Sleep schedules are often one of the first things that people choose to compromise in order to check everything off their to-do lists, especially with the end of the year approaching. But folks hoping for happy holidays should reconsider.

A new study from the University of Michigan shows that when people’s sleep cycles are misaligned with their internal clocks, or circadian rhythms, it can have drastic effects on their moods. Conversely, getting sleep when the body’s expecting it provides a potent boost to one’s emotional state and could alleviate symptoms associated with mood disorders, according to senior author Daniel Forger.

“This is not going to solve depression. We need to be very, very clear about that,” said Forger, professor in the Department of Mathematics and director of the Michigan Center for Applied and Interdisciplinary Mathematics. “But this is a key factor that we can actually control. We can’t control someone’s life events. We can’t control their relationships or their genetics. But what we can do is very carefully look at their individual sleep patterns and circadian rhythms to really see how that’s affecting their mood.”

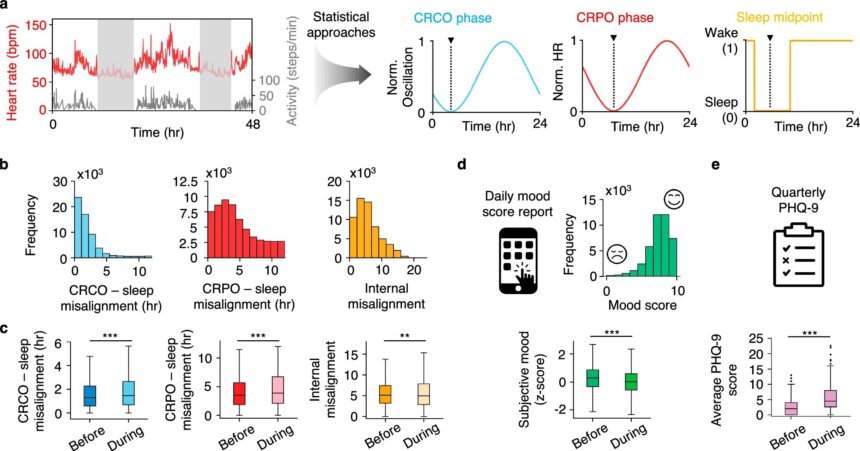

The research, published in npj Digital Medicine, delves into the real-world effects of sleep patterns on mood, using data from the Intern Health Study, which works with hundreds of first-year training physicians. The study analyzed the participants’ circadian rhythms, sleep cycles, and daily mood surveys to establish links between these factors and mental health.

The study found that when people’s sleep cycles were out of sync with their internal clocks, their mood was significantly affected. The researchers developed algorithms to assess Fitbit data and extract quantitative information about the participants’ circadian rhythms, sleep cycles, and alignment. The results showed a clear correlation between desynchronized rhythms and an increase in depressive symptoms.

The team identified three important patterns in the participants’ data: the central circadian clock, peripheral circadian clocks, and sleep cycles. They found that when the central circadian rhythm was out of sync with the participants’ sleep cycles, it had a negative impact on mood, particularly in cases of shift work. This misalignment was associated with poor sleep, appetite issues, and even suicidal thoughts.

By challenging prior assumptions about circadian disruptions, the study opens up new questions about how these disruptions manifest in different groups of people. The researchers are now looking to apply their methodology to students, older adults, and individuals with psychiatric disorders to further understand the impact of circadian rhythms on mental health.

Overall, the study highlights the importance of aligning sleep cycles with internal clocks to improve mood and mental well-being. By leveraging technology like wearable devices, individuals can better understand how their sleep patterns affect their mood and take steps to remedy any disruptions. This scalable approach could potentially help many people improve their mental health and well-being.