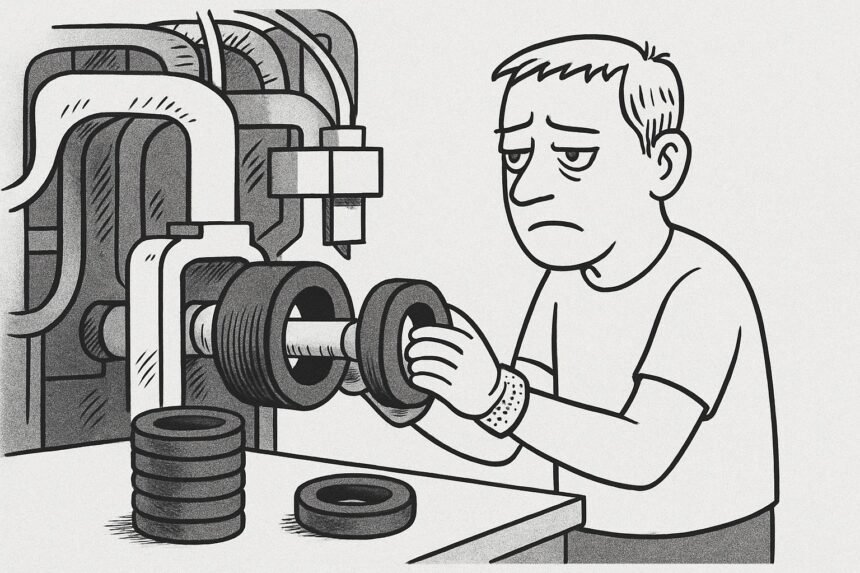

In a brief eight-second clip from the Wall Street Journal, we are presented with a nostalgic glimpse of labor-intensive manufacturing that some, including the last two U.S. presidents, aim to resurrect in America through state intervention and tariffs. The video showcases a worker repetitively operating a machine, under the employment of an Ohio manufacturer eager to ramp up production—and prices—thanks to the hefty 145% tax that Donald Trump imposed on Chinese imports (Trump’s Tariffs Are Lifting Some U.S. Manufacturers, May 4, 2025).

This monotonous task epitomizes the outdated, labor-intensive, and often perilous manufacturing jobs that have been largely phased out in the U.S. and other affluent nations, primarily due to automation and the comparative advantages enjoyed by developing countries with lower labor costs. The push to reinstate such antiquated manufacturing jobs not only misallocates resources from sectors with higher productivity and better wages but also risks creating a situation where employment does not increase, given that the labor market is already near full capacity. Ironically, the very measures designed to bring back these jobs—like tariffs—could exacerbate the employment scenario, introducing problems rather than solving any existing ones.

On the topic of tedious manufacturing roles that once flourished in wealthier countries, Adam Smith noted in his The Wealth of Nations (Book 5, Chapter 1):

“The man whose whole life is spent in performing a few simple operations, of which the effects are perhaps always the same, or very nearly the same, has no occasion to exert his understanding or to exercise his invention… He naturally loses, therefore, the habit of such exertion, and generally becomes as stupid and ignorant as it is possible for a human creature to become.”

He further observed that in a civilized society, this is the fate that befalls the laboring poor unless deliberate measures are taken to prevent it.

While it’s true that repetitive manufacturing jobs are often seen as preferable to the harsh realities of pre-industrial life or scavenging in underdeveloped regions, we must remember that in the 19th century, a significant portion of the workforce outside agriculture was engaged in such mind-numbing tasks. These workers, like consumers supporting more efficient enterprises, deserve our respect.

Smith’s foresight, however, fell short of predicting the economic dynamism that would arise in free societies, leading to a workforce increasingly engaged in roles requiring knowledge and creativity. Today, manufacturing constitutes less than 10% of employment in America—a trend mirrored in many wealthy nations—where machines handle the more monotonous tasks. We should be grateful for this advancement. Our governments ought to resist the economically misguided and morally questionable urge to stifle the growth of poorer nations striving to elevate their living standards. For context, consider that China’s GDP per capita is only about one-third of that of the U.S., while Vietnam’s is a mere 14%, according to the 2023 Maddison Project database.

Ultimately, we must grapple with crucial questions: Who should produce what, how, and where? Economic theory and history present us with two contrasting paths. The first suggests centralizing decision-making with authorities—be it tribal leaders, politicians, or bureaucrats. The second advocates for consumer sovereignty, free enterprise, competition, and laissez-faire principles, empowering individuals and voluntary associations (including corporations) to determine their production and trading terms.

******************************

Mindless manufacturing