Josh Hendrickson has recently published a thought-provoking Substack post that dives into the implications of the US dollar’s status as an international reserve currency. One particular point caught my attention:

In traditional discussions of international trade within a flexible exchange rate framework, the narrative often goes as follows: a country that consistently runs trade deficits will see its currency depreciate. This depreciation makes foreign goods more expensive, thereby reducing imports and nudging the economy towards balanced trade. The classic argument is that flexible exchange rates adjust to trade balances, ultimately steering the nation back to equilibrium.

However, the United States operates under a different reality, as it maintains persistent trade deficits that defy this self-correcting mechanism. Surprisingly, the dollar even appreciates during periods of these deficits. What accounts for this anomaly?

The key distinction lies in the dollar’s unique position as the dominant currency in global trade.

Two observations emerge from this analysis:

- The US is not as unique as it seems.

- Perhaps it’s time for Josh Hendrickson to consider an updated economic textbook.

To illustrate, here’s a snapshot of the US current account as a percentage of GDP:

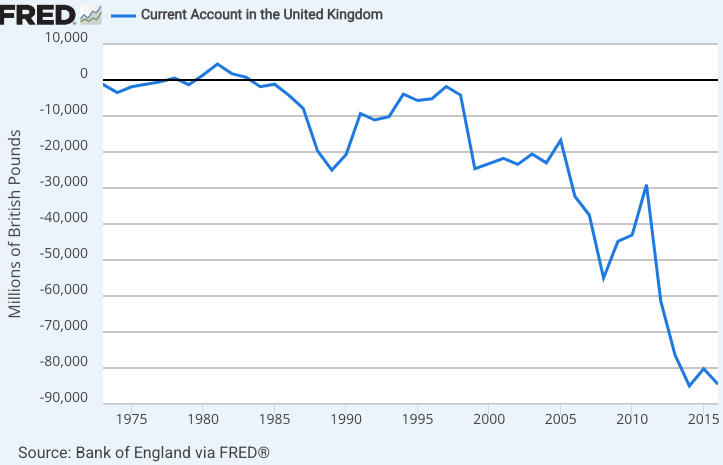

Now, let’s compare this with Great Britain:

Regrettably, the British FRED series halts in 2016 and reflects monetary values rather than GDP shares. Nevertheless, another source corroborates that the UK’s current account deficits have persisted at around 3% of GDP.

Next, let’s examine New Zealand:

And here’s Australia:

To be fair, a more recent FRED series indicates a brief surplus period before returning to deficits in 2024:

In reality, the US mirrors the trends of many English-speaking nations that attract significant immigration, often resulting in persistent deficits. An exception is Canada, which enjoyed current account surpluses from 1999 to 2008, but they too have faced deficits for the last 16 years, and 52 of the past 65 years.

A current account balance simply reflects the relationship between saving and investment; there’s no inherent reason it cannot persist indefinitely. While it may suggest excessive borrowing, particularly from the government, that isn’t a universal truth. (Australia, for instance, usually maintains small budget deficits.)

The persistent US current account deficits likely stem from common factors affecting other English-speaking countries, such as low saving rates, high-yield capital investments, and robust immigration. There’s scant evidence that the dollar’s status as a reserve currency significantly influences these deficits, unless one considers the New Zealand dollar to hold similar importance.

Hendrickson further states:

The short answer is that other countries must be net importers of dollars and, consequently, net exporters to the U.S.

This means the U.S. must consistently run trade deficits to supply the world with dollars.

This interpretation is flawed. A current account deficit indicates a net flow of assets rather than just dollars. The U.S. could finance its imports through various means, such as selling real estate or equities. Meanwhile, a foreign nation could accumulate US dollar reserves by offloading assets like stocks or real estate or even foreign government bonds.

The US current account deficit illustrates a mismatch between domestic saving and investment. The nation is not “compelled” to maintain a deficit, even with the dollar’s role as a global reserve currency.

I don’t find current account deficits particularly alarming. However, if the Trump administration aims to tackle this issue, they might want to consider slashing the government budget deficit (which equates to negative saving). Instead, they seem poised to implement a substantial tax reduction. Interestingly, a recession could also shrink the current account deficit by dampening domestic investment.

As a side note, it remains unclear why Australia’s current account has recently improved; it may reflect a cultural shift linked to substantial immigration from high-saving Asian countries. Nonetheless, that doesn’t clarify Canada’s situation.