days

As the Neanderthals faced environmental changes, they adapted by altering their behavior. Sites in southern Italy reveal a transition from forest to steppe, prompting Neanderthals to burn more grass in their fires as wood became scarce.

Even in their final days, Neanderthals at sites like Cova Eirós in Spain continued to thrive, hunting red deer and cave bears. The shift towards modern human tool usage suggests a changing landscape with both hominin species coexisting.

Studies of pollen samples from the western Mediterranean seabed indicate a drier climate around 39,000 years ago, coinciding with a decline in Neanderthal tool sites and the emergence of modern human tools. Neanderthals may have persevered in southern regions but ultimately succumbed to the encroachment of modern humans.

Despite their eventual extinction, the Neanderthals’ cultural practices provide clues to their complex lives. Evidence of intentional burials and possible funerary cannibalism suggests a diverse range of mortuary practices, with the Iberian Neanderthals showing variability in their treatment of the dead.

While the Neanderthals may have disappeared, their genetic legacy lives on in modern humans, hinting at a shared history that continues to shape our understanding of our ancient relatives.

Topics:

- Neanderthals/

- ancient humans