For students delving into economics, particularly public choice theory, the expectation is clear: politicians are likely to stretch the truth—and in contemporary America, they are fulfilling this expectation with remarkable consistency. Politicians, after all, are just people. And like anyone else, they may feel tempted to mislead when it seems beneficial to their interests. Here, I define lying as the deliberate act of stating something one knows to be false. A softer variant might involve making statements one suspects could be easily disproven with minimal effort. My definition excludes so-called “white lies” justified by compassion, such as withholding the full truth from a terminally ill child, or lies told out of self-preservation, like those made to a thief or kidnapper. The economics of lying investigates the motivations behind dishonesty and its broader social ramifications.

There are compelling economic and moral arguments for an individual to refrain from lying. A significant moral rationale is rooted in the idea that a free society thrives on an ethic of reciprocity—essentially, treating others as equals who are likely to reciprocate honesty. You don’t deceive those who are honest with you. For an in-depth exploration of this concept, see James Buchanan’s insightful work, Why I, Too, Am Not a Conservative.

This moral argument intersects with economic reasoning, prompting consideration of the institutions that foster a spontaneous social order capable of maximizing individual opportunities. In a society characterized by freedom, people are less inclined to feel that others are always out to deceive them. Honesty and personal integrity—closely tied to truth-telling—cultivate trust and diminish the transaction costs that typically accompany social interactions. Conversely, in a collectivist framework, individuals are incentivized to exploit free “public goods” before they are depleted by others. Here, the self-interest of some individuals undermines the self-interest of others. Ultimately, one may lie simply because a culture of dishonesty prevails. (For further reading on this, refer to my post “Self-Interest and Capitalism Are Not Synonymous,” dated August 22, 2019; and for insights on collective choices leading to free-rider problems, see Anthony de Jasay’s Social Contract, Free Ride.)

The fundamental economic rationale for avoiding dishonesty—and cultivating a habit of truthfulness—is that a reputation for integrity tends to yield greater overall benefits than costs, particularly in a freer society. At least for those not “on the spectrum,” it’s challenging to earn trust while being known as a liar.

Moreover, a persistent liar risks devolving into incoherence or farce. Examples abound, from sensational claims about Haitians consuming pets to more recent political blunders, such as Guy Chazan’s article titled “‘Almost Comical’: The Trump Team’s First National Security Crisis” published in the Financial Times on March 28, 2025, and “The Cover-Up Is Worse Than the Group Chat,” which appeared in The Economist on March 27, 2025.

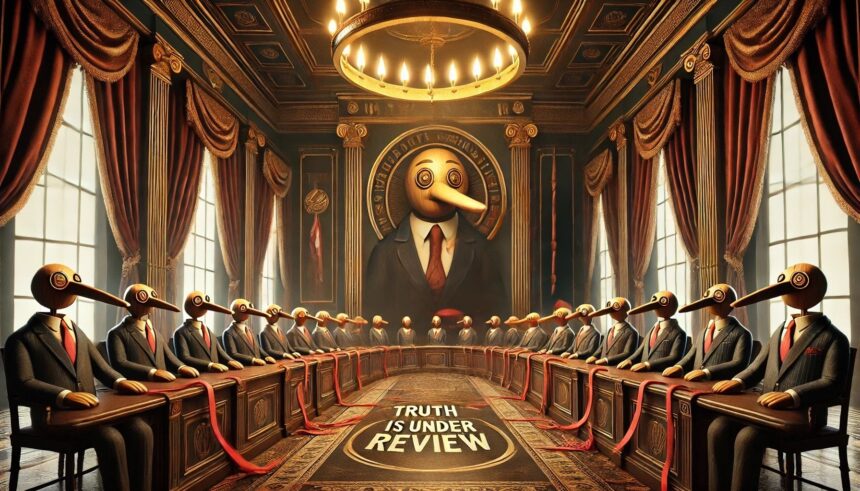

Several factors contribute to the diminished incentives for truth-telling among politicians. The more fervently a politician advocates for a policy, the less accountability he faces for the consequences, especially among rationally ignorant voters. From his elevated perch, a politician can easily deflect blame onto judges, foreign adversaries, the media, or even the so-called “enemies of the people,” all while justifying an expansion of his own power in direct correlation to policy failures. This cycle of dishonesty breeds a culture where if one politician is shamelessly dishonest, his competitors feel emboldened to follow suit. As the leader lies with impunity, subordinates and sycophants find themselves pressured to deceive as well, often as a matter of expectation or directive. This selection process tends to elevate individuals who are either predisposed to lie or comfortable with it into positions of power. Such dynamics help elucidate why, in a politicized society, the least virtuous often rise to the top, perpetuating a cycle of corruption (for further exploration, see my post “What Is Kakistocracy”). Once a regime of this nature becomes entrenched, reversing it is exceedingly difficult; today’s Russia serves as a poignant example.

******************************

A Cabinet meeting in Syldavia, by DALL-E under the influence of your humble blogger (the red tape is an addendum by the chatbot)