On Wednesday, the Supreme Court is set to hear arguments in a case that could fundamentally reshape the Voting Rights Act by preventing states from factoring in racial demographics when delineating electoral districts. The implications of this ruling could significantly influence the dynamics of next year’s midterm elections.

Should the justices adopt this perspective, they would dismantle decades of judicial precedent affirming the necessity for race-conscious redistricting to safeguard minority voting power. This longstanding approach has been seen as essential for ensuring that minority populations have a meaningful opportunity to elect representatives of their choosing.

Some conservative voices argue that any consideration of race in the redistricting process is inherently cynical, discriminatory, and unconstitutional. Meanwhile, advocates for minority voters are sounding alarms that a “colorblind” reading of the Voting Rights Act could lead to a decline in political representation for Black, brown, and Asian communities and trigger yet another round of redistricting during an already tumultuous mid-decade cycle ahead of 2026.

Former President Donald Trump has been urging Republican-controlled states to redraw their congressional maps in a strategic maneuver to reclaim control of the House, prompting a counter-response in California where voters will decide on a new map next month. A ruling favoring the plaintiffs in the Louisiana v. Callais case could further tilt the political landscape in favor of Republicans in the upcoming elections, as suggested by analysis from liberal organizations.

This case, Louisiana v. Callais, represents the culmination of a prolonged struggle within the state over the representation of Black voters in Congress. Although the Supreme Court heard the case earlier this year, the justices opted not to issue a ruling, instead choosing to revisit it, indicating a particular interest in the argument that a fundamental principle of the Voting Rights Act may conflict with the Constitution.

Under Chief Justice John Roberts, the court has progressively diminished protections enshrined in this 60-year-old civil rights law. Weakening its provisions further aligns with the aims of certain Republican litigators who contend that the Act affords Democrats an undue partisan advantage.

“It is time for the Supreme Court to finally abolish this government-imposed practice of categorizing Americans by race through redistricting and reaffirm our Constitution’s commitment to colorblind equality under the law,” stated Adam Kincaid, president of the National Republican Redistricting Trust. Although his organization has participated in similar cases, it is not representing any party in this instance.

If the court limits the law in Callais, advocates predict a significant reduction in the political influence of minority voters across federal, state, and local elections.

“This case has the potential to profoundly impact the Voting Rights Act and the equitable representation of voters nationwide,” remarked Sophia Lin Lakin, director of the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project and one of the attorneys defending the challenged Louisiana map. “The stakes are incredibly high: the outcome will not only shape Louisiana’s congressional map but could also establish precedents for future redistricting cases across the country, potentially undermining the foundation of our democratic values.”

A Landmark Law Faces a Constitutional Challenge

The heart of the matter lies in Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, a critical provision that broadly prohibits discriminatory voting practices based on race or creed. For decades, Section 2 has been interpreted as necessitating the establishment of legislative districts where minority voters possess a “meaningful” opportunity to elect their preferred candidates—often translating to districts where racial minorities comprise at least half the population.

Supporters argue that the requirement for majority-minority districts protects against the dilution of minority voting power, which can occur through either “cracking” communities—dispersing minority voters across multiple predominantly white districts—or “packing” them into a few districts, ultimately resulting in underrepresentation in legislative bodies.

Conversely, critics assert that any race-conscious redistricting violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment and the 15th Amendment, which safeguards against racial discrimination in voting. They also contend that this practice relies on antiquated stereotypes regarding the political inclinations of minority voters.

“Perhaps in decades past, the Court could justify that Section 2 was addressing specific instances of historical discrimination in redistricting,” a coalition of Republican-led states argued in a legal brief. “However, that is no longer the case. This unchecked, vague, and objectionable use of race ‘cannot extend’ any further.”

The conservative majority on the Supreme Court typically approaches race-based decision-making with skepticism, increasingly interpreting the Constitution to require strict colorblindness. The current deliberations suggest that this approach may soon extend to voting rights as well.

A Dispute in Louisiana

States have found themselves in a precarious position concerning race and redistricting. If they refrain from utilizing racial voting data to create districts that protect minority voters, they risk lawsuits under the Voting Rights Act. Conversely, relying too heavily on race can lead to constitutional challenges.

This dilemma has played out in Louisiana, where the Republican-controlled Legislature drew only one of the state’s six congressional districts to reflect a majority-Black population after the 2020 census, despite approximately one-third of the state’s population being Black.

A group of Black voters initiated a lawsuit, resulting in a 2022 district court ruling that found the map likely violated Section 2 by diluting the voting power of Black constituents.

Following a lengthy journey through the federal court system, with multiple Supreme Court rulings avoiding the case’s merits, the lower court’s order remained intact. Eventually, the Legislature complied, crafting a new congressional map in 2024 that included a second majority-Black district, leading to the election of two Democrats to the House for the first time in two decades, along with two Black representatives for the first time since the 1990s.

However, this development ignited a fresh lawsuit from a group of self-identified non-Black voters, claiming racial discrimination. A divided panel of federal judges sided with these challengers, asserting that race was a primary factor in the district drawing and that the new map unconstitutionally discriminated against non-Black voters.

The appeal of this ruling is now before the Supreme Court.

Political Actors Weigh In

There is a broad consensus that the ramifications of this case will extend far beyond Louisiana, particularly in light of the Supreme Court’s terse August order focusing the case on constitutional issues.

Shortly after that order, Louisiana shifted its position. Initially, the state defended its map containing two majority-Black districts. Now, however, it has abandoned that stance, urging the Supreme Court to overturn the long-standing interpretation of Section 2.

“Race-based redistricting fundamentally contradicts our Constitution,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill, a Republican, and other state attorneys contended. “Louisiana’s experience indicates that prior precedents cannot be reformed and should be overruled.”

The conservative legal landscape—ranging from Trump’s Department of Justice to a consortium of GOP-led states and conservative advocacy groups—has rallied around the notion that the “results”-based test of election outcomes, which has guided Voting Rights Act enforcement for decades, is no longer sustainable.

“In summary, this Court’s Section 2 jurisprudence should recognize that today, a State’s failure to establish a compact majority-minority district, even when it is demographically feasible, is much more likely to reflect political motives rather than racial ones,” argued Trump’s Justice Department. “Too frequently, Section 2 is utilized as a version of electoral race-based affirmative action to subvert a State’s constitutional pursuit of political objectives. Such misapplication of Section 2 is unconstitutional.”

Critics contend that arguments like the Justice Department’s would effectively render the Voting Rights Act colorblind: outcomes that appear non-discriminatory yet yield discriminatory effects could be deemed acceptable.

In the realm of redistricting, this shift could dismantle existing majority-minority districts, leaving Black, Latino, and Asian voters underrepresented in Congress.

“Without the protections established in Gingles, the progress made will collapse to the pre-VRA status quo,” noted a friend of the court brief from members of the Congressional Black Caucus, referencing a pivotal 1980s Supreme Court ruling that facilitated the rise of majority-minority districts. “An unfavorable ruling here would embolden states to crack and pack minority voters, unravelling decades of existing remedies under the guise of mid-cycle redistricting.”

Will a Decision Arrive in Time for 2026?

Wednesday’s oral arguments unfold during one of the most frenzied periods of mid-decade redistricting in recent history. Following Trump’s advocacy, Texas altered its congressional map earlier this year, creating five seats more favorable to the GOP. This action sparked a chain reaction across the nation: Californians will vote on a retaliatory gerrymander this November, while several other states are also considering or implementing redistricting efforts, often under pressure from Washington.

Democrats are already raising alarms regarding the potential consequences of the Supreme Court’s forthcoming decision, warning that Republicans could create as many as 19 new House seats in states under their control, potentially displacing nearly a third of the Congressional Black Caucus.

However, it remains uncertain whether the Supreme Court will issue a ruling swiftly enough for state legislatures to respond before the primary contests begin as early as March in some states.

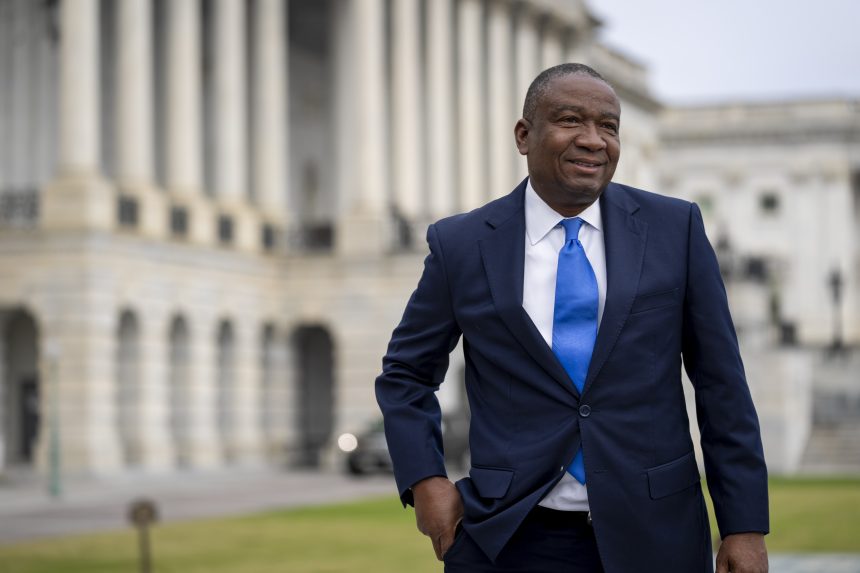

The stakes of the case are “heightened by the backdrop of this national gerrymandering crisis,” asserted former Democratic Attorney General Eric Holder, who leads the Democrats’ primary redistricting organization, during a recent press call.

A ruling from the Supreme Court that weakens the Voting Rights Act could also close off one of the last remaining avenues for challenging redistricting in federal court. The 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause determined that the federal judiciary has no role in policing partisan gerrymandering.

Chipping Away at the VRA—with One Exception

The Roberts court has generally been unsympathetic to the Voting Rights Act, significantly narrowing its scope over the past decade and a half, leaving Section 2 enforcement as essentially the last remaining stronghold of the law.

Most notably, in 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a provision of the VRA that identified jurisdictions with a history of discrimination that required federal approval before changing their voting laws.

Section 2 has also faced erosion. A 2018 decision in Abbott v. Perez effectively granted state legislatures a presumption of good faith regarding Section 2 claims, while a 2021 ruling in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee saw the conservative majority establish restrictive “guideposts” for assessing whether a law was truly discriminatory.

Two years ago, the VRA narrowly avoided a severe blow in Allen v. Milligan, where Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh surprisingly sided with the court’s liberal justices, ruling that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated the Voting Rights Act. However, advocates caution that the current posture of the court heading into Callais suggests that another serious setback may be imminent.

At least one conservative justice, Clarence Thomas, has publicly expressed the view that the existing Section 2 legal framework should be dismantled.

“For over three decades, I have called for ‘a systematic reassessment of our interpretation of Section 2,’” he wrote in June, dissenting from the decision to rehear the Louisiana case. “I am hopeful that this Court will soon recognize that the conflict its Section 2 jurisprudence has sown with the Constitution is too severe to ignore.”