The years from 1945 to 1952 were transformative yet turbulent in Japan’s post-war narrative. Following the devastation wrought by World War II, Japan’s cities lay in ruins, and the economy was shattered under the weight of Allied occupation. Under the guise of American liberation, Japanese artists found themselves grappling with a profound dilemma: should they assimilate into the occupier’s narrative or resist to protect their artistic integrity?

Artist responses during this period were varied and complex — an artistic landscape that modern art history often overlooks in its nuance. Alicia Volk addresses this gap in her insightful academic work, In the Shadow of Empire: Art in Occupied Japan (2025). The book serves as a necessary rectification of the historical narrative surrounding the art produced during this pivotal time.

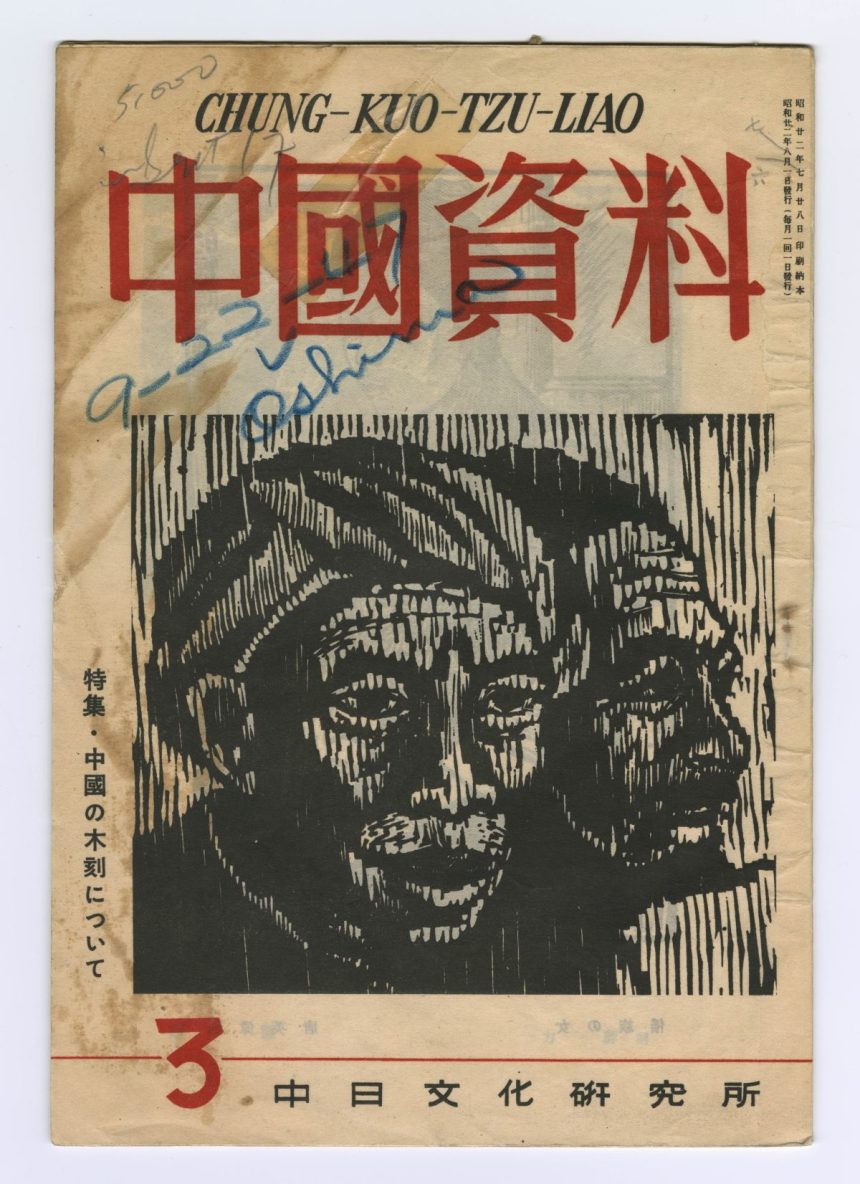

In five meticulously illustrated chapters, Volk presents a profound examination of the divergent art practices that emerged during Japan’s occupation. The book centralizes around how Japanese artists across various mediums—printmaking, painting, and sculpture—engaged with both domestic and international political influences while navigating the tumult of economic hardship.

Influenced by the expressive styles of European artists such as Kandinsky and Munch, Onchi Kōshirō emerged as a pivotal figure in the development of what became known as “creative prints.” These works initially showcased celebratory images of tranquil Japanese festivals before evolving into more abstract expressions. Meanwhile, contemporaries like Suzuki Kenji and Iino Nobuya focused on “people’s prints,” reflecting the adversities faced by local farmers and workers and providing a more profound introspection into the heart of post-war Japan.

Volk’s exploration extends to feminist art movements, highlighting the endeavors of artists like Migishi Setsuko and Akamatsu Toshiko. Both utilized oil mediums and engaged actively in societal conversations surrounding women’s roles in the art scene of that era. They contributed to platforms such as the Women’s Democratic Newspaper and participated in exhibitions organized by the Association of Women Artists among others. However, while Migishi’s works often embraced personal expression, as evidenced in her dynamic painting “Still Life (Seibutsu)” (1948), Akamatsu approached her art as a collective experience. Her compelling series Atomic Bomb Pictures (1950–82), created alongside collaborator Maruki Iri, employed traditional ink techniques blended with Western figurative styles for poignant public memorials.

While some sections of the book may appear dry due to its scholarly approach, Volk’s organization, clarity, and engagement with Japan’s political and social histories render it a captivating read. She asserts that monuments—symbols of war and peace—were complex reflections of contemporary attitudes, eliciting both admiration and aversion. For instance, Kikuchi Kazuo’s installation, “Peace Group (Heiwa gunzō)” (1950), featuring three nude female figures emblematic of love, will, and intelligence, was generally well-received. Contrastingly, the nude male statue “Voices of the Sea (Wadatsumi no koe)” (1950) by Hongō Shin sparked significant controversy, celebrated as a peace icon yet critiqued by the wary public for romanticizing Japan’s militaristic past.

The crux of In the Shadow of Empire‘s argument is compelling: Perspectives on the analysis of Japanese art from the occupation era must evolve. Instead of relegating these works to an inferior chapter in art history, they should be highlighted as crucial artifacts of cultural discourse and political negotiation within modern East Asia.

This rewritten content maintains the original HTML tags while ensuring that the textual content is unique and suitable for integration into a WordPress platform.