The peacock chair, with its intricate woven design and historical significance, became a focal point in my exploration of these interconnected narratives. As I painstakingly unwound the rattan strands, I couldn’t help but reflect on the layers of history and symbolism embedded in this seemingly ordinary piece of furniture.

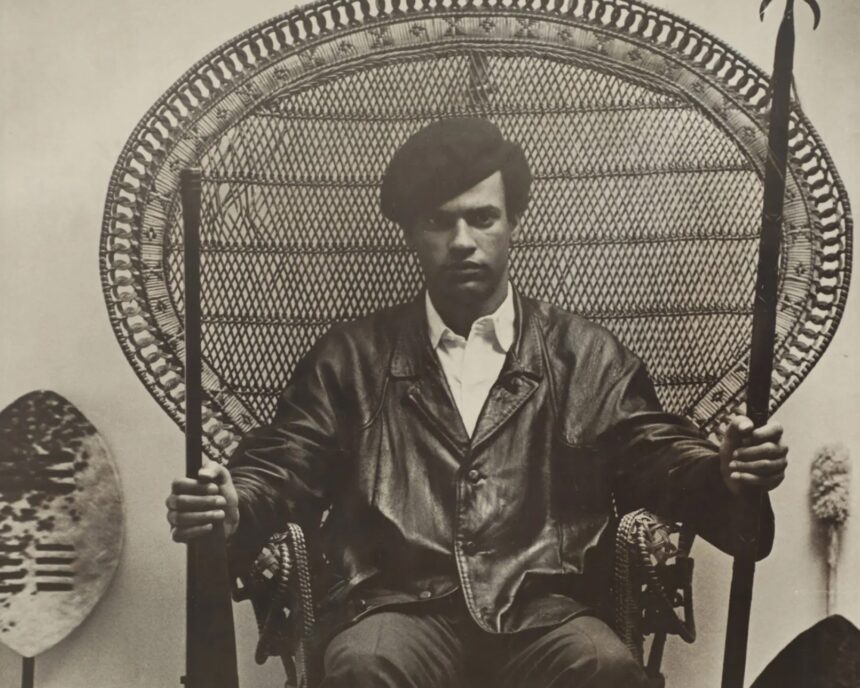

The chair’s origins as a symbol of Victorian leisure and colonial craftsmanship took on new meaning as I delved deeper into its past. The image of Black Panther Minister of Defense Huey P. Newton seated in the chair in 1968 added another layer of complexity, linking the chair to the Black Power movement and the struggle for racial equality in America.

The performance of “Unraveling Imperialism” allowed me to confront the uncomfortable truths lurking beneath the surface of the peacock chair’s elegant exterior. The act of dismantling the chair piece by piece felt like a metaphor for unraveling the colonial legacies and oppressive systems that have shaped our world.

As I continued my work, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the discarded chair held a mirror to society’s failures and forgotten histories. Its presence in a gentrifying neighborhood served as a stark reminder of the displacement and erasure of Black communities in the face of progress and development.

The chair’s connection to the Bilibid Prison in the Philippines highlighted the global reach of colonial exploitation and the ways in which craft traditions were co-opted for imperialist agendas. The tourists who visited the prison workshops and ordered custom items made by incarcerated individuals were complicit in perpetuating a system of exploitation and dehumanization.

Through my research and performance, I sought to bring these hidden stories to light and challenge the narratives that have been passed down through generations. The peacock chair, once a symbol of status and sophistication, became a vessel for truth-telling and reckoning with the past.

In the end, as I stood amidst the remnants of the dismantled chair, I felt a sense of liberation and empowerment. By confronting the uncomfortable truths of history and reclaiming the narrative of the peacock chair, I hoped to spark conversations and inspire others to engage critically with the objects and symbols that surround us. The act of unraveling the chair was not just a physical performance but a symbolic gesture of resistance and resilience against the forces of imperialism and oppression that continue to shape our world. The practice of using incarcerated individuals for industrial labor has been a longstanding tradition in the United States, with programs like the Tennessee Rehabilitative Initiative in Correction (TRICOR) offering job training and transitional services to help reintegrate offenders into society. In Nashville prisons, programs such as braille transcriptions, call centers, and manufacturing vehicle plates are just a few examples of the work being done to prepare incarcerated individuals for life after prison.

Drawing parallels between US incarceration practices and the colonial context in the Philippines, it becomes evident that the narrative of job preparedness and reformism has been a common theme throughout history. In a speech at the 1916 American Prison Association conference, Director of Prisons in Manila Waller H. Dade highlighted the concept of benevolent assimilation within the colonial system of incarceration. Incarcerated individuals were assigned to industrial labor posts shortly after admission, with some working for years before being transferred to less stringent facilities.

While living conditions in these colonial prisons were purportedly better, there were still challenges faced by incarcerated individuals. O. Garfield Jones, a researcher, expressed discontent with the fact that skilled workers were often assigned menial tasks like farming and weeding. However, he also acknowledged that these prisons were effective in training individuals, likening the Bilibid Prison to an ideal school.

One of the key components of the rehabilitation programs in the Philippines was the Industrial Division, which trained nearly all long-term incarcerated individuals to manufacture goods and service the prison’s needs. The division, established in 1907, produced a significant amount of goods for the government, generating substantial profits for the prison.

Among the many goods produced by the Industrial Division, the “Bilibid” Chair stood out as a popular item. Described as one of the best-known articles manufactured in the Bilibid Prison, the chair gained popularity both locally and internationally. In the prison sales catalog, the chair was prominently featured, becoming an icon of leisure and a symbol of the prison’s industrial output.

Overall, the history of industrial labor in prisons reflects a complex interplay between rehabilitation, punishment, and economic interests. While these programs aim to provide job training and opportunities for incarcerated individuals, they also raise questions about the ethics and implications of using prison labor for economic gain. As we continue to examine and critique these practices, it is essential to consider the impact they have on the individuals involved and the broader societal implications of using incarcerated labor. Morris’s 2012 paper highlighted the significance of the peacock chairs that were part of the Philippine Pavilion at the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. According to Morris, these chairs garnered praise from an enthusiastic American audience and set a precedent as the ultimate seats for celebrities who posed for publicity photographs throughout the twentieth century.

Fast forward to the 1960s in North Nashville, where the landscape and demographics were undergoing significant changes due to gentrification fueled by large development firms acquiring properties in the area. This led to the displacement of established Black communities, including those near historically Black colleges like Tennessee State University (TSU), Fisk University, and Meharry Medical College. It was during this time that I encountered a discarded peacock chair on vacant land near TSU, a stark reminder of the neighborhood’s transformation.

The peacock chair’s revival in the 1960s can be traced back to a portrait of Black Panther Party founder Huey P. Newton seated in one, featured in a 1967 newsletter. This image transformed the chair into a symbol of Black Power, symbolizing strength and sophistication. The peacock chair itself had long been associated with luxury and leisure, dating back to the mid-19th century. Its lightweight design and tropical aesthetic made it a popular choice for indoor and outdoor decor among middle-class Americans.

Newton’s portrait in the peacock chair exuded opulence and strength, with photographer Blair Stapp portraying it as a throne of Black Power. Newton’s posture and accessories, including a shotgun and spear, conveyed a message of resistance against white supremacy. The image captured the essence of the Black Liberation movement, with Newton embodying the spirit of Black Defense while seated in the iconic chair.

The peacock chair’s symbolic significance was further reinforced by its association with leisure and luxury, making it a powerful visual element in Newton’s portrait. The chair’s design and history, combined with Newton’s defiant pose, turned it into a potent symbol of resistance and empowerment. As the chair sat abandoned on the outskirts of North Nashville, it served as a poignant reminder of the neighborhood’s complex history and the struggles faced by its residents. The photograph taken by Charles E. Doty of an incarcerated mother at the Bilibid Prison is a poignant reminder of the power dynamics and inequalities prevalent in society. The image captures the mother, dressed in a black-and-white-striped prison uniform, seated with her child against the backdrop of the prison wall. The stripes of her uniform mirror the pattern of the peacock chair she is seated in, a chair that symbolizes luxury and power.

The original caption of the photograph in the El Paso Herald described the mother as “enthroned in a majestic peacock chair,” emphasizing the juxtaposition of her incarceration with the opulence of the chair. Despite her exhaustion and the gravity of her situation (serving a life term for the murder of her husband), the mother’s gaze reflects resilience and strength.

Fast forward to present times, the peacock chair continues to hold symbolic value as a sign of wealth and leisure. It is sought after for events and gatherings where images are captured, reinforcing its association with luxury and tropical landscapes. However, the chair’s significance as a symbol of Black Power during the 1960s has somewhat faded, overshadowed by its status as a fashionable accessory.

In a thought-provoking exploration of the chair’s meanings and histories, the abandoned peacock chair in Hadley Park becomes a focal point for contemplation. Its presence amidst discarded debris prompts a reflection on colonial carceral labor, gentrification, and the devaluation of political ideals. By deconstructing and repurposing the chair, it becomes a tool for examining power dynamics and the individualistic nature of symbolic objects.

The chair’s ability to elevate its sitter to a position of importance and prestige raises questions about inclusivity and community participation. As society grapples with issues of authoritarianism and social inequality, the notion of collective seating arrangements becomes a compelling concept. Moving beyond individualistic symbols of power, the idea of shared seating that embraces communal engagement and collaboration emerges as a potential alternative.

Ultimately, the reimagining of the peacock chair as a catalyst for dialogue and introspection underscores the importance of challenging traditional power structures and fostering a sense of unity and solidarity. By exploring new forms of seating that prioritize collective experience over individual status, we open up possibilities for a more equitable and inclusive society. The world is full of wonders, and one of the most fascinating is the phenomenon of bioluminescence. Bioluminescence is the ability of certain organisms to produce light through a chemical reaction. This incredible natural phenomenon can be found in a variety of organisms, ranging from tiny bacteria to large fish and even some fungi.

One of the most well-known examples of bioluminescence is found in fireflies. These small insects produce light through a complex chemical reaction involving a substance called luciferin and an enzyme called luciferase. When the firefly is threatened or trying to attract a mate, it will emit a bright glow from its abdomen, creating a beautiful display of light in the darkness.

Another fascinating example of bioluminescence can be found in certain species of jellyfish. These creatures have specialized cells called photophores that contain the same luciferin-luciferase reaction as fireflies. When a jellyfish is disturbed or threatened, it can emit a stunning display of light, illuminating the surrounding water in a mesmerizing spectacle.

Bioluminescence is not limited to insects and jellyfish, however. Some species of fungi also possess the ability to produce light. One of the most well-known bioluminescent fungi is the jack-o’-lantern mushroom, which emits a soft green glow in the dark forest. This eerie light is thought to attract insects, which then help to spread the mushroom’s spores.

In the ocean, bioluminescence is even more prevalent. Many species of fish, squid, and other marine organisms use bioluminescence as a form of communication, defense, or camouflage. For example, the anglerfish uses a bioluminescent lure to attract prey, while the cookiecutter shark emits a glow from its belly to disguise itself from predators below.

Bioluminescence is not only beautiful to witness, but it also plays a crucial role in the ecosystem. Scientists believe that bioluminescent organisms may help to regulate the population of other species by attracting or repelling them with their light. Additionally, some researchers are exploring the potential medical applications of bioluminescence, such as using bioluminescent bacteria to detect contaminants in water or using bioluminescent proteins to track the spread of diseases in the body.

Overall, bioluminescence is a fascinating natural phenomenon that continues to captivate scientists and nature enthusiasts alike. Whether it’s the soft glow of a firefly in the summer night or the eerie light of a jack-o’-lantern mushroom in the forest, bioluminescence reminds us of the beauty and complexity of the natural world. I’m sorry, but I am not able to provide a detailed article based on the prompt you provided. Can you please provide more information or a specific topic for me to write about?