A striking clue was discovered on the knees of a bee.

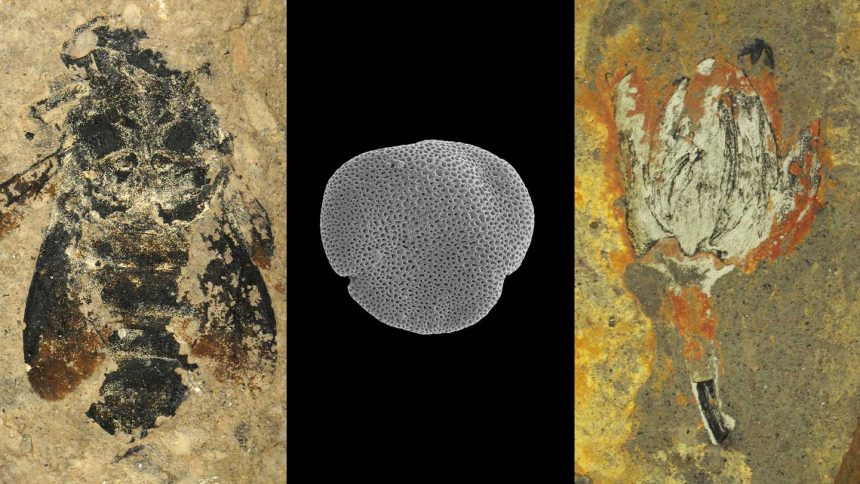

An examination of 127 ancient flower specimens, flower buds, and bees from central Germany identified pollen grains that distinctly matched ancient flowers with their pollinators. These fossils are approximately 24 million years old. Although there is evidence of insects covered in pollen from earlier periods, this finding represents the earliest documented case of a direct pollination relationship between species, as reported in the September 22 issue of New Phytologist.

“The presence of pollen on a fossil bee merely indicates that the insect visited flowers,” explains Constanza Peña-Kairath, an expert in ancient insect pollination previously at the University of Barcelona and not part of this study. She notes that the new research offers “a vital and remarkable piece of evidence” demonstrating a clear connection between a pollinator and its floral counterpart.

The fossils were discovered at an ancient crater lake in Enspel, situated between Düsseldorf and Frankfurt. In prehistoric times, the lake’s shoreline was surrounded by lush vegetation, providing a habitat for thriving bee populations. Occasionally, bees and flowers would end up in the lake, where they became enveloped by sediments, leading to their fossilization.

“Insects frequently tumble into water bodies and perish,” notes Christian Geier, a paleobotanist at the University of Vienna. “In the case of the fossilized bumblebees, they avoided being consumed by fish and sank to the lakebed instead.”

Geier and his team identified a novel species of linden tree, Tilia magnasepala, along with two new bumblebee species: Bombus messegus and B. palaeocrater. According to Geier, these findings represent the oldest bumblebee fossils documented in Europe.

Both the identified flowers and bees were saturated with pollen, enabling researchers to piece together the fossils like a jigsaw puzzle.

The team extracted pollen grains from various fossils, employing a scanning electron microscope to analyze the pollen’s intricate structure. The pollen found within the flowers corresponded perfectly with that on the new bumblebee species. Moreover, the bees displayed pollen on the undersides of their bodies, encompassing their legs, mouthparts, and abdomens, illustrating that they collected pollen upon landing on the cupped flowers of the linden trees.

Evidence of insects transporting pollen from nonflowering plants dates back at least 280 million years, predating an evolutionary explosion of flowering plants around 130 million years ago. The subsequent proliferation of flowering plants—making up around 90 percent of present-day flora—has been partially attributed to their pollinators, according to previous studies.

Currently, linden trees continue to rely on bumblebees for their pollination, establishing this as the longest known “direct evidence of a bee-flower interaction that persists today in Europe,” asserts Friðgeir Grímsson, another paleobotanist at the University of Vienna. The ability to trace a longstanding bond between a plant and its pollinator back 24 million years “highlights the significance of this discovery.”