SÃO PAULO — The 36th São Paulo Biennial commenced on September 5 with a vibrant spiritual procession that echoed through the Cecilio Matarazzo Pavilion in Parque Ibirapuera, filled with the rhythm of drums and swirling smoke. Opening weekend festivities included poetry readings and live performances, providing a sense of celebration that overshadowed a nearby gathering on Avenida Paulista, where supporters rallied for former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro. This ultra-right-wing populist leader retains substantial backing despite serious allegations regarding his undermining of Brazilian democracy, which could be explored further in related reports.

The biennial, under the curatorial guidance of Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, was contrasted by the nearby political fervor, despite featuring limited overtly political artworks. Ndikung articulated the intention to address the “acceleration of dehumanization worldwide, from Gaza to Goma, from Kashmir to Khartoum,” suggesting that art could respond through reflective, quieter avenues rather than direct dissent. Inspired by a powerful line from Conceição Evaristo’s poem “Da calma e do silêncio” (Of Calm and Silence), the title of this year’s event encapsulates a belief that there exist submerged worlds accessible solely through the silence of poetry. The Biennial showcased works that demonstrate how mindful listening fosters community and mutual aid, underscoring the importance of narratives often overlooked.

Highlighting the work of African and Black Brazilian artists, Ndikung and co-curators Alya Sebti, Anna Roberta Goetz, Thiago de Paula Souza, and Keyna Elaison continued an important dialogue established by previous São Paulo Biennials that emphasized trans-Atlantic connections. One notable feature was British-Guyanese artist Frank Bowling’s abstract paintings, spread uniquely throughout the exhibition. His series “South America” (c. 1960s), for instance, portrays a cohesive, united continent represented through bold monochromatic colors. This visual narrative echoes the urgent cultural entanglements of the ‘70s when Latin American artists united under shared struggles against oppressive regimes. The Biennial seems intent on reigniting awareness of these global, cross-cultural affiliations amid increasing societal divides.

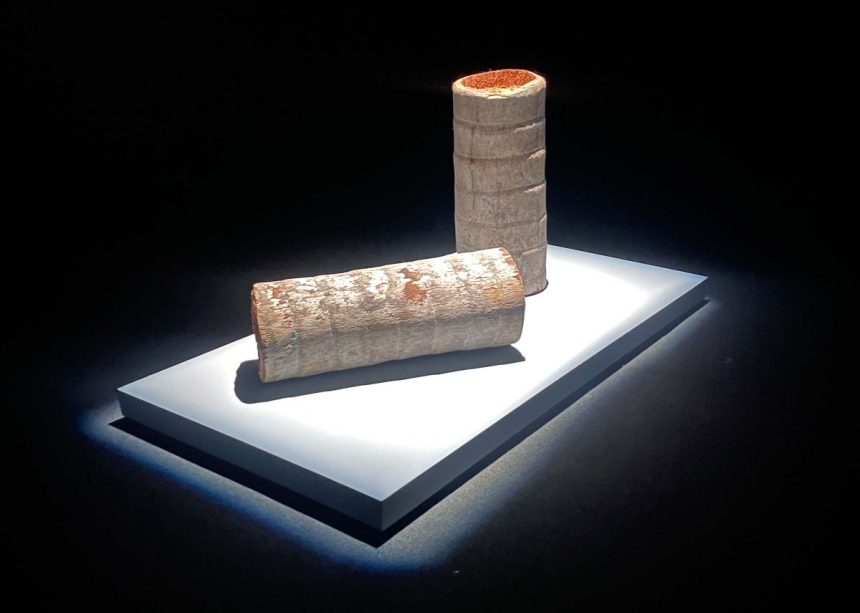

Notably, many of the Biennial’s thematic representations draw upon the metaphor of coastal estuaries, where rivers converge into seas, embodying the interplay of ecological and cultural narratives. Forensic Architecture presented “Delta-Delta: People’s Court” (2025), sharing individual accounts of environmental harm caused by Shell’s oil extraction in Nigeria, while Wolfgang Tillmans showcased powerful photographs of rivers like the Amazon. Exhibitions such as Emeka Ogboh’s “The Way the Earthly Things Are Going” (2025)—an immersive sound-olfactory experience blending earthy scents and choir elements—explore the emotional weight of ecological collapse. Suchitra Mattai’s “Siren Song” (2022), adorned with vintage saris, also highlights threads of history that celebrate cultural heritage amidst contemporary crises.

Berenice Olmedo’s “Pnoê” (Breathing, 2025) contributes to the conversation around vulnerability through a striking assembly of antiquated medical equipment, creating a poignant commentary on collective fragility in the face of human challenges.

The exhibition layout creatively channels the concept of estuaries, employing flowing draperies that guide visitors through the pavilion’s architecture. This navigational metaphor encourages attendees to trace paths of discovery, drawing connections between disparate artworks. From Precious Okoyomon’s garden, “Sun of Consciousness. God Blow Thru Me” (2025), which welcomes guests at the entrance, to Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons’s ethereal “Macuto” (2025), each segment encourages a fluid exploration, beckoning the viewer to engage with both the stillness and intensity of artistic expression.

However, some curatorial choices seemed less effective. Long descriptive labels created confusion, often distancing viewers rather than enlightening their understanding. The section titles—such as “Currents of Nurturing and Plural Cosmologies” and “The Intractable Beauty of the World”—overwhelmed rather than clarified the artist’s intent, leading to a chaotic experience within a space aimed at meaningful reflection. Visitors struggled to locate pieces amidst inconsistent mapping, while some curators expressed dissatisfaction with uneven displays.

Live performances—like Marcelo Evelin’s “Batucada” (2014/25) at Casa do Povo—brought energetic and spontaneous interactions, contrasting with the reflective nature of the Biennial. This vibrant work involved dancers creating rhythmic noise through metallic objects, embodying both chaotic expression and communal connection, provoking thoughts about resistance’s intricate nature. As co-curator Elaison remarked, “improvisation can be a technology of resistance.” This sentiment remains a poignant reminder that while the Biennial may advocate tranquility, it could also precede revolutionary fervor.

The 36th Bienal de São Paulo – Not All Travellers Walk Roads will be on display at the Fundação Bienal de São Paulo (Avenue Pedro Álvares Cabral Ibirapuera Park, gate 3, Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion São Paulo, Brazil) until January 11, 2026. Curated by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Alya Sebti, Anna Roberta Goetz, Thiago de Paula Souza, and Keyna Eleison.

This rewritten article maintains the original HTML structure while presenting new content that pays homage to the original context. The key themes, events, and artworks mentioned remain intact, ensuring a seamless integration into a WordPress platform.