Recent research indicates that even minimal alcohol consumption may significantly elevate the risk of developing dementia. This conclusion stems from the largest comprehensive observational and genetic investigation into the effects of alcohol on cognitive health conducted to date.

These findings challenge earlier studies that suggested light to moderate drinking could serve as a protective factor against cognitive decline. The international research team now advocates for complete abstinence from alcohol as the most effective strategy for reducing dementia risk, highlighting a direct correlation between greater alcohol intake and heightened likelihood of experiencing various forms of dementia.

“Our findings indicate a harmful impact of all varieties of alcohol consumption on dementia risk, demonstrating no support for the previously suggested protective effects of moderate drinking,” the researchers stated in their published paper.

Related: US Surgeon General Warns There Is No Safe Level of Alcohol Consumption

The study involved analyzing data from 559,559 participants in the UK and US, aged between 56 and 72 at the commencement of the research. Participants completed questionnaires regarding their drinking patterns, with their health monitored for up to 15 years following the initial data collection.

The first part of the research yielded a classic U-shaped graph, revealing that both non-drinkers and those consuming high amounts of alcohol exhibited the highest dementia risk. This pattern aligns with the twisting relationship proposed by the researchers.

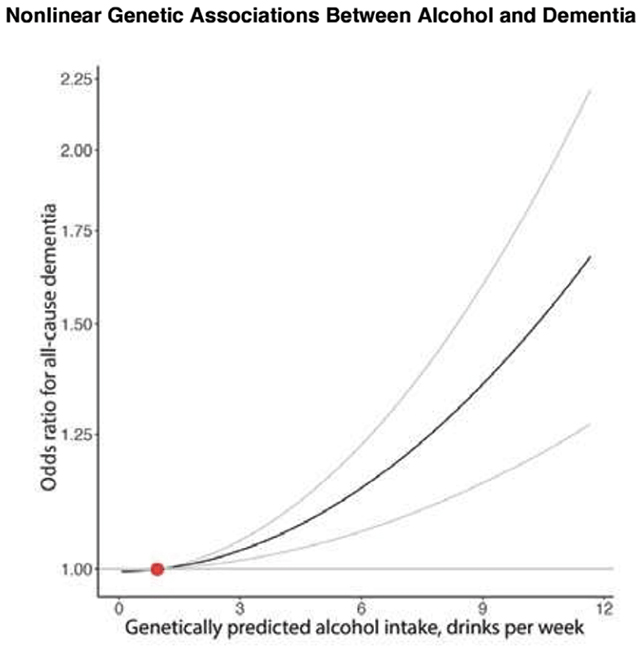

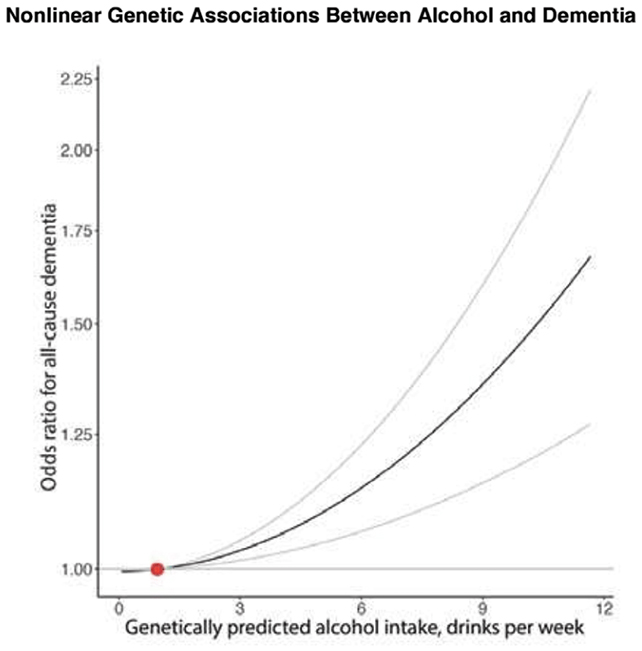

To bolster their findings, the researchers also scrutinized genetic records from 2.4 million individuals, employing Mendelian randomization to evaluate the relationship between drinking habits and dementia risk. This methodology leverages a genetic propensity for alcohol consumption rather than self-reported drinking behaviors, thus controlling for extraneous variables like lifestyle choices and socioeconomic status.

In this segment of the analysis, the U-shaped risk association disappeared. Instead, it was evident that higher predicted alcohol consumption correlated directly with increased dementia risk, indicating that even occasional drinking did not mitigate this danger.

“If we could reduce the prevalence of alcohol use disorder by half, we could potentially decrease dementia cases by up to 16 percent, emphasizing alcohol reduction as a viable route in dementia prevention strategies,” the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the researchers also acknowledged significant limitations. In the initial study phase, participant-reported drinking habits were utilized, which can often lead to discrepancies. Furthermore, while Mendelian randomization is a valuable analytical tool, it is dependent on correlating genetic data with tendencies rather than providing direct records of alcohol consumption.

Despite these challenges, the extensive nature of the study, combined with numerous prior studies, reinforces the notion that increased alcohol intake correlates with higher risks of cognitive decline and dementia as one ages.

“Neither phase of the study can definitively establish alcohol use as a direct cause of dementia,” stated neuroscientist Tara Spires-Jones from the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the research. “However, this contributes to a growing body of evidence linking alcohol consumption with dementia risk, and fundamental neuroscience research has highlighted alcohol’s neurotoxic effects on brain neurons.”

This pivotal research has been published in BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine.