A recent study conducted by a research team from Harvard University has shed light on the elevated concentrations of organofluorine found in U.S. municipal wastewater. The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, revealed that more than 60% of the organofluorine compounds detected in the samples were widely prescribed fluorinated pharmaceuticals. In contrast, federally regulated perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) made up less than 10% of the total extractable organofluorine present.

PFAS are synthetic chemicals known for their nonstick properties, commonly used in consumer products such as cookware, food packaging, waterproofing, and stain-resistant materials. Due to the strong carbon-fluorine bond present in these chemicals, they are notoriously difficult to degrade in the environment, earning them the nickname “forever chemicals.” The widespread contamination of soil and groundwater with PFAS has become a global concern, with traces even found in remote locations like the Tibetan plateau.

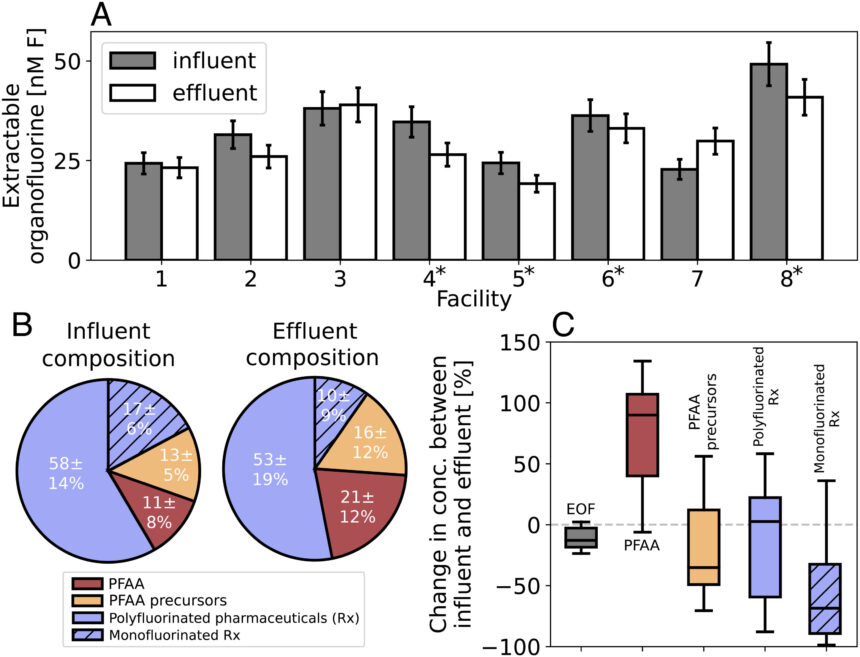

The study focused on eight large wastewater treatment facilities in the U.S. and analyzed organofluorine levels using bulk and targeted methods. The results showed that pharmaceuticals accounted for a significant portion of the measured organofluorine load, ranging from 62% to 75%. Despite advanced treatment processes, the removal rates of organofluorine did not exceed 24% at any of the facilities.

Of particular concern was the potential impact on downstream drinking water supplies for millions of Americans. The study estimated that over 20 million Americans could be at risk of consuming water with contamination levels above regulatory thresholds due to wastewater-derived PFAS. While the treated wastewater is not directly supplied to homes, it eventually mixes with other water sources and reenters the water supply cycle, posing a risk to public health.

The researchers highlighted the complex interconnectivity of water systems, emphasizing how treated wastewater undergoes multiple purification cycles before being reused. This process of water reuse can lead to the accumulation of contaminants like organofluorines, raising concerns about the long-term implications for human health.

In conclusion, the study underscores the urgent need for effective strategies to address organofluorine contamination in wastewater and protect drinking water sources. With millions of Americans potentially at risk of exposure to harmful chemicals, further research and regulatory measures are essential to safeguard public health and the environment.