The champions of anti-trade sentiment have reclaimed the political stage, once again vowing to resurrect those elusive “good-paying jobs” that America, they claim, has been robbed of over the years by “unfair” foreign competition. Tariffs, of course, are the favored weapon of these protectionists, a sentiment echoed by none other than President Trump, who has dubbed tariffs as “the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” In a recent proclamation, he made it clear that tariffs are central to his economic strategy. Howard Lutnick, Trump’s Commerce Secretary and a key economic advisor, reinforced this notion in a recent interview, emphasizing that the aim of these tariffs is to reignite manufacturing jobs in the United States:

“…under Donald Trump union labor is going to double because those factories are going to come back and those workers are going to get great jobs and we are going to have a different America, one that produces and manufactures. And if I need to use tariffs—this is the president talking—if I need to use tariffs to bring that manufacturing home, we’re going to do it.”

However, the chatter surrounding tariffs is breeding uncertainty and anxiety regarding the current and future performance of the U.S. economy. This is regrettable, as Trump’s broader economic agenda—which includes deregulation, tax cuts, access to affordable energy, and reducing government waste—might otherwise foster substantial economic growth. Instead, Trump’s tariffs are having an economically self-sabotaging effect reminiscent of a well-known football blunder, prompting economists to vocally criticize the erratic and counterproductive nature of his tariff strategies.

Numerous voices have already pointed out the economic fallout from tariffs. Here, I aim to delve deeper into the protectionists’ narrative about job losses and the promise of job recovery. Have we indeed lost manufacturing jobs? Absolutely. Is trade a contributing factor? Partially. But should we view this decline as catastrophic? Certainly not. Protectionists fall into the classic economic trap identified by Frederic Bastiat:

“There is only one difference between a bad economist and a good one: the bad economist confines himself to the visible effect; the good economist takes into account both the effect that can be seen and those effects that must be foreseen.”

Let’s take a step back from the job losses and evaluate the broader transformations within the U.S. economy amid this purported manufacturing downturn. Luckily, data provides a fairly clear picture of the job displacement caused by global trade. First, we must acknowledge the stark reality of manufacturing job losses: as illustrated in Figure 1, U.S. manufacturing employment plummeted by approximately 1.5 million positions from pre-Great Recession levels in 2006 and has decreased by nearly 7 million, or 35%, since the peak in 1979.

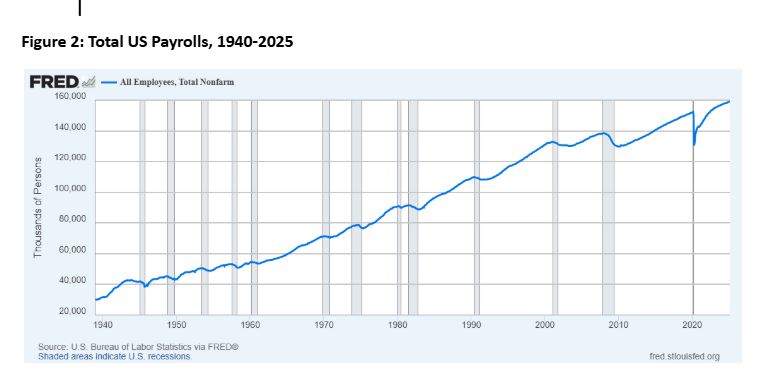

Indeed, the U.S. has been experiencing a steady decline in manufacturing jobs over decades, despite a slight recovery of around 1.5 million jobs since the nadir of the Great Recession. This overarching trend superficially bolsters the protectionist narrative regarding outsourcing and the so-called “de-industrialization” of America. However, manufacturing is merely a fragment of the vast U.S. economy. What happens when we consider employment across the entire economic landscape? It’s essential to recognize that total employment figures fluctuate with the business cycle. For example, the U.S. saw a staggering loss of 22 million jobs during the early 2020 COVID shutdowns, yet these losses were entirely recovered within two years, and since mid-2022, job growth has been consistently on the rise. The latest data reveals that payroll employment reached a new peak of 159 million as indicated by the February 2025 jobs report. The salient point here is the persistent, long-term upward trajectory of total employment, as depicted in Figure 2.

Not only is job growth evident, but it has also surpassed population growth—meaning that the increase in available jobs has consistently outpaced the rise in the number of people seeking employment for most of the last 40 years, as illustrated in Figure 3.

In my upcoming analysis, I will tackle the pressing question: “Does the increase in employment translate into positive economic outcomes?”

Tyler Watts is a professor of economics and management at Ferris State University.