China is currently grappling with a housing market collapse that rivals the infamous downturn experienced by the United States between 2006 and 2010. To grasp the implications of this crash, it’s essential first to examine the earlier U.S. scenario.

From January 2006 to April 2008, U.S. housing construction plummeted by over 50%. Remarkably, the economy managed to hold its ground, as other sectors adapted to absorb the fallout. Unemployment only crept up from 4.7% to 5.0%, maintaining a robust labor market.

However, in mid-2008, the Federal Reserve implemented one of the most stringent monetary policies in U.S. history, leading to a decline in nominal GDP (NGDP). Housing construction continued its descent, falling to approximately 70% below the peak reached in January 2006. More critically, other sectors also began to falter, causing unemployment to surge from 5% to 10%. This marked the onset of the worst recession since the Great Depression.

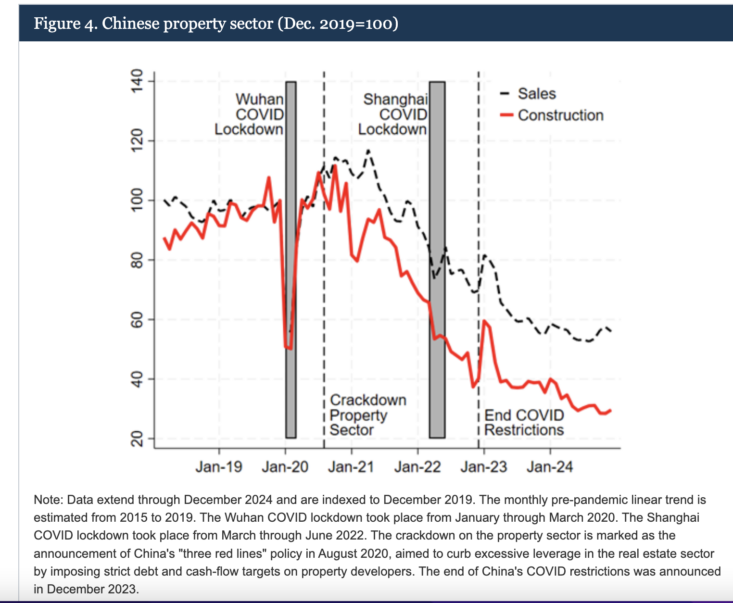

A captivating new paper by Federal Reserve economists William L. Barcelona, Danilo Cascaldi-Garcia, Jasper J. Hoek, and Eva Van Leemput reveals that China has encountered a similar slump in housing construction:

In many ways, the shock to China’s housing market is even more severe than that which hit the U.S. At its peak, the property sector constituted about 30% of China’s GDP—significantly higher than the U.S. housing boom ratio. Surprisingly, the authors found that Chinese GDP growth has remained relatively stable despite the severe downturn in such a critical economic sector:

While 5 percent growth is considerably slower than the 10 percent average growth rate China enjoyed from the 1980s to the early 2010s, it appears relatively favorable given the ongoing correction in the property market. Estimates have suggested that the real estate sector directly or indirectly accounted for as much as 30 percent of GDP, with official data indicating that real estate and construction activities contributed more than 1 percentage point to GDP growth (Rogoff and Yang, 2024). With the property market’s bubble bursting in recent years, this contribution has shifted from a boost to a drag on GDP growth.

3. China Activity Data

What accounts for this surprising resilience in growth, in light of the property sector’s troubles? Insights can be gleaned from various indicators illuminating different facets of the Chinese economy since the pandemic. Panel (a) of Figure 3 indicates that although industrial production faced severe disruptions during the initial lockdowns in Wuhan, it rebounded rapidly and has even surpassed its pre-pandemic growth trend.

This scenario mirrors early stages of the U.S. housing slump. The Fed managed to keep NGDP growing, allowing declines in residential construction to be balanced out by gains in manufacturing, exports, services, and commercial construction.

I’ve argued that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) has been overly restrictive in its monetary policy in recent years. Nevertheless, it has been more accommodative than the Fed was during the 2008-09 crisis, enabling Chinese NGDP to persist in its upward trajectory and the broader economy to keep moving forward.

Interestingly, while the Fed economists contributed to this analysis, they failed to highlight the stark contrast between the PBoC’s handling of the housing market crisis and the Fed’s mismanagement of the U.S. downturn. Vaidas Urba pointed me toward a recent tweet by Zach Mazlish discussing another relevant paper:

This paper, authored by Tomás E. Caravello, Alisdair McKay, and Christian K. Wolf, posits intriguing findings:

The primary conclusion is that, if there were no effective lower bound on nominal interest rates, a policy aimed at minimizing the output gap would have necessitated an aggressive rate cut to around -5 percent. Such an (unrealistic) reduction would have significantly narrowed the output gap, albeit at the cost of slightly higher inflation.

The findings are illustrated in Figure 9, which presents both realized (black) and hypothetical (blue) trajectories of output, inflation, and interest rates. The blue areas correspond to the posterior across all four models, with results being quite consistent among them. Our research illuminates the broader policy response during the Great Recession. Given the constraints on nominal interest rates, policymakers sought to compensate through alternative stimulative measures, particularly unconventional monetary policy and fiscal stimulus. If we interpret this analysis as a monetary policy objective, our counterfactual suggests that the unconventional response was inadequate—in nominal interest rate terms, an additional stimulus of roughly 500 basis points would have been necessary.

In a follow-up tweet, Mazlish anticipates one of my potential reactions (albeit I feel late 2007 was a bit premature—I’d posit June 2008 would have been a more appropriate time for the zero lower bound discussion):

A second point worth noting is that a more effective policy regime could have alleviated the severity of the demand shock in late 2008, thereby reducing the extent of monetary stimulus needed. For instance, a credible commitment to NGDP level targeting could have established stabilizing expectations for faster future NGDP growth following a brief downturn in mid-2008, thereby preventing the natural interest rate from plummeting as sharply. This isn’t merely my perspective; the advantages of level targeting have been substantiated in academic studies by figures like Ben Bernanke and Michael Woodford, building upon the theoretical framework established in Paul Krugman’s seminal 1998 paper.